An unhealthy diet of targeted ads: an investigation into how the diet industry exploits our data

Companies selling diet programmes are using tests to lure users. Those tests encourage users to share sensitive personal data, including about their physical and mental health. But what happens to the data? We investigated to find out.

After re-testing the websites in September 2021 we found that:

- BetterMe is no longer sharing data (explicitly) with a third-party, as it was when we first analysed the site in March 2021.

- BetterMe now displays a new low weight warning when a user enters a weight under the World Health Organization's recommendations. However, the company doesn't prevent the user from continuing with that weight.

- BetterMe and VShred now display a cookie banner. BetterMe's banner allows users to reject tracking (effectively) while VShred banner does not allow users to reject tracking.

- More and more companies selling diet programmes are targeting internet users with online tests with little to no clarity when it comes to what happens to your data.

- These tests request sensitive personal data about your medical history and mental health.

- For at least two of the programmes we looked at, the data we entered did not affect the programme we were being sold, raising questions as to why the data is collected in the first place.

- We conducted traffic analysis to find out what happens to the data and discovered that one of them actively collected and shared sensitive personal data, while the poor security practices of the others meant the data was de facto accessible to third parties.

For many, browsing the internet or checking social media comes with its fair share of being targeted with ads selling “fad diet” subscription-based programmes, magic weight-loss powders, or promising a secret trick to lose weight quickly. Some of the products and programmes sold have been described as scams, with a very real impact for those suffering from eating disorders and those who fall prey to these ads. This is even more problematic due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which has seen the numbers of children with eating disorders “soar”.

Social media platforms have tried addressing the problem: Facebook has banned ‘"before-and-after" images or images that contain unexpected or unlikely results’; for users under 18, TikTok banned ads promoting fasting apps and weight-loss supplements; Instagram hides posts that promotes the use of certain weight-loss products from users under 18; and Twitter prevents advertisers from targeting people suffering from eating disorders. But there are workarounds. Facebook, for instance, still gives the option to advertisers to target teenagers with an ‘interest in extreme weight loss.’

As part of our research into the “AdTech” industry, Privacy International noticed that the diet ads we were targeted with led us to tests aimed at creating a so-called profile of our body and eating habits, to design a dieting programme, which they said were specific for our needs. Given our previous experience with depression tests and the current environment of vast and often unlawful data collection, Privacy International looked into those tests to find out what data those companies were collecting, what those programmes involved, where the data was going, and who it was shared with. Here is what we found.

‘Body profiling’: who are the companies trying to know you and what are they trying to sell?

For the purpose of this research, we have looked into three companies offering tests online to help you ‘find the diet that is best for you’: BetterMe Meal Plan, Noom and VShred. BetterMe Meal Plan and Noom were the first ads that came up on Google after a search for “weight loss,” while VShred targeted us with ads on YouTube following that search. It is worth noting however that some internet users are targeted by those very companies without ever searching for weight loss-related topics.

BetterMe Meal Plan

BetterMe Meal Plan is part of the BetterMe family of apps run by BetterMe Limited, a company registered in Cyprus. However, a look at the career section of their website reveals that they operate from Kyiv, Ukraine. They claim to have a team of over 100 people working for them and to be “one of the largest partners of Facebook/Google/Snapchat/Twitter from [Central and Eastern Europe].” BetterMe creates apps for healthy living: diet, walking, running, yoga, meditation, period tracker… They claim to have “50 million installs” across their apps and “6 million members across social media platforms”.

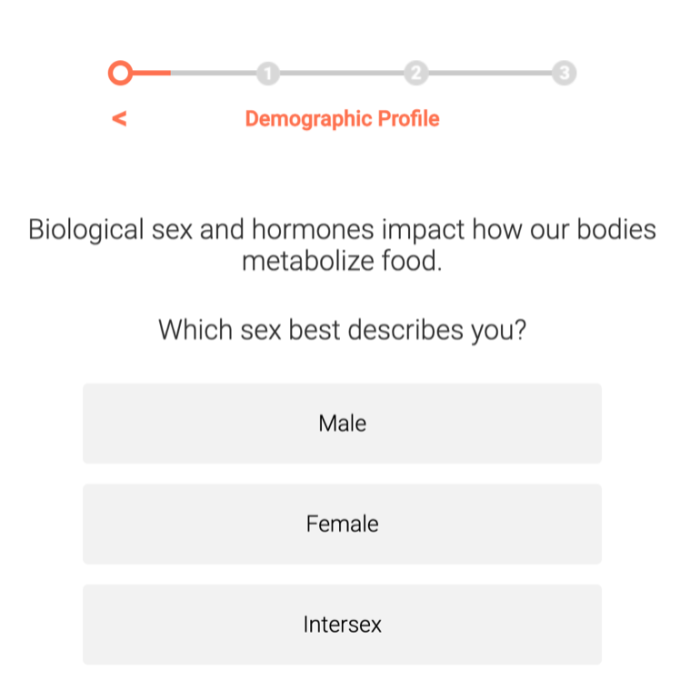

So we tried it out. BetterMe Meal plan starts by asking if you are a man or a woman. During our research, we observed that after this point, the questions will be identical no matter the gender you indicated, but the illustrations will change.

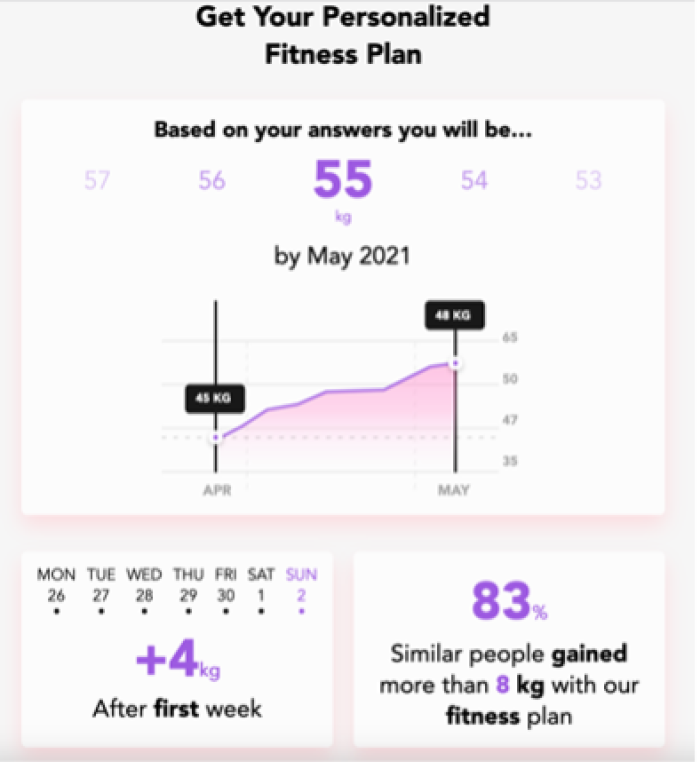

BetterMe Meal Plan then asks you to define your goal: losing weight, gaining muscle, or developing healthy habits. We’ve observed that even when your goal is not losing weight, the test will still ask you to define your ideal weight and provide you with the same weight loss plan whatever your ideal weight is.

