Macedonia: Society On Tap

“This is my personal opinion,” concedes Branko, a taxi driver in Skopje, the Republic of Macedonia's capital. “It was done by America to stop Putin building his gas pipe line through Macedonia.”

“This is just politics,” he advises, skeptically.

It's a common reaction to the wiretapping scandal in Macedonia. Beginning in February last year when opposition leader Zoran Zaev posted a series of wiretaps online that he called 'bombs' – they seemingly showed that for years the phone calls of some 20,000 activists, lawyers, opposition members, journalists, civil servants, business people, and even members of the government had been unlawfully monitored. In June 2015, an assessment by senior rule of law experts appointed by the European Commission substantiated many of the claims.

Branko the taxi driver's opinion is understandable yet arguably manipulated. For several years the media landscape in Macedonia has been subject to a campaign of consolidation, media freedoms have been restricted and editorial policy controlled through ownership, financing, and personal relationships with senior staff. Macedonia was ranked 117th in Reporters Without Borders' 2015 Press Freedom Index, just behind Tajikistan and Qatar. In 2007, it was ranked 36th.

The opposition leader claims that the wiretapping was conducted by the Prime Minister at the time, Nikola Gruevski, and his cousin, Saso Mijalkov, who was at the time head of Macedonia's intelligence agency, the Administration for Security and Counter Espionage (UBK). Gruevski claims the wiretapping was conducted by foreign intelligence agencies in order to destabilise the country.

In such a controlled media space, it is difficult to know who to trust. Rumours thrive.

The immediate effects of the scandal have been far-reaching: mass protests led to the EU brokering an agreement leading to the resignation of both the Prime Minister and his cousin, and to new elections scheduled for June 2016. The long term effects of such wide scale wiretapping however will be felt by individuals and Macedonian society for years to come.

Opposition leader Zoran Zaev announcing the wiretaps and holding copies of the recordings. February 2015. Youtube

The "Sorosoids"

The climate of close control is familiar for those that experienced living in the former Yugoslavia. Macedonia was a constituent Republic of the socialist federation in which the communist party exerted tight control over the media and regularly spied on its people until its bloody break-up in the early 1990s.

In 1976, theatre director Vladimir Milchin was selected for surveillance by the party as an 'anarcho-liberal,' an opponent of the State. In 2000, he was able to read his file – for five years, the ruling party had been recording his conversations. There were transcripts of his conversations with family, with friends, with everyone.

This year, he received another transcript. This time however, it was in the form of CD, and the surveillance was not being conducted by a communist state, but by the intelligence agency of a modern European democratic republic.

In February 2015 the opposition party, Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) began providing victims with transcripts and CDs of their own intercepted phone calls.

“I wasn't shocked,” explains Vladimir, who went on to become the Executive Director of the Open Society Institute in Macedonia for 20 years, an international foundation supporting liberal civil society and individuals financed by multi-billionaire George Soros.

“What was disappointing was that it is now the same as in a one party communist state, where I'm judged to be an internal enemy.”

“On 21st April this year [2015], I was attacked in the street by a man wearing a hood... I've received death threats. One time I was told that my dead body wouldn't be buried in Macedonia. This is how opponents are treated in this country.”

Violeta Gligoroska, a life long activist and journalist who also worked at the Open Society Institute, received a similar batch of her own private conversations in May.

“It felt like I had been raped, like I had been raped by the State."

“My father was a communist dissident expelled from the party. For sure he was under surveillance. I never asked for the files. As my father was already dead, I didn't have the courage, the emotions, to go and to ask for it. I wanted the Ministry of Interior as far away from me as possible.”

“Unfortunately, that didn't happen.”

One of their colleagues who still remains at the Foundation, Slavica Indjevska, explains that it is regularly demonised by the pro-government press, characterized as foreign agents. They are derogatorily referred to as Sorosoids.

But surveillance of the foundation's employees does not just concern them. Even the most targeted surveillance also affects everyone who is in contact with the target; it is one of the main objectives and problems of modern surveillance. The job of the foundation's staff is to monitor social and political developments and to speak to journalists and Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs) about their projects, plans, and opinions. Because the Foundation was being surveilled, it gave the Government direct access to everyone they spoke to.

