Most cookie banners are annoying and deceptive. This is not consent.

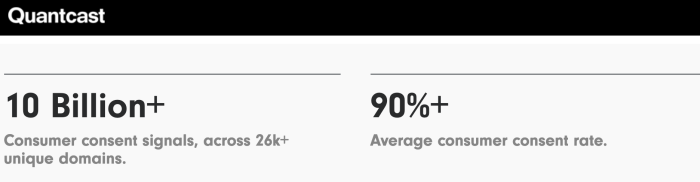

You're on your phone trying to check an article a friend has sent you, or quickly looking up info about an event that’s happening this weekend. And there it is: a gigantic cookie banner, a privacy notice that blocks your screen with a big, visible "ACCEPT" button. This is what the AdTech industry considers consent, and how companies like Quantcast end up claiming that their consent rate is over 90 percent. We think there something deeply wrong with that.

Nudging users to consent… Globally

Cookie banners exist because EU laws require websites and apps to ask users if they agree to most cookies and similar technologies (e.g. web beacons, Flash cookies, etc.) before the site starts to use them. (These rules are under reform and we’re fighting hard to ensure they include strong and better protections, despite opposition from companies.)

For consent to be valid, it must constitute a real meaningful indication of the individual's wishes and meet conditions such as being free, informed and specific.

However, that’s not how it often works in practice. Cookie banners are often provided by Consent Management Platforms (CMP), such as Quantcast or Oath, who are betting on the fact that you will never bother to look past the "I ACCEPT" or “OK” button. Only some CMPs allow publishers to decide if they want to show an equally big "I REFUSE" button to give their users a real choice. More often than not, the consent process is designed to be as opaque, unpractical and time-consuming as possible – just to make you click “ACCEPT”. So called “dark patterns”.

What few people know is that this “consent” is often interpreted as "Global Consent", a concept which assumes that if you accept being tracked on one website you “consent” to tracking across the web – as this “consent” is replicated throughout the supply chain. In practice this means that you “consent” to be tracked by hundreds of companies on hundreds or more of sites where they have a tracker. In the case of CMPs like Oath or Quantcast (where consent on one site may apply to other sites with global consent) this means that users accept tracking on hundreds of websites in a single click, often obtained out of users' frustration.

But let's pretend that you care, that you really don't want to be tracked and profiled by hundreds of companies that share, process and repurpose your data in ways that you wouldn’t expect or want. If you really care, be prepared to endure a terribly long and deceptive process, jump from one sub-menu to another, always with a big visible "ACCEPT" button in case this succession of screens discouraged you from make your will respected. A prime example for this behaviour is offered by Oath, which will take you to awfully wordy and poorly designed control pages only to redirect you to each of its partner-own dashboards.

Refusing tracking is already hard, opting-out completely is even harder. There’s currently no easy way to automatically block tracking on apps. The op-out services that tracking companies and advertising associations only apply to browsers and are usually based on – and this may sound ironic – opt-out cookies. To opt-out, you need to accept cookies, and you need to opt out for each browser on each device you’re using. If you delete your cookies, as is good security and privacy practice, you need to do it all over.

Needless is to say, we think that all of this fails to comply with the law, which among other things requires meaningful consent.

Deceptive and infringing practices

There are a few things which are inherently wrong with most Cookie Banners and Consent Management Platforms – including those that are based on the Transparency and Consent Framework of the IAB, an industry association for the online advertising ecosystem.

First of all, far too many CMPs and cookie banners come with pre-ticked boxes or are opt-out by default (you have to do something to opt-out). So if you're in a hurry or simply don't want to spend 10 minutes trying to dive into privacy policies, you will probably agree to have everything you do on the internet being shared with hundreds of companies, including the most intimate and personal sites you visit. Such pre-ticked boxes are clearly unlawful.

Secondly, we believe that many consent frameworks that are deliberately deceptive or misleading also don’t comply with GDPR. GDPR is clear that for consent to be valid, it must be informed, specific and freely given. If tracking involves special category data, such as when you use a health app, visit the website of a political party or that of a trade union, the bar is even higher. Your consent must also be explicit.

Finally, we are very concerned about the ways in which companies share, enrich and exchange your data in a vast ecosystem of data brokers and advertisers. Once you have given “consent”, your data disappears in the data brokerage ether and could be used for anything, from product promotion to microtargeting by political parties. As we argued when we complained to Data Protection Agencies against seven AdTech and data broker companies, that’s neither fair, nor transparent.

Privacy by design and by default

You should have the right to make real, informed choices and your consent is nothing that should be “managed”. Consent is something that can only be earned – ideally by those who clearly explain why they deserve your trust. That, however, puts a large part of the murky ad-tech ecosystem in an incredibly difficult position: hundreds of companies – most of them non-consumer facing – exchange, link and enrich data in ways that are so complex that it is incredibly difficult to do so transparently. Deceptive CMPs open the door to a broad range of abuses we observe in the AdTech ecosystem, from manipulation to discrimination. This, we believe, a systemic problem, that is inefficient, and puts everyone at risk. It’s bad for publishers and brands who care about their users, readers and consumers, as it betrays their trust.

So what’s the solution? Protecting your own privacy shouldn’t be a full-time job that requires advanced technical knowledge. That’s why we think that people and their data should be protected by design and by default (this is something the law requires too). It’s useful to compare good privacy to good food security: we don’t go into a restaurant and test whether our food is safe – we trust that there are laws, institutions and practices that ensure that it is. And when it isn’t, those you don’t play by the rules get punished. That’s something we want for our data as well.

What is Privacy International doing about it

Online advertising and invasive tracking everywhere need to be fixed and a first step is to make sure that the ecosystem is fully compliant with existing laws. That’s why in November 2018, Privacy International complained about seven companies, data brokers (Acxiom, Oracle), ad-tech companies (Criteo, Quantcast, Tapad), and credit referencing agencies (Equifax, Experian), with data protection authorities in France, Ireland, and the UK. Our submissions set out why these companies do not comply with the Data Protection Principles in GDPR, namely the principles of transparency, fairness, lawfulness, purpose limitation, data minimisation, and accuracy. They also do not have a legal basis for the way they use people's data, in breach of GDPR – as we’ve set out above, they don’t have valid consent. Many of these companies play an important role in Real Time Bidding (RTB). As a result of our submission to the Irish Data Protection Commission, the AdTech company Quantcast is now under investigation. The UK ICO is also looking more closely at AdTech. But we won’t stop here.