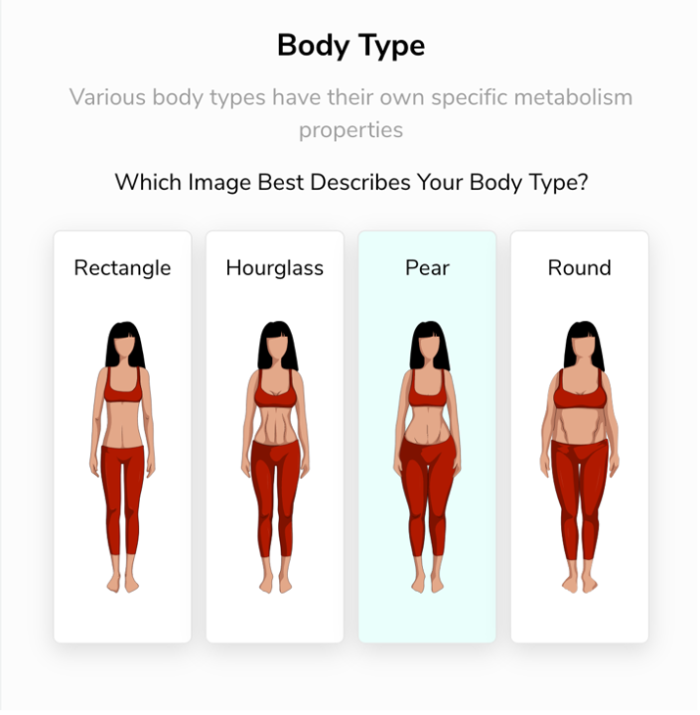

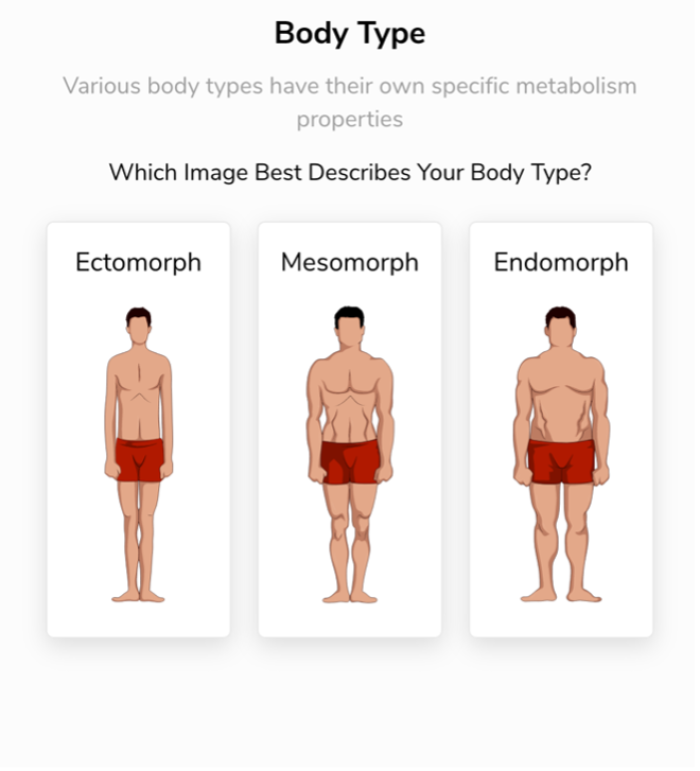

The test requires you to define your body type (‘rectangle,’ ‘hourglass,’ ‘pear’ and ‘round’ for women; ‘ectomorph,’ ‘mesomorph,’ and ‘endomorph’ for men) before going on to lifestyle questions: what does your typical day looks like (at the office, taking long walks, doing physical work…), when were you last at your ‘ideal weight,’ what your ‘bad habits’ are (not getting enough sleep, eating late at night, eating too much sweet or salt, soft drinks…), how much do you exercise, what are your energy levels like, how much do you sleep, how much water do you drink, what kind of food you enjoy eating…

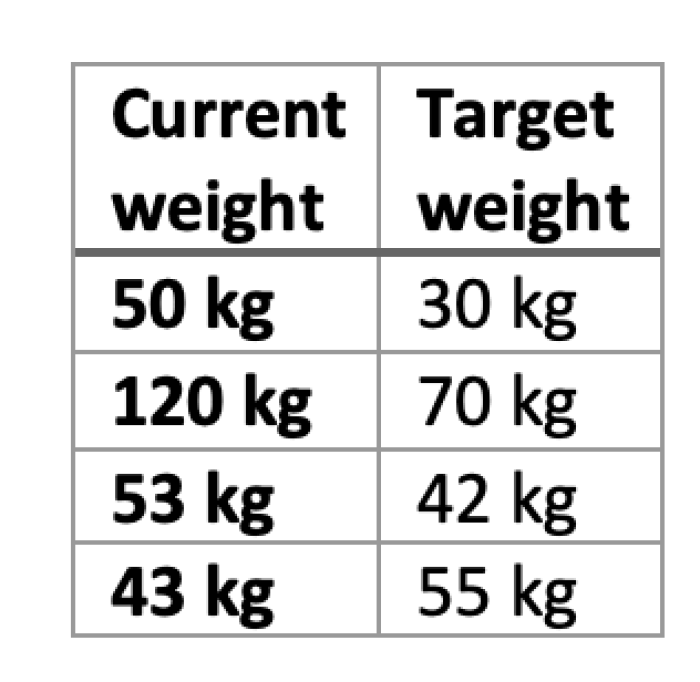

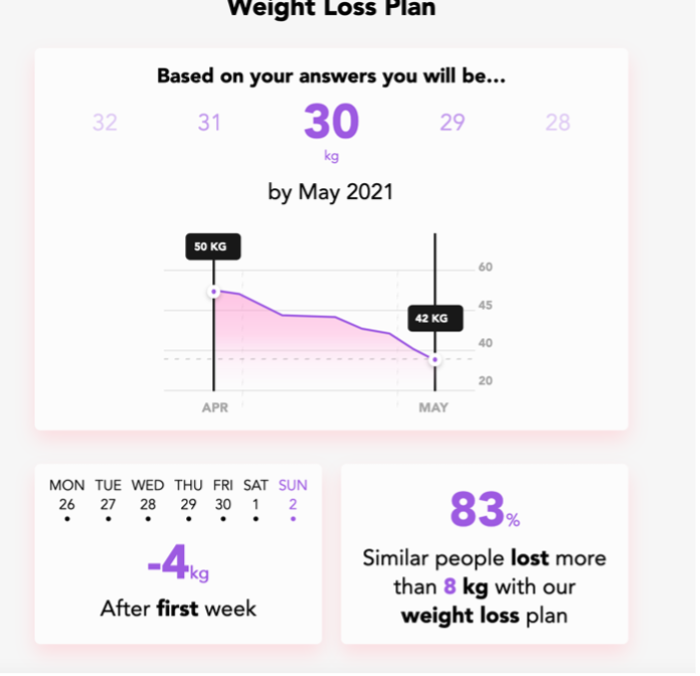

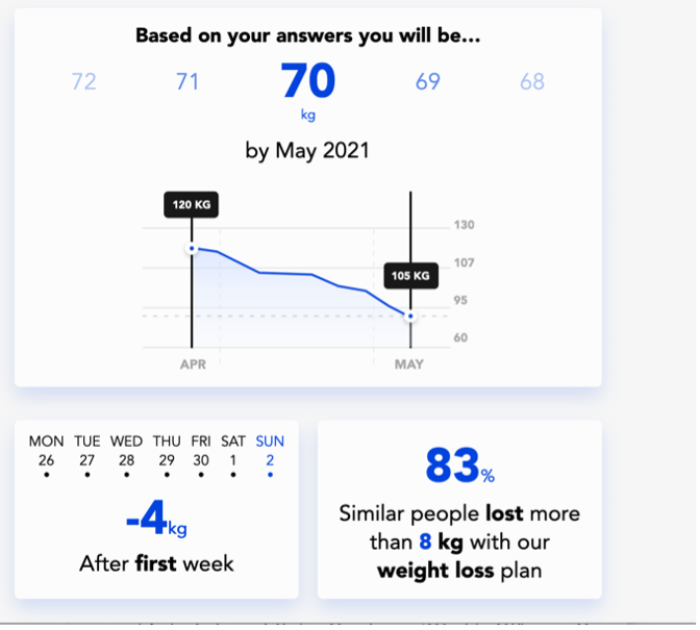

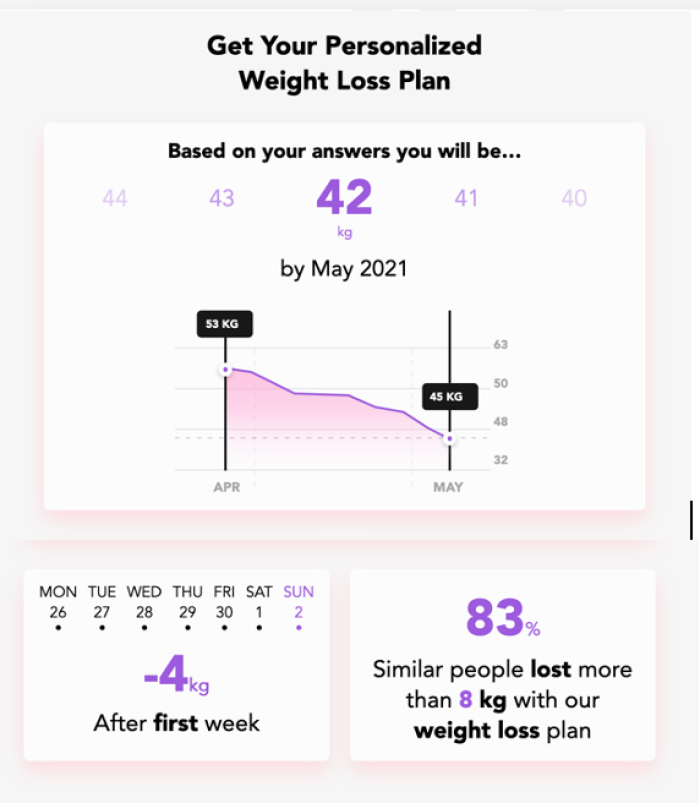

The last round of questions pertains to measurement: age, height, weight and target weight. Regardless of the target weight you enter, BetterMe Meal Plan will have a ‘plan’ for you. That means even when you enter a completely unrealistic weight target like 30 kilos for 160cm (i.e. a weight target that would kill you), you are presented with a ‘plan’.