Slavica has yet to bring herself to listen to the CD in her office containing her recordings. On a Sunday evening she was preparing aid packages for refugees that are transiting through Macedonia when she received the phone call telling her that a file of her intercepted communications was available to collect.

“'You must be wrong,' I said... I was speaking to OSF colleagues all over the world where we have projects... It's such a bitter feeling, really an awful feeling when someone is in your private space without your consent. It's like having someone in your house, in your ear. It's just so personal.”

“This is the worst period in the country's history,” remarks Violeta, the experienced activist. “Even in the communist times, at least we knew we were being spied on.”

“We have taken Stasiland and translated it,” insists Vladimir, the theatre director. “It's just like East Germany; control by poisoning people with fear and propaganda.”

Slavica recalls voting in the independence referendum which saw Macedonia leave Yugoslavia in the early nineties. “I took my son and remember feeling like it could be a bright future for him. But something has gone wrong... during the nineties we witnessed hope and change, and people were motivated to look past their own individual position. But now we're going backwards.”

She's not optimistic about the future. “Simply when I see how much control, effort and money the state has, and the fear in people, with assumptions on their power by the economically weak, you're prone to manipulation, especially when you have no way out.”

Vladimir Milchin, 2015. Privacy International

The Journalist

Meri Jordanovska also received a phone call telling her to collect a CD containing her recorded conversations. She's currently a journalist at the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), a network of non-governmental organisations across the former Yugoslav republics promoting freedom of speech, human rights and democratic values.

She studied journalism at university. “When I was a first grader, I wrote my first article because I wanted to travel a lot, to write about different cultures. I thought that I would write about good stuff. When I was seven I knew that I would be a journalist because I wrote a lot, but in Macedonia it's hard to be a journalist at the moment at this time. So if you're with the government, you write pro-government text. If you do anything else, for example cover the refugees, you are seen as a traitor of the country, as a Sorosoid... Society is very divided, you are either with them or against. There is no in-between.”

“But the opportunity to make a change is what makes me want to be a journalist, still. There is still something inside that makes you want to dig deeper and deeper to find the truth.”

BIRN Macedonia recently published a report showing that the cost of a controversial 2010 government project to build a series of neoclassical monuments and buildings in central Skopje has jumped from the initial € 80 million estimated to € 560 million. In order to promote transparency around the projects, BIRN developed a publicly-accessible database documenting individual costs.

Some believe the new projects show how the government is looking to move Macedonia forward. Others, however, regard it as a nationalistic vanity project that is inexcusable in a country with one of the worst unemployment rates in Europe.

Government building, Skopje, 2015. Privacy International

Meri previously worked at Fokus, a critical independent investigative magazine founded by widely respected free speech pioneer Nikola Mladenov, who died in a car crash in 2013. The opposition leader Zaev is calling for the inquest into his death to be reopened, based on the wiretaps. “Today, audio conversations open the question whether the case can be closed as a tragic accident or there are indications that someone may have initiated the accident”.

Journalists at Fokus have been the subjects of civil defamation lawsuits by government officials, while its Editor-in-Chief Jadranka Kostova was recently named in a Lustration process as a former informant passing details on to the Yugoslav secret police during the 1990s, something she shares in common with Vladimir. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Special Representative for Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatovic, subsequently stated that the “decision could be seen as pressuring the magazine, endangering the media outlet and, consequently, having a chilling effect on media freedom”.

Prior to Fokus, Meri was at A1, then Macedonia's main independent pro-opposition TV station, which was forced to shut down in 2011 after an unpaid tax dispute with its owner. Reporters Without Borders later concluded that “The government clearly seized the chance to silence some of the few media that criticize it”.

Meri believes she was targeted for surveillance because of her association with A1 and Fokus. “This government doesn't want to be criticized. Instead of denying the stories, they attack the journalist personally.”

According to Meri, her recordings contained 5-6 conversations that she had had with opposition party members about the elections and the secret police. But no one has any idea how many of their conversations were actually recorded in total.