September 2021 update: BetterMe now display a new low weight warning when a user enters a weight under the World Health Organization’s recommendations. However it doesn’t prevent the user from continuing with that weight.

Except our research shows that the plan is always the same regardless of the data you enter. The only things that change are your current weight and the target weight you have entered. Here is a table with some of the values we tested:

In all instances, BetterMe Meal Plan promised us we would reach our target weight within a month, and that we would have lost (or gained) 4 kg after the first week. For every profile they claim that 83% ‘similar people’ lost (or gained) more than 8kg with their weight loss plan. The promised plan costs between $1.7 to $5 per week depending on the subscription and promises ‘professional analysis of your nutritional needs’, recipes, ‘fat-burning workouts targeting your problem zones’, shopping list, daily tips and ‘24/7 support from our team of fitness coaches’.

Following the research done for this report some changes have happened. In a response to this report BetterMe said: “The current version alerts users if they indicate a target weight lower than recommended by World Health Organization. We are also developing a feature that would not let users that enter a weight/height ratio lower certain level to finish the onboarding.” Read their full response in the side banner.

Data collected by BetterMe Meal Plan:

- Goal (weight loss/muscle gain/healthy habits)

- Demographics

- Age

- Gender

- Weight related questions

- Height/weight

- Ideal weight

- When were you at your ideal weight?

- What’s your body type?

- Lifestyle

- What’s your typical day like? (at home, at work, physical work)

- What are your habits? (eating late at night, drinking soft drinks, eating salty food…)

- How physically active are you?

- What’s your energy level like?

- How much do you sleep?

- How much water do you drink?

- What vegetables do you like to eat?

- What vegetarian protein do you like to eat?

- What meat do you like to eat?

- Behaviour

- Do You Relate to the Statement: "I often require external motivation to keep going. I can easily give up when I feel stressed”

- Do You Relate to the Statement Below: "I’m afraid I won’t have time to do the other things I love because I’ll be so busy exercising and planning meals"

Noom

Noom is a US-based company that sells weight-loss and healthy living apps. They pride themselves in having their Diabetes Prevention Program recognised by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and being mentioned in academic publications. In 2021, the company raised $540 million in investment funding.

Noom starts by asking you if you are here to ‘get fit’ or ‘lose weight’, however the questions we were asked were the same in both selections. And even when we chose ‘get fit,’ we were still required to enter a target weight.

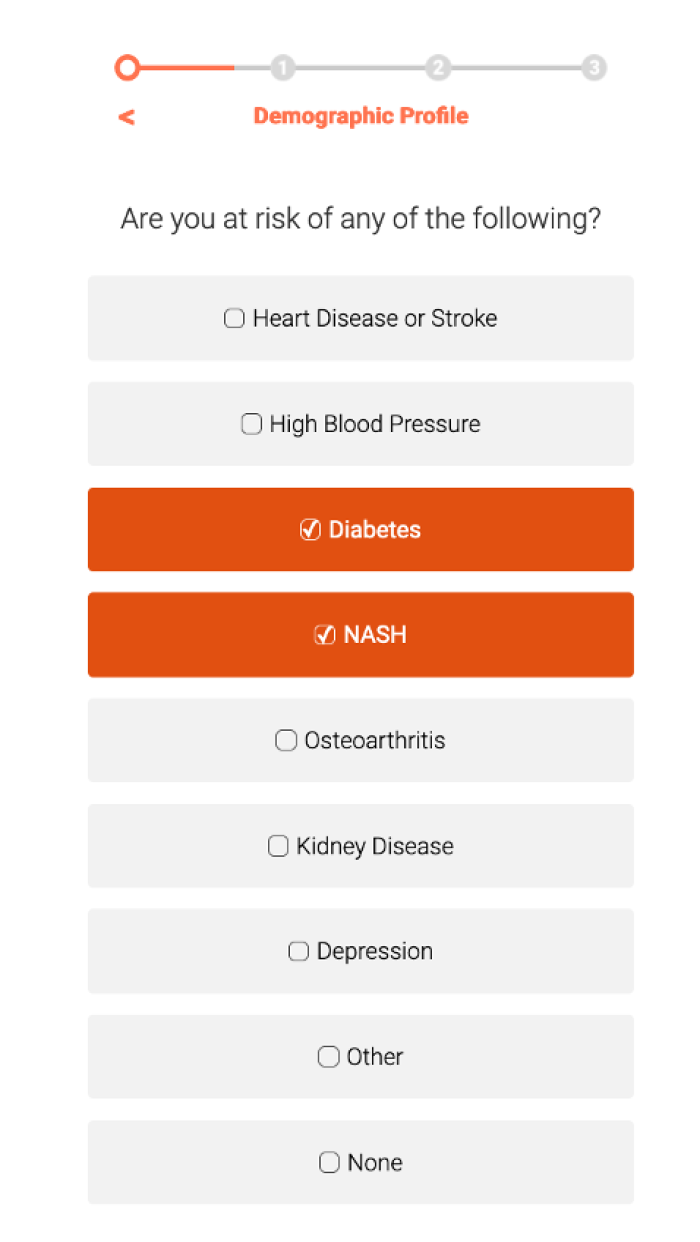

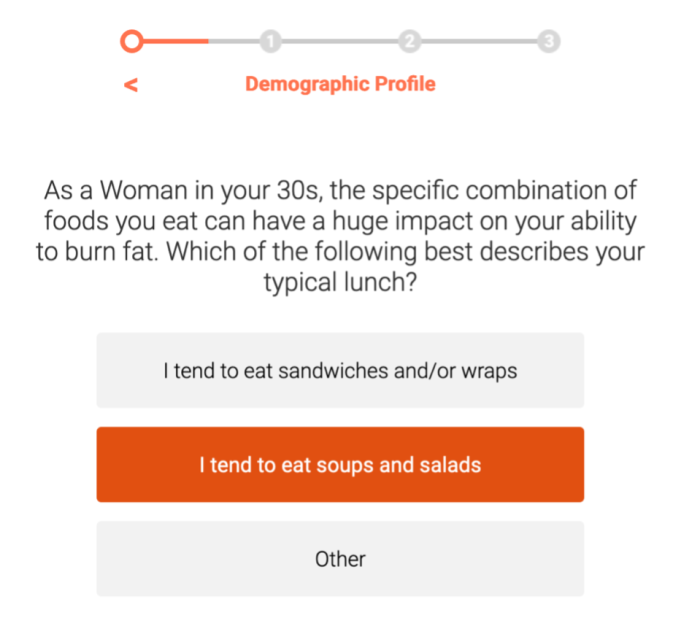

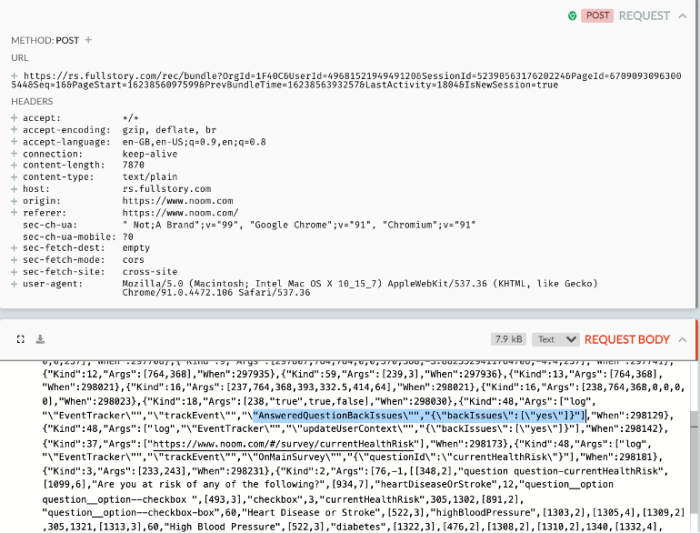

However, it is worth nothing that Noom does not allow you to set a target weight below an average BMI index. You are then asked to enter your gender, whether you are pregnant, your age range, how healthy you generally are, what you tend to eat, how often and whether you have back issues. As part of the demographic profile, you are also asked if you are at risk of the following diseases: heart disease/stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis), osteoarthritis, kidney disease, depression or others.

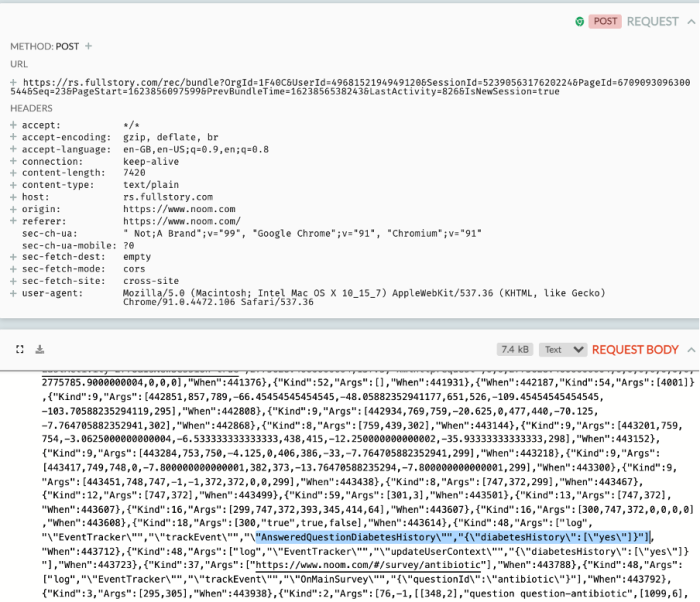

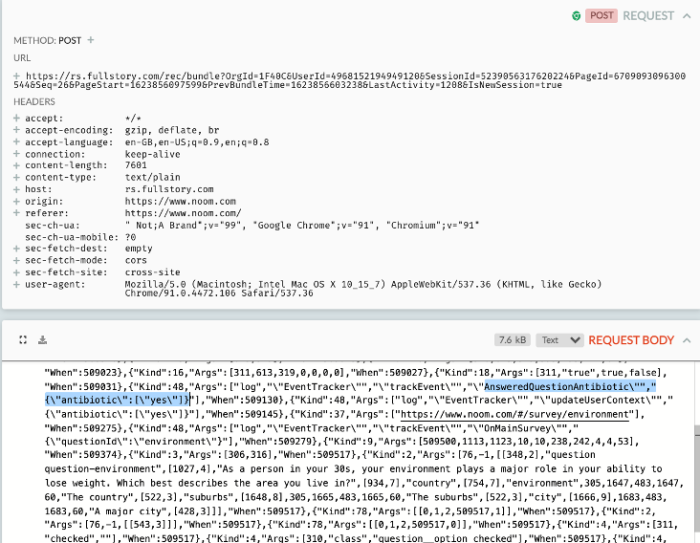

From our research, regardless of your response you are then asked if you have every been diagnosed or received treatment for diabetes. You are also asked if you have taken antibiotics in the past two years. We consider that answers to most of these questions can be considered health data, and therefore sensitive personal data under data protection frameworks like the GDPR (see Article 9) in the European Union. This means that Noom would be legally obliged under EU and UK data protection law to prove that they have taken extra steps to specifically protect these categories of data.

At the end of the Demographic Profile, Noom asks about the kind of environment you live in (city or countryside). The next step is entering an email address. You are asked to “Enter an email address to see how much weight you can lose for good with Noom.”

A graph then appears, describing your weight loss plan towards your planned goal.

The second part of the test focuses on “customising your plan” – and you are asked more questions.

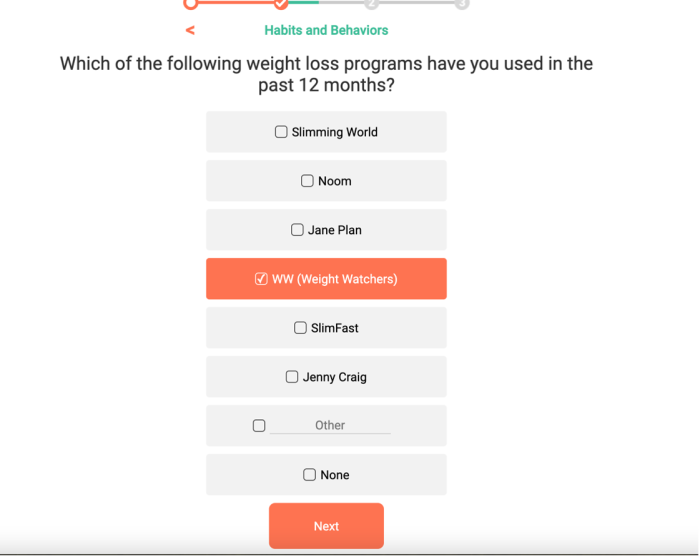

You are asked about life events that have affected your weight loss (including stress and mental health), how long were you last at your ideal weight, which weight loss programme you have used in the past (featuring the names of specific brands like Weight Watchers), what you have attempted to lose weight…

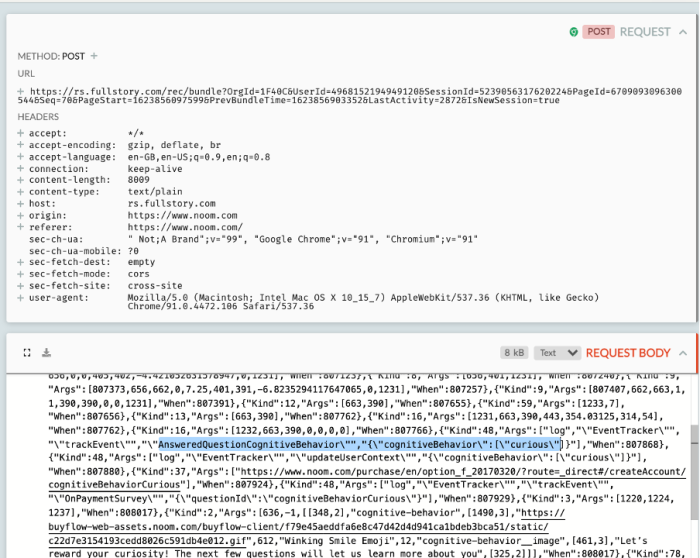

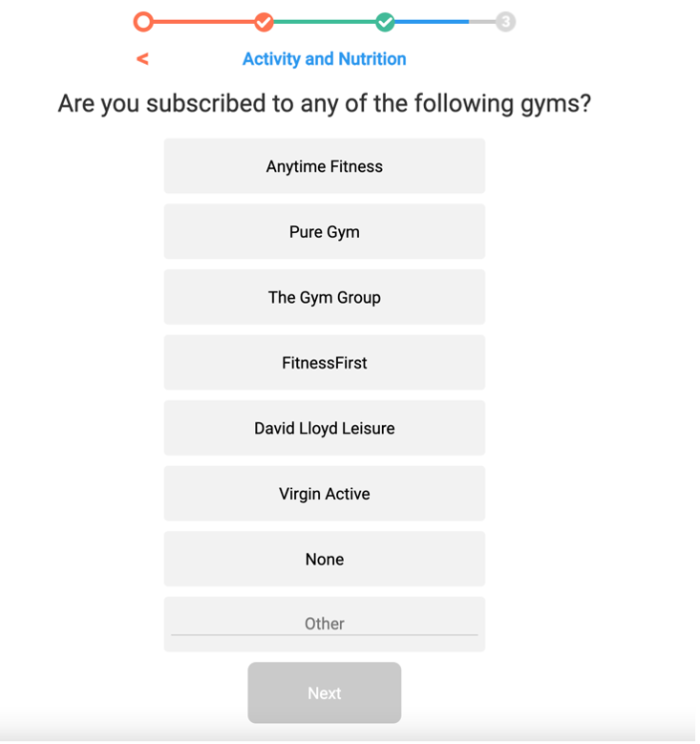

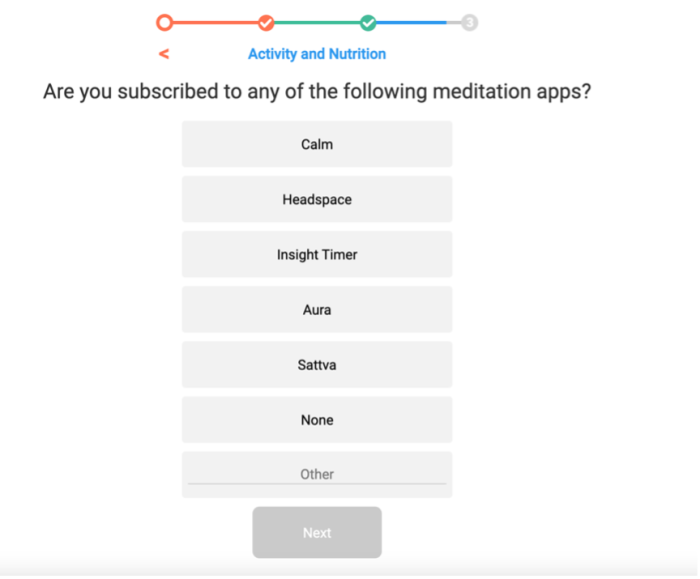

And finally, you are asked even more questions. The last part “activity and nutrition” asks about what you want your diet to focus on, if you have physical activity limitations, dietary restrictions and food allergies, how you feel about Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, your motivation for weight loss, your feelings about it, what time do you have an urge to snack, what triggers it, if you have any subscription to things like meditation app or gym membership and if so what the brands are, how busy you are, if you cook for meals… etc.