Particularly worrying for her was that she had been having deeply personal conversations with friends, as well as with Nikola Mladenov, her former and late colleague. “One of my colleagues received a recording of Mladenov congratulating them on the day their son was born.”

“Even that was being spied on.”

It also affects her professionally. She worries that potential sources will be reluctant to speak with her if they believe that their conversations may be being reported, while the fact that the opposition party has access to all the recordings also means that they now presumably have leverage over her and everyone that was being recorded.

The most shocking thing from the wiretaps for Meri was the extent of government influence in Macedonia, with evidence of senior government figures directly interfering in judicial appointments, editorial decisions across media, State appointments, and even interfering in the 2011 election through vote rigging and voter intimidation. The independent EU study concluded that the recordings appear to show “discussion of manipulation of the voter list; voter buying; voter intimidation, including threats against civil servants, and prevention of voters from casting their votes”.

“Every segment of society is under control. I have no faith anymore in the institutions. Everyone has connections to the party.”

Meri Jordanovska, 2015. Privacy International

The Academic

Jasna Koteska sees parallels and differences between surveillance practices back in Yugoslavia and modern techniques.

She is a Professor of Literature, Theoretical Psychoanalysis and Gender Studies. Her father Jovan Koteski was a famous Macedonian poet in Yugoslavia and subject to intense State surveillance for 42 years. “The present right-wing Macedonian government is, ironically, the closest approximation to the communist nomenclature in the post-communist era ... both being highly centralised organisations in which small cadres decide who is adequate and who is not, meaning that anyone disagreeing with the party is treated by the pro-Government media as anti-Macedonian, traitors, and Western protagonists.”

“It is a procedure essentially equal to what happened in the communist era, where people were routinely labeled interior enemies and dissidents. Ideologically, while the current party may be opposed to communism in favour of a nationalistic strategy, it is merely a change of perspective.”

Jasna is author of Communist Intimacy, a look at the nature of surveillance in Central and Eastern Europe during the socialist era. “Generally, as we all know, in most cases, it is [now] unimportant to have a huge number of actual informers on the field, since technology is already much better developed,” notes Jasna. “In all 46 years (1945-1991) of communist Macedonia the total official number of personal communist files is 14,572 (unofficial sources claim more than 50,000 files). The number of direct snitches in communist Macedonia was estimated at 12,000 to 40,000.”

Now, in a country of 2 million people, 20,000, or one in a hundred, were allegedly having their conversations recorded.

Jasna shared her in-depth analysis on the subject for Privacy International's blog.

Graffiti in Central Skopje, 2015. Privacy International

How Did This Happen?

Macedonia is an eager candidate for membership of the European Union. As with other candidate countries, EU candidacy weighs heavily on the internal politics and management of the State. The surveillance scandal and related protests led to an investigation by a group of senior rule of law experts appointed by the European Commission and an EU-brokered settlement among the two main parties, known as the Przino agreement. The agreement led to a Special Prosecutor being appointed to establish the factual evidence behind the surveillance, and to Prime Minister Gruevski agreeing to step down and call elections this year, in which he is eligible to run. Originally planned for April, the elections are now scheduled to take place on 5 June 2016.

Katica Janeva, endorsed by all the parliamentary political parties and appointed in September as the Special Prosecutor, is charged with investigating the wiretapping. Already however, pro-government media have been critical of the appointment, while the ruling party has said that it “no longer believes in her independence” and has “serious reservations” on the “legality of her actions.”

One of the main tasks of the Special Prosecutor is to ascertain how such widespread unlawful wiretapping could occur and for so long.

Privacy of communications is expressly guaranteed in Article 17 of the 1991 Macedonian Constitution, which states that “the freedom and confidentiality of correspondence and other forms of communication is guaranteed. Only a court decision may authorize non-application of the principle of the inviolability of the confidentiality of correspondence and other forms of communication, in cases where it is indispensable to a criminal investigation or required in the interests of the defence of the Republic.”