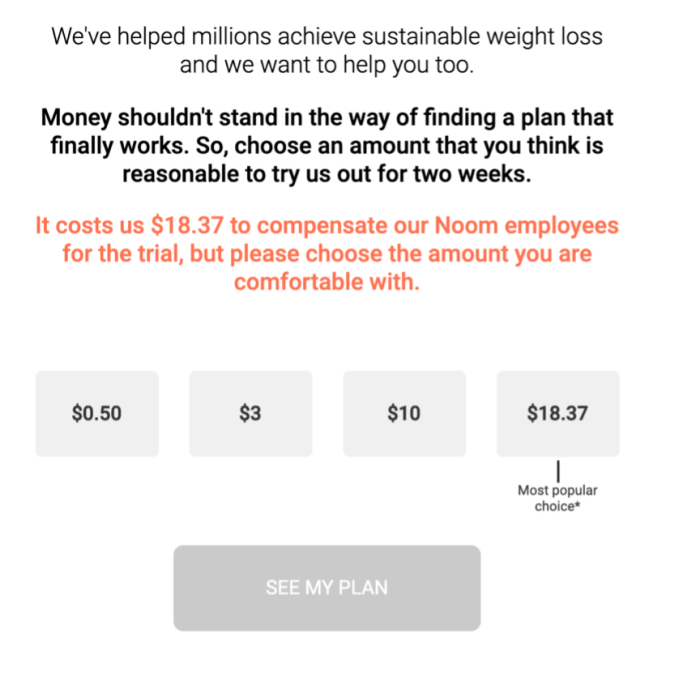

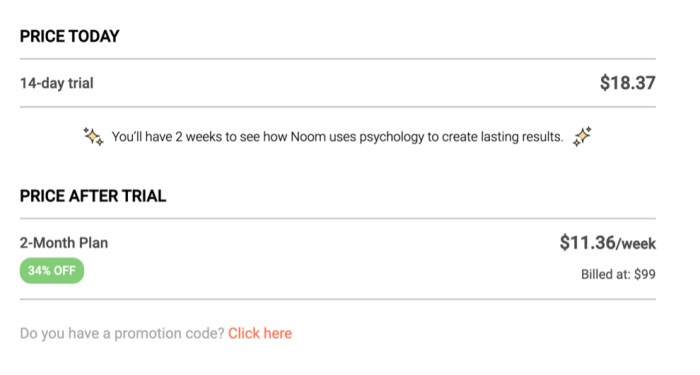

Noom then asks you how much you want to pay for the plan… for the first two weeks. In our research, they recommended $18.37 but they gave us the option to go as low as $0.50. We also received an email from Noom offering us a free trial. After the two weeks trial, Noom signs you up to a 2-month plan billed at $99 for two months.

Data collected by Noom:

- Goal (weight loss/fitness)

- Demographics

- Gender

- Age

- Do you live in a city or in the countryside?

- Weight-related questions

- Size and weight

- Ideal weight

- How long since you were at your ideal weight?

- How fast do you want to lose weight?

- What other goal do you want to achieve (running a 5k, feeling healthier…)?

- Lifestyle

- Do you need to make a lot of changes to improve your lifestyle?

- How often do you eat?

- Preferred food

- How busy are you?

- How do you prepare your meal?

- Do you eat at roughly the same time for each meal everyday?

- At work, are you typically on your feet or sitting at a desk for most of the day?

- Health

- Back issues

- Pregnancy status

- Disease you may be at risk of

- Have you been on a treatment for diabetes?

- Have you taken antibiotics?

- Do you have physical limitations?

- Do you have dietary restrictions or food allergies?

- Is there a history of diabetes in your family?

- Behaviour

- Have there been life events that have affected your weight?

- Do you relate to the statement: “I know what I should be doing to lose weight, but I need a way to do it that fits into MY life.”

- Has your weight ever affected your ability to socialize or engage with friends and family?

- Do you relate to the statement: “I need some outside motivation. When I am feeling overwhelmed, it can be easy to give up.”

- Do you relate to the statement: “I have been thinking about weight loss for a while, but life is so busy I find myself putting convenience first.”

- What do you want to focus on (nutrition, physical habits…)?

- How do you feel about cognitive behaviour therapy?

- How has your motivation about weight loss evolved?

- How motivated are you about weight loss at the moment?

- When it comes to your weight loss goal, what’s on your mind? (taking care of myself, I have a specific goal, I’m looking for something new)

- When do you feel an urge to snack?

- What triggers your urge to snack?

- Do you relate to the statement: “Food often provides me emotional comfort.”

- Do you relate to the statement: “I’ve been able to eat healthier or exercise for a week or two but then I fall back to my old habits.”

- Do you relate to the statement: “The people around me can make it difficult to maintain healthier habits.”

- Do you relate to the statement: “I am usually multitasking while I eat (like watching tv or scrolling on my phone).”

- Do you relate to the statement: “I usually clear my plate even if I’m already feeling full.”

- Do you relate to the statement: “I have felt like a failure because of one unhealthy decision. This often leads me to make even more unhealthy decisions.

- Other than weight loss what else do you want to explore?

- Private companies that you use

- Which weight loss programmes have you used?

- What methods have you attempted in the past?

- What services are you currently subscribed to (gym, meditation apps, fitness apps…)

- What gym are you subscribed to?

- What fitness app are you subscribed to?

- What meal delivery kit are you subscribed to?

- What meditation app are you subscribed to?

- How did your hear about Noom?

- What is your email address?

VShred

VShred is a US-based company that sells weight-loss programmes, food supplements, and sports clothing.

Like BetterMe MealPlan, VShred starts by asking if you are a man or a woman, and just like them the questions you are asked are the same regardless of your gender, only the illustrations change. You are then asked about age, height, weight, how active you are and to describe your goal.

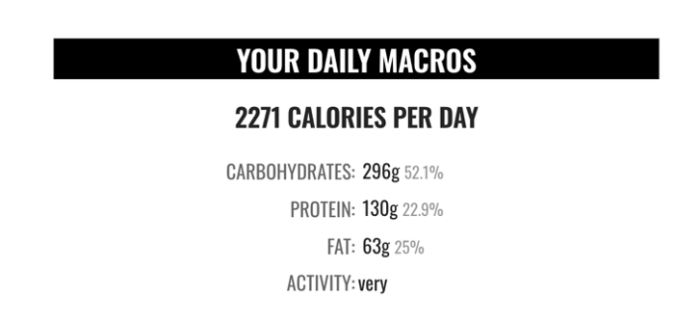

Based on the answers you provided, VShred provides you with your ‘Daily Macros,’ the number of calories, carbohydrate, protein and fat you’re ‘allowed’ and your level of activity.

Beyond the so-called Daily Macros, in our research the content that Vshred offered was exactly the same regardless of the data you enter. A set of books and digital content sold for $57.

The only apparent change? Entering “man” will give you books with pictures of male bodies on the front cover, while entering “woman” will give you books with pictures of female bodies on the front cover and you will see the term weight-lifting replaced with fitness. And of course it’s pink for women and blue for men.

Data collected by VShred:

- Demographics

- Age

- Gender

- Weight related questions

- Height/weight

- Ideal weight

- What’s your body type?

- Lifestyle

- How physically active are you?

So… What happens to my data?

In the first part of this report, we have showed you what data diet companies are collecting, and we have also showed you that not very much seems to happen based on the data you enter, as the programme you are being sold appears to be always the same. Online test asking your data and not making any use of it… that’s a bad sign.