In 2005, a Law on Electronic Communications was first introduced to govern the relationship between the telecom operators and Government agencies entitled to access intercepted communications, undergoing several changes until a new law was introduced in 2014. Article 175 obliges operators to install the technology necessary for real-time interception of communications.

In 2010, the Ministry of Transport and Communications proposed an amendment to the law forcing telecommunications operators to provide direct and uninhibited access to traffic and other kinds of data to the Ministry of the Interior without prior notice or a court order. After its adoption, the constitutional court in Macedonia repealed the amendment following a petition by NGOs. However, Filip Stojanovski, a Program Director at the NGO Metamorphosis, which had challenged the amendment at the time, believes that the scandal shows that the court's decision was simply not followed.

The European Commission experts' report cites the Law on Electronic Communications as directly responsible for enabling the UBK to have direct access to the telecommunications networks:

Acting on the basis of Articles 175 and 176 of the Law on Electronic Communication, each of the three national telecommunications providers equips the UBK with the necessary technical apparatus, enabling it to mirror directly their entire operational centres. As a consequence, from a practical point of view, the UBK can intercept communications directly, autonomously and unimpeded, regardless of whether a court order has or has not been issued in accordance with the Law on Interception of Communications.

From the point of view of technical capability, the UBK holds the monopoly over the use of surveillance in both intelligence and criminal investigations. Surveillance is executed and monitored exclusively by the UBK on its own behalf, and also on behalf of the Police, Customs Administration and Financial Police. Therefore the UBK has the means to interfere in criminal investigations and, indirectly, to undermine the independence of the leader of the investigation (ie. the prosecutor).

Direct Access

Providing government agencies with uninhibited, direct access to telecommunications networks is a major but murky issue within the telecommunications sector, and one which they must confront.

In Macedonia, the telecommunications sector is dominated by companies operating under the global T-Mobile brand.

The formerly State owned Makedonski Telekom leads the provision of Fixed-line services. Their shares are 51% owned by Hungarian operator Magyar Telecom, which itself is a subsidiary of Deutsche Telekom, one of the world's leading telecommunications companies and the entity behind the T-Mobile brand.

After a process taking several years, on 1 July 2015 Makedonski Telekom merged into one legal entity with its subsidiary T-Mobile Macedonia, which had been the leading mobile operator in Macedonia.

Skopje city centre, 2015. Privacy International

Deutsche and Magyar Telekom declined to answer Privacy International's specific questions relating to the scandal, saying that Magyar had launched its own internal investigation.

Little is publicly known about how prevalent the provision of direct access by operators to State agencies is.

While there are technical standards across Europe for “Lawful Interception” codified by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), handover standards from the network to the agencies are premised on cooperation between telecommunications operators, Law Enforcement Agencies, and the provision of warrants or orders by authorised bodies.

Other standards, such as the Russian “SORM”, work to different specifications. In Russia and many formerly socialist countries that base their telecommunications and interception architecture on SORM, the system is more intrusive in that telecommunications companies have little meaningful opportunity to monitor and control state agencies' interception activities and/or mediate the access the state agencies have to the data of individuals using their networks.

Last year, one of the world's largest operators, Vodafone, revealed that some governments also had direct access to its networks, with no oversight by Vodafone.

In most countries, Vodafone maintains full operational control over the technical infrastructure used to enable lawful interception upon receipt of an agency or authority demand. However, in a small number of countries the law dictates that specific agencies and authorities will have direct access to an operator’s network, bypassing any form of operational control over lawful interception on the part of the operator. In those countries, Vodafone will not receive any form of demand for lawful interception access as the relevant agencies and authorities already have permanent access to customer communications via their own direct link.

Typically, the operators run their network on infrastructure consisting of switches, routers, and other nodes provided by large equipment vendors such as Ericsson, Cisco, Huawei, or Nokia. This equipment is generally designed to be compliant with lawful interception standards. For example, switches integral for ensuring that telecommunications networks function are themselves commonly used to forward intercepted data or content to a monitoring facility.

Some companies provide services and systems that are specially designed for lawful interception, such as monitoring centres in which law enforcement agencies receive intercepted material, and retention and mediation suites specially designed for lawful interception.