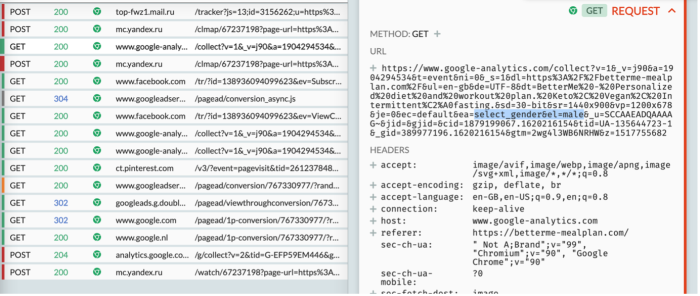

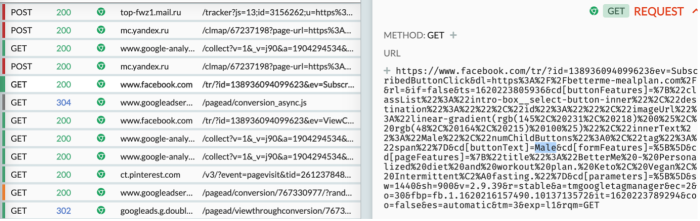

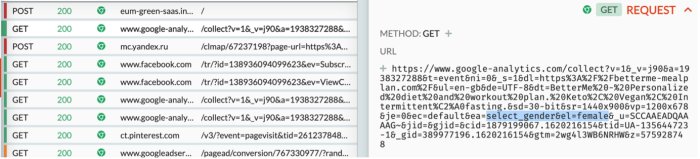

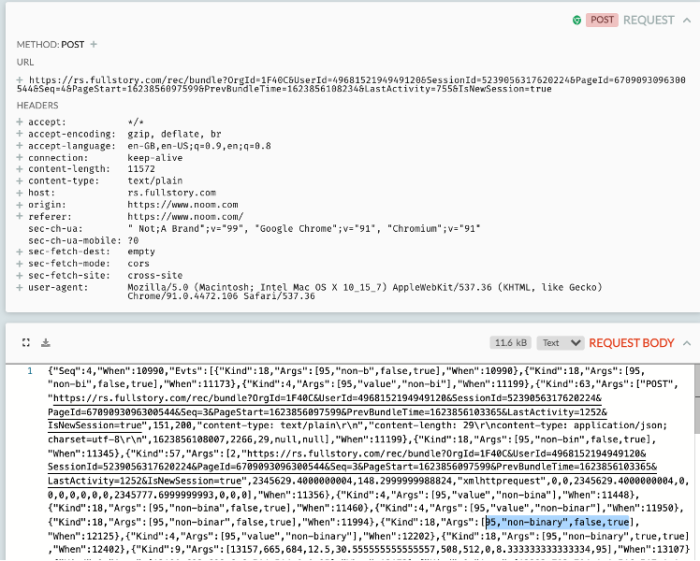

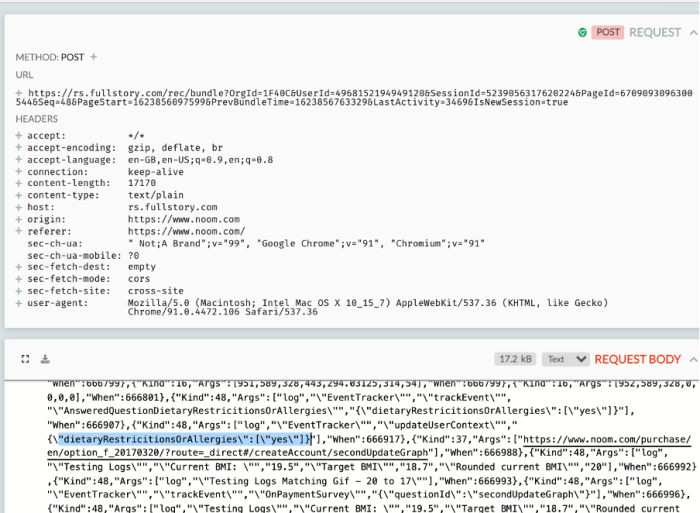

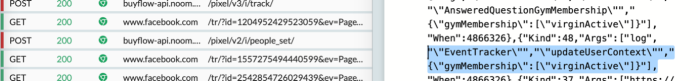

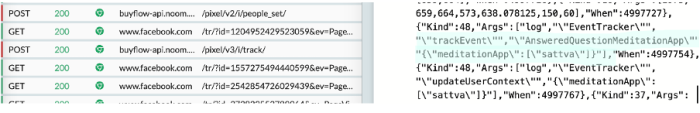

So, we wanted to find out what actually happens to this data. In order to do this, we have used the open-source HTTP toolkit to intercept HTTP(S) requests and explore and examine traffic between the websites we identified and third parties. We also analysed their privacy policies to compare them with what we had found from the traffic analysis.

The analysis consisted of the following steps:

- Open HTTP toolkit and launch the embedded version of Google Chrome. The interception starts automatically. If this version of Google Chrome has been used previously, clean any cookie, cache, data to ensure a clean state

- Open the selected website

- Answer test questions

- Look at the requests, which are collected by HTTP toolkit in the view section

- Use the HTTP toolkit search to search for relevant keywords (i.e. female, weight loss, number of kilos and size entered, diabetes…)

It is worth noting that our research only scrapes the surface of how the collected data may be used by diet companies. This methodology enables us to look at what happens between the browser on one side (what the user uses to access a website, in this case Google Chrome) and the website visited or third parties on the other.

Data that is exchanged directly between the website and the third parties are not publicly accessible but could be another avenue for data sharing. For example, sites could be selling bulk data to interested third parties without informing users.

With that in mind, here is what we found…

BetterMe Meal Plan

When looking at the traffic between the browser (us) and BetterMe’s website, BetterMe did not appear to be sharing data with third parties. Interestingly, while the URL on our browser never changed and remained at all times the same (i.e., https://betterme-mealplan.com/), every time we provided an answer a GET request was sent back to a variety of third parties such as Google Analytics, Facebook and Yandex (what we refer to as a request in this study is a basic message exchanged between our computer and a server. It can include different information ranging from the browser and device we are using and the page we are currently viewing to more complex elements such as a font). In one instance, this request included our gender (male or female), this information being therefore shared with Facebook and Google. Looking at the website code, we can see that the gender is coded as a value of a data-gender field. Interestingly, none of the other questions display a similar field (say data-body-type) which would logically be used to collect this information. From here there are two explanations to this behaviour. Either BetterMe Meal Plan wanted to share the gender of the user with Facebook and Google and added this field on purpose, using a different, more visible, method to collect and process the data provided by the user. Or they actually only collect and process this one information and are inadvertently sharing it with Facebook and Google (a behaviour we encountered in the past with websites offering depression tests and inadvertently sharing answers with third parties). Given that the results of the test never change no matter what information the user provides, it’s indeed possible that the entire test doesn’t actually do anything apart from making you feel like you’ll get an individually tailored meal plan.

September 2021 update: BetterMe is no longer sharing data (explicitly) with a third-party, as it was when we first analysed the site in March 2021.

In response to our report, BetterMe explained: “The answers from the web onboarding are collected into our database (hosted on servers of our cloud service provider) and are processed, in particular, to provide our services, to suggest daily calorie intake suitable for you or provide you with a vegetarian meal plan if you exclude meat from your food preferences. Therefore, the final product that the customer receives depends on this data.” Read their full response in the side banner.

In their Privacy Policy, BetterMe Meal Plan provide explicit information on their sharing practices with third parties. They name some third parties and disclose why they are sharing the data with them at the top: “For improving the app and attracting users, we use third party solutions. As a result, we may process data using solutions developed by Amplitude, Facebook, Firebase, Google, Apple, Appsflyer, Crashlytics. Therefore, some of the data is stored and processed on servers of such third parties. This enables us to (1) analyze different interactions (how often users make subscriptions, the average weight and height of our users, how many users chose a particular area for improvement); (2) serve ads (and are able to show them only to a particular group of users, for example, to subscribers).”

However, section 4 of their privacy policy purports to allow them to share data with unnamed service providers (“marketing partners”, “measurement partners”). It is also worth noting that they rely on their “legitimate interests” as a lawful basis for data collection and processing, including for marketing communications (in addition to “consent”), analytics, sending push notifications… as it seems, practices for which the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations and the GDPR generally require opt-in consent.

Despite BetterMe Meal Plan collecting health data, which are considered sensitive personal data under the GDPR, it seems no system is currently in place to request explicit consent or treat this data with the additional safeguards required by the GDPR.

Noom

Of the three diet programmes we have reviewed, Noom is the one with the most to ask… and the most to share.