Other companies design and sell probes which passively collect and forward intercepts to agencies without the need to use network nodes, while other companies provide systems for passive collection of data on an indiscriminate, mass scale.

For more information on how different interception architecture functions, Privacy International has an analysis available here.

Although it has been established by the EU investigation that the UBK in Macedonia had themselves direct access, it has not been established how this was carried out technically and which companies provided the necessary equipment.

Who Provided The Surveillance Technology?

It is the job of the Special Prosecutor to ascertain how the interceptions were conducted technically, using which technology, and who it was provided by.

One of the first investigations undertaken is into claims that the surveillance equipment required to carry out the wiretappings was provide by an Israeli company.

In April last year, the opposition released an intercept which they allege shows that the head of the UBK demanded a payment of € 500,000 from a representative of the Israeli Ministry of Defence to proceed with the purchase, totalling some €14 million.

The Macedonian Interior ministry publicly claimed that the money was simply “a donation from our partner services in the Israeli government.”

The recording with what is alleged to be the Israeli middleman, some of which is in English, is still available online.

Recording alleged to show discussion between representitives of Gruevski and Israeli Ministry of Defence. YouTube

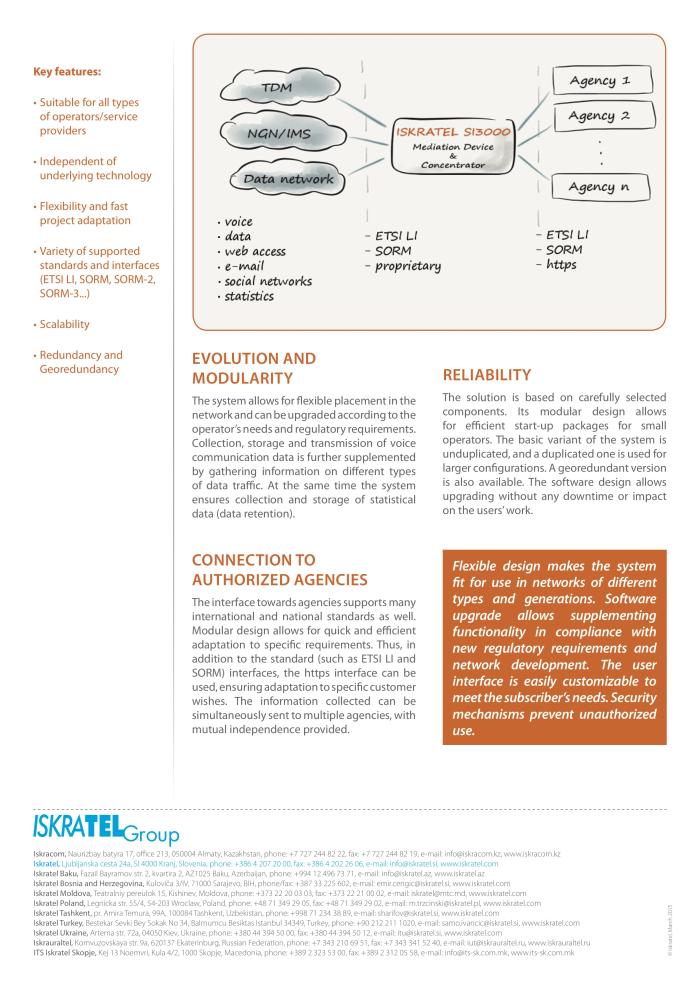

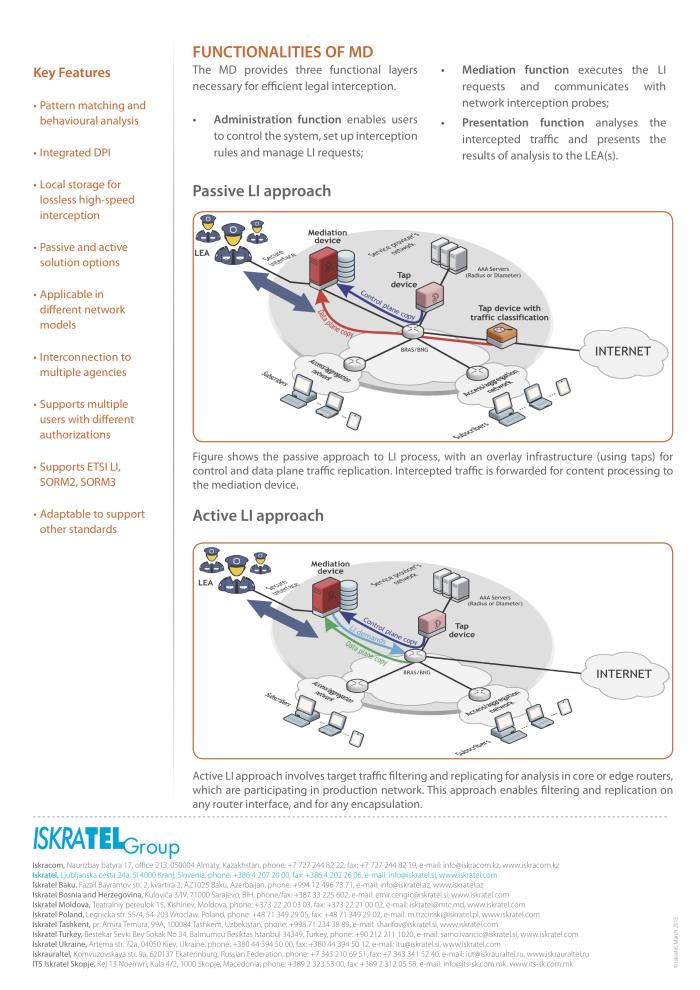

A little-known Slovenian manufacturer of telecommunications and surveillance equipment has been engaged in a variety of lawful interception projects in Macedonia.

Iskratel in Macedonia has implemented projects allowing for the lawful interception of the fixed-line network of Makedonski Telekom, and has carried out projects ensuring the lawful interception of various of their network nodes, including a node which allowed for IP Lawful Interception and the development of software used to visualise intercepted data on SORM3 protocols, according to records seen by Privacy International.

Based in Kranj, Slovenia, Iskratel develops and sells IP and fixed-line Lawful Interception (LI) systems to customers across the world. It has been represented at the world's most notorious closed conference on electronic communications surveillance, ISS World, in 2014 and 2015 where it presented on its Lawful Intercept solutions. In June this year, it invited delegates at ISS World to visit their stand saying that it was “strengthening solutions portfolio in the field of Legal Interception for Telecom Operators and Agencies. This year at ISS we will present scalability extensions to Iskratel’s lawful interception solution and a new SI3000 based IP LI in Data Retention All-in-one solution.”

Their brochures, below, advertise both their retention suites for fixed-line Lawful Interception, and their internet interception system.

For lawful interception, Iskratel built a universal, highly flexible traffic-monitoring solution. The solution supports ETSI LI, SORM2 and SORM3 recommendations, and can be used in various IP-based networks – either fixed or mobile, either wired or wireless. The solution is based on the big-data concept – a concept that includes tools, processes and methods that a LEA needs to handle the new traffic types, large amounts of data and storage facilities.

SORM2 is the Russian-based interception standard which applies to all IP traffic, while SORM3 “takes care of collecting all communications, their long-term storage and access to all subscribers’ data,” according to Andrei Soldatov, a leading authority on the SORM standards.

Iskratel describes itself on its Macedonian website as “the major provider of Telecommunication equipment in Republic of Macedonia in the last 60 years and leading system integrator for design, implementation and maintenance of ICT solutions.”

When asked to respond to our analysis, Iskratel replied to say that their “systems must, correspondingly with laws of each country, also ensure the so-called "lawful interception" functions. While confirming this, we can assure you, that Iskratel was never conducting or was a part of any interceptions, legal or not. Iskratel is firmly against any and all means of unauthorized interception.”