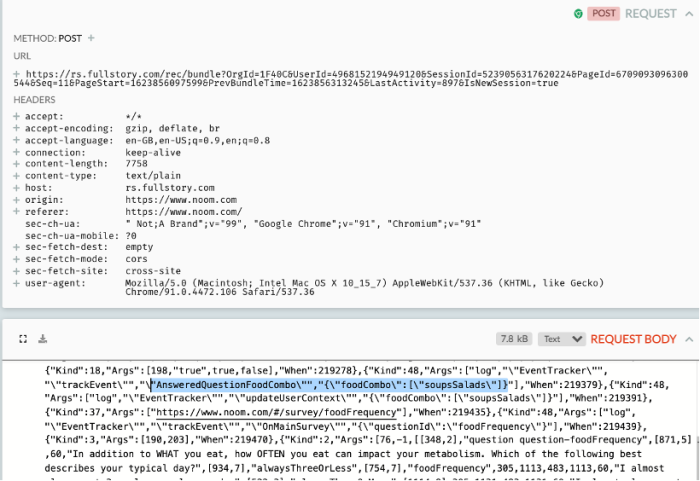

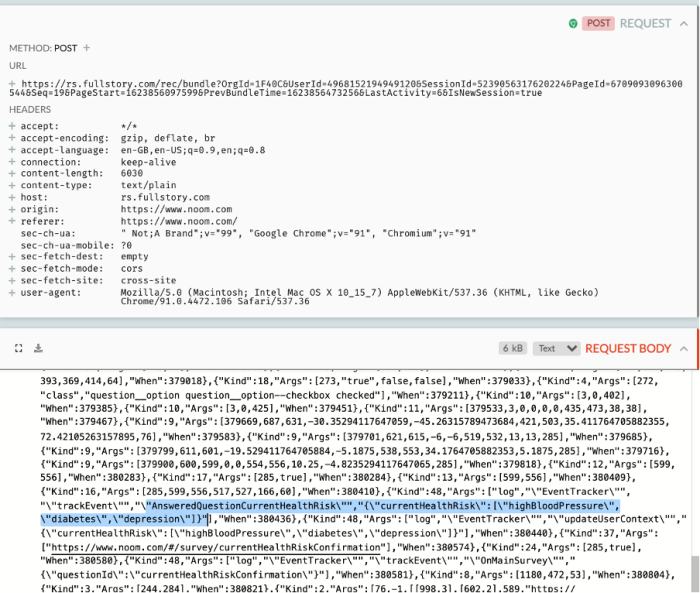

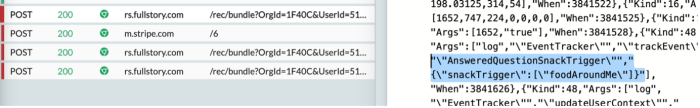

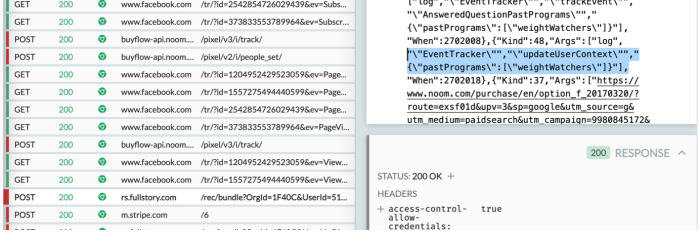

As we highlighted in the first part, Noom asks a lot of questions about your health: medical history, whether you have been taking antibiotics, whether there have been occurrences of certain diseases like diabetes in your family… Noom does not keep all this information for itself. It is being shared with a company called FullStory.

FullStory is a platform that allows companies to understand how consumers interact with their website: what they are looking at, what they are clicking on, what bugs or issues they may be experiencing, what they are purchasing, etc.

FullStory claims to have the capacity to exclude sensitive personal data from being captured, yet Noom appears to share its users’ health data with FullStory. Every single data point we entered was being shared with FullStory. For instance, when we are asked to enter our gender, upon inputting “intersex,” we are asked to indicate how we define ourselves. We entered “non-binary” – this very information was shared with FullStory in a POST request, therefore in a deliberate manner,in the sense that Noom apparently actively decided to send this information to FullStory. This was not done inadvertently as might be the case with BetterMe Meal Plan or some depression test websites we tested in the past. Even if, as they claim, FullStory excludes sensitive information from the data they process, Noom shouldn’t be sharing this data in the first place. The decision to actively share this data without users’ knowledge nor consent is problematic in its own right.

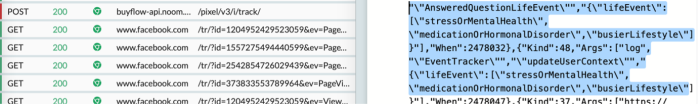

Those lifestyle questions also offered answers that could lead a user to share further sensitive medical information. For instance, when asked about what may have triggered our weight gain, Noom gave us the option to provide answers like “Stress or Mental Health” and “Medication or Hormonal Disorder,” which were shared with Fullstory.

Before we even signed up to their subscription plan, Noom was therefore able to build an extremely thorough and intimate profile of us, our mood, mental health, eating habits, health history, consumer habits… And all of this was shared with FullStory, a third party, without informing the users or requesting their consent. Indeed, no request for consent was made and FullStory is not mentioned in Noom’s privacy policy. Some Noom users have taken issue with this and filed a claim against Noom and FullStory in the US, arguing amongst others that users are never informed about data sharing with FullStory. The claim was dismissed, although the question of the suitability of Noom’s privacy policy in this regard was not resolved.

Halfway through the test, Noom asked us to share an email address, thus allowing them to build a unique profile of us. A look at their privacy policy suggests that they combine demographic data with personal data: “To the extent that Noom combines any non-personally identifiable Demographic Information with User’s Personal Information that Noom collects directly from User on the Website and the Mobile App, Noom will treat the combined data as Personal Information under this Privacy Policy.” This could mean they may potentially categorise users in an undisclosed way, for their own analytics.

Further down the privacy policy, the wording sounds a lot like they may be sharing personal data with data brokers: “Noom may share your Personal Information with various business partners. Some of these business partners may use your personal information to facilitate the offering of services or products that may be of interest to you.” We have previously highlighted the harms caused by the data broker ecosystem – feeding it with sensitive health and lifestyle data can only exacerbate these.

While Noom’s privacy policy purports to give it free rein to share data with any third parties, it is not providing any explicit or specific information about who these third parties are, what data is actually being shared, and when. And at no point are we, as a user, asked to provide consent to this sharing.

Finally, Noom does not simply share your data with third parties, their privacy policy also says they may get more data about you from other third parties, and combine it with the data you provide through your use of Noom’s services: “Noom may, from time to time, supplement the information Noom collects directly from User at the Website, Mobile App and through Services with outside records from third parties for various purposes, including to enhance Noom’s ability to serve User, to tailor Noom’s content to User and to offer User opportunities that may be of interest to User.”

VShred

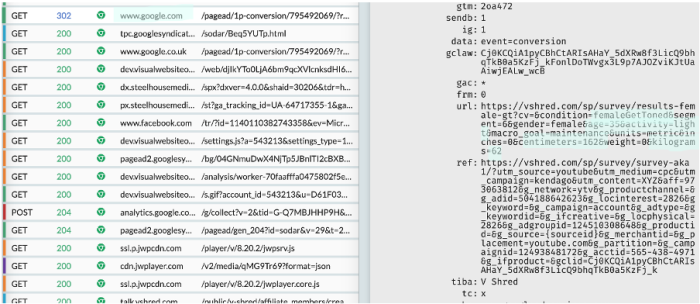

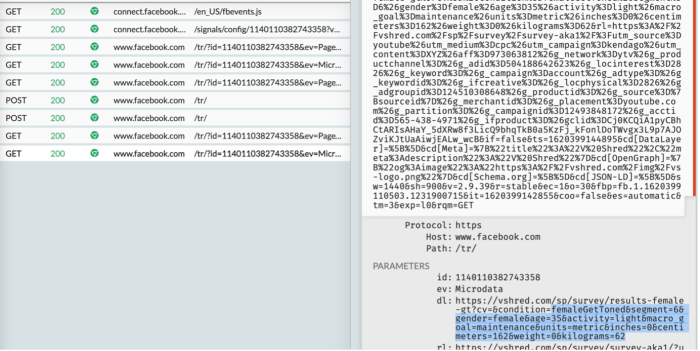

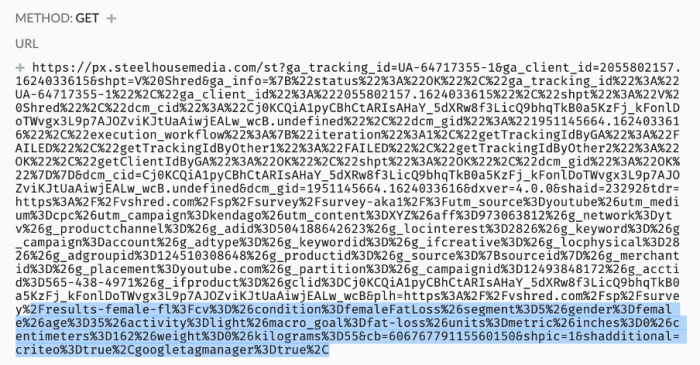

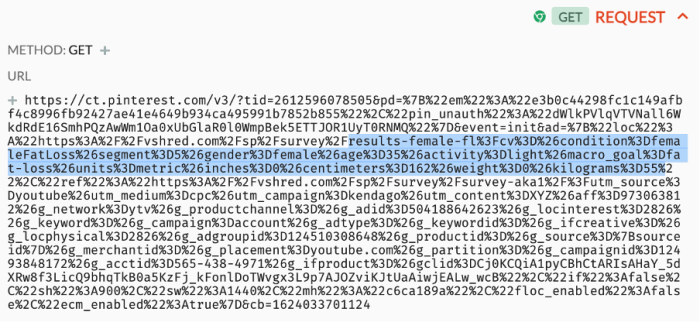

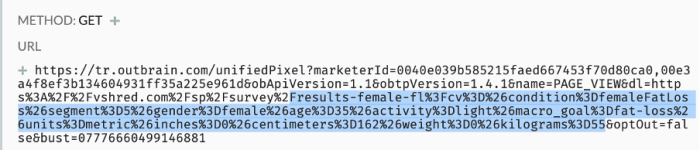

VShred did not quite collect and share as much information as Noom, yet it failed its users’ privacy in a different way. The data we entered into their survey appeared in the URL, as we were taking the test. For instance, the URL after taking the test was:

We see the data we entered appeared: female, fat loss (the objective we had entered), age 35, moderate activity level, height 164cm and weight 63 kg.

Similar to what we described with BetterMe Meal Plan, this is problematic because you are not the only one seeing the URL. When you visit a website that embeds trackers and third parties, these services will usually get access to the URL of the site you are visiting. This will either happen through the referrer URL, a parameter in the HTTP request that indicates what page the user is viewing, or through other parameters. It’s worth noting that some browsers have changed their default behaviour and while, in the past, all third parties would have access to the complete URL, most modern browsers will now only transmit the main domain (vshred.com instead of vshred.com/?gender=female).

For instance, on this picture we see Google having access to the following data: female, “get toned” and “maintenance” (the objectives entered), age 35, light activity level, height 162 cm and weight 62 kg.

In their privacy policy, VShred say from the get-go that European privacy laws will not apply to their data processing: “V Shred is located in the United States. Information collected on our website and applications is stored in the United States; therefore, your information may become subject to U.S. law. By using VShred.com and the V Shred platform(s), including social media, you consent to the transfer of your data overseas and across borders, and from your country or jurisdiction to other countries or jurisdictions around the world. The laws governing data in your home country may differ from those in the countries to which data is transferred. By accessing and using our website and mobile applications, you consent to the transfer of your data in this manner.”

We are puzzled – to say the least – by this statement considering our member of staff who conducted the research, based in Europe and using a European IP address, was targeted with advertisement from VShred. European privacy laws are quite clear that if you offer services to individuals in the European Union (irrespective of whether payment is required for these services), European privacy laws apply.

These laws most often require information and consent for such data sharing practices. Yet we were never asked to provide consent before sharing our data, despite the pretty sensitive nature of the information collected and shared. Indeed, they say that they “will also use this precise geolocation information for analytics purposes and will share your precise geolocation information with certain third parties, including, but not limited to, dealers and parties who provide targeted advertising and analytics services.” They also add: “We share the information you provide with affiliates, subsidiaries, SculptNation, LLC, sales representatives or authorized dealers in your area, other business partners, and third party marketing partners. They may use your information to communicate with you about their products and services, and to send you further notices, promotions, solicitations, or brochures, and other marketing materials regarding our website, our products, and the services they provide.”

Conclusion: it’s time for fad-diet ads to fade away

With the numbers of eating disorders on the rise, it is time we listen to the demands of organisations working on these issues and bring an end to the relentless targeting of internet users with ads perpetuating myths around diets and perfect bodies. As consumer organisations and healthcare services warn against the risks of fad diets, and online ads in particular, we need to acknowledge those companies take advantage of our society’s obsession with thin bodies not only to sell dubious products that can constitute a genuine public health risk, but also in some cases to exploit our data.

Under the pretence of finding the best diet for us and protecting our health, fad-diet companies are only collecting more and more data about us, without providing us proper information about what happens with the data and who they share it with.

In doing so, they promote unrealistic expectations of what bodies should look like, what dieting implies and perpetuate binary and sexist perception of gender norms, where women (in pink!) ought to have thin, lean bodies, while men (in blue!) should be bulky.

What we now know is that the data you share with them does not stay between you and those companies. Either because of poor technical insight, or because they are actively sharing it with third parties, your data ends up in the hands of large platforms and other marketing companies. And they usually do so without telling you – at no point in our journey with these sites did we see a cookie banner, pop-up or statement that would notify you of your activity being tracked and information being shared in this way – and without obtaining your consent to the sharing of your sensitive data.

September 2021 update: BetterMe now displays a cookie banner which allow users to refuse tracking, drastically reducing the amount of third-party trackers loaded. VShred now also shows a cookie banner but doesn't offer any option to decline tracking.

While it is difficult to assess based on these companies’ privacy policies what actually and specifically happens to our data as we take the tests (as opposed to what happens after subscribing to these apps), the privacy policies we have read provide scope for worrying practices. We have therefore filed Data Subject Access Requests with each of those companies, in the hope of obtaining further clarity. We may publish a follow-up piece to describe what we find.

Because no such report would be complete without mentioning Big Tech’s role in all this – big tech companies generate revenue from these ads. When content is sensational, such as content promising huge weight-loss results, magically, overnight, the companies would be incentivised to allow such ads. This is because such content can keep engagement numbers high and people on the platform, which increases revenue.

But the specific appetite they have for our health data is something we need to be particularly wary of. Big tech companies have had their eyes on our bodies and our healthcare in the past couple of years. In the US, Amazon is now selling medicine and is trying to compete with local health insurance to offer cheaper medications. In the UK, Amazon has signed a partnership with the National Health Service, as part of which they encourage people to use their Alexa devices for health queries.

Google on the other hand has acquired the company FitBit, whose smartwatches collect all sorts of data about our bodies: our heart rate, level of activities, sleeping pattern, etc…

Note as well that Noom tries to target employers in the US, with the promise that Noom will allow them to reduce their healthcare costs for their employees, by pushing employees to change their health habits through their “proprietary behavior change programs”.

As the race to derive more and more profits from our bodies and our health continues, it is essential for companies to treat our sensitive health data with the caution it deserves: it needs to be handled with special care and unique safeguards, and collected only when strictly necessary or with explicit consent. This is how we can ensure it will only be collected to protect us and improve our health and wellbeing, not for the profit of companies betting on people feeling insecure about their bodies.

Recommendations

For Google (as an AdTech company)

User control

- Provide logged-in users the option to opt out from all diet-related ads, not just ads from a single company.

Advertising policy

- Forbid dieting ads from being displayed to users who are known to be under 18.

- Limit available targeting criteria to prevent harmful targeting of people based on current or past diseases, illnesses, addictions or traumas.

Transparency and information

- Provide better transparency over the criteria used to target users with these ads (see our previous letters and our campaign for advertising transparency). People, regardless of the legal framework in their country of residence, should be allowed to properly understand why they are being targeted with these ads.

Security and privacy

- Analyse the URLs received through analysis and marketing tools to detect potential data leaks and report them to publishers (such as parameters like ?weight=xxx&height=xxx). Sanitise and remove these non-essential parameters before storing tracked URLs to avoid storing personal information according to the data minimisation principle.

Business practices

- Consider stricter due diligence on clients to avoid promoting problematic services, e.g. diet programmes that would be considered a scam by the FTC, programmes that would put the health of users at risk, etc.

For advertisers (companies selling diet programmes)

Data minimisation

- Do not collect unnecessary data, only strictly required data should be collected.

- Do not store data if unnecessary, prefer on the fly processing to make suggestions to the user when possible.

User information

- Inform users of their rights through accessible and user-friendly data privacy policies.

- Any data that is not strictly required should be labelled as such. The purpose for which the data, including non-essential data, is going to be used should also be clear to the user.

Legal Basis

- If you decide to collect and process sensitive data, make sure you have an appropriate legal basis (such as explicit consent under GDPR).

Security

- Perform security audits of your systems to avoid undesired data leaks such as with data stored in URLs and inadvertently shared with third parties.

For users

- Install an ad blocker and tell your friends and family to do the same.

- Favour trusted sources such as government health services and reputable non-profit health organisations websites.

- Check our guides to protect yourself from online tracking: pvcy.org/stoptracking.