Seminar on the mandate of the Special Prosecutor, Skopje, 2015. Privacy International

How To Fix This

“There is no legal mechanism that can fix this,” says an audience member to Zarko Trajanovski, a human rights law expert, activist, and blogger, at a public seminar on the scandal in the Holiday Inn in Skopje. “We have surpassed the doings of Fidel Castro.”

There is of course no single solution to ensure that the type of wiretapping seen in Macedonia doesn't reoccur in Macedonia or elsewhere. Zarko, however, points out that any solution must be holistic in nature, requiring reform of all of the Macedonian authorities and institutions, and organised action by all groups in society. As the EU Commissions' Group of Senior Experts' review makes clear, the problem is not that the legal framework governing surveillance in Macedonia is inadequate, but that there is a “considerable gap between legislation and practice,” and specifically a “lack of proper, objective and unbiased implementation.”

Zarko also agrees that foreign companies such as Deutsche Telekom played a role in the scandal and have a role to play in the solution.

Network operators providing direct access to state agencies should not be allowed under any circumstances. The large multinational network operators, far from being innocent providers of services which governments take advantage of, must take strong, concerted action in order to ensure that they are not complicit in wide-scale abuses. Transparency reports are a good start, but proactive action such as legal challenges and industry-wide initiatives must be prioritized.

In addition, it is essential that the trade in lawful interception-related and other surveillance technology, which often sits on top of the network infrastructure itself, be better regulated. If the legal framework in a country is inadequate, or the record of a customer shows that they are complicit in human rights abuses, surveillance systems should not be provided to them given the risk of their abuse or use in violation of international human rights law.

As the ongoing wiretapping affair in Macedonia shows, the implications of surveillance on such a mass scale can be devastating. The ruling party has been able to exert an enormous amount of political control over every sector and institution in Macedonia, including the media, civil society, judiciary, and civil services, empowered by the intelligence it has gained from using modern telecommunications surveillance techniques. As the EU experts' report concludes:

The scale of the unlawful recording of conversations, the concentration of power within the [Administration for Security and Counterintelligence] UBK, the over-wide remit of the UBK's mandate (which, despite its considerable breadth, was nevertheless exceeded) and the dysfunctional external oversight mechanism have resulted in a number of serious violations:

- Violation of the fundamental rights of the individuals concerned;

- Serious infringements of the personal data protection legislation;

- Violation of the 1961 Convention on Diplomatic Relations (Vienna Convention), given that diplomats have also been illegally intercepted;

- Apparent direct involvement of senior government and party officials in illegal activities including electoral fraud, corruption, abuse of power and authority, conflict of interest, blackmail, extortion (pressure on public employees to vote for a certain party with the threat to be fired), criminal damage, severe procurement procedure infringements aimed at gaining an illicit profit, nepotism and cronyism;

- Indications of unacceptable political interference in the nomination/appointment of judges as well as interference with other supposedly independent institutions for either personal or political party advantages.

As the EU was heavily investing in democratization and liberalisation projects, the fact that the ruling party had access to the personal communications of some 20,000 people, including during a general election, effectively means that many of these efforts have been wholly undermined.

Ensuring that this does not happen again in Macedonia or elsewhere requires a holistic, comprehensive approach, reliant on ensuring that appropriate legal frameworks in line with international human rights standards exist, that States have good levels of governance with transparent institutions and an accountable security sector, that industry takes a pro-active role, and that individuals have access to secure networks and devices and know how to secure themselves. Safeguards to stop the export of surveillance systems and make the industry more transparent can and must also form part of this solution. Externally, it is up to the EU and its Member States to take the first steps to ensure that European companies do not only undermine individuals' human rights, but also that the very policies that they themselves are pursuing in Macedonia through the enlargement process are not also undermined.

Privacy International will be working with industry and regulators to try to ensure thatprohibit systems where intelligence agencies are provided with direct access to telecommunictions networks, such as in Macedonia, do not exist, and that to develop international standards for surveillance that protect individuals' right to privacy from such abusive practices.

It is in Macedonia however, where redress and progress needs to be achieved. This is now the job of the Special Prosecutor, journalists, civil society, politicians, and its citizens.

Disclosure: Privacy International is also partly funded by the Open Society Foundation