Obfuscation And Work Arounds: How The Intelligence Agencies Have Been Obtaining Communications Data

Privacy International’s case on Bulk Personal Datasets and Bulk Communications Data comes to a head with a four-day hearing in the Investigatory Powers Tribunal which commenced on 26 July 2016.

The litigation has brought to light significant revelations about the use of section 94 of the 1984 Telecommunications Act to obtain bulk communications data.

Large amounts of disclosure have shed new light on this hitherto secret power and explained confusing aspects of the Government’s Response to the litigation. Although as we set out below, this often leads to more questions than answers.

Here we look at one puzzling aspect in the Government’s Response to the litigation, the omission of ‘subscriber information’ – the name and other identifying information of the person using a particular communications service -- from the types of communications data collected under the section 94 regime. Typically, communications data is split into ‘traffic data’, ‘service use information’ and ‘subscriber information’.

As a result of disclosure and following the publication of Sir Stanley Burnton’s review of section 94 we have a partial explanation for the omission of ‘subscriber information’ from the section 94 regime. The short answer, is that until very recently subscriber information was being collected using section 94. And even if it isn’t collected now, that does not reduce the intrusiveness and potentially very revealing nature of the remaining communications data that is being obtained and retained on a mass scale.

Background

In November 2015 the Home Secretary, Theresa May, acknowledged for the first time that the Intelligence Agencies had been collecting bulk communications data [‘BCD’] using section 94 of the Telecommunications Act 1984, aka ‘section 94 Directions’.

Subsequently, in the course of PI’s litigation, it was admitted that GCHQ have used section 94 to collect BCD since 1998 and the Security Service has acquired BCD from communications service providers [‘CSP’s] since 2005.

A CSP [referred to as a CNP by the Intelligence Agencies] can be a company such as BT, Vodafone or Virgin Media, that provides access to internet and telephony services through its network infrastructure. [Intelligence & Security Report 2013]

As stated by the Intelligence Agencies:

“Bulk Communications Data…involves large amounts of data, most of which relates to individuals who are unlikely to be of any intelligence interest.”

What is communications data

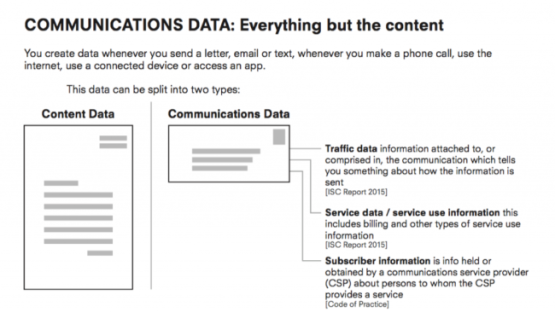

You create data whenever you send a letter, email or text, whenever you make a phone call, use the internet, use a connected device or access an app. This data is split into two categories:

Communications data: the who, when, where and how of any communication including our internet activity and telephone calls. It includes, but is not limited to, visited websites, email contacts, to whom, where and when an email is sent, map searches, GPS location and information about every device connected to every Wi-Fi network.

Content data: the substance of the message (e.g. “Dear John, Thank you for your email . . . “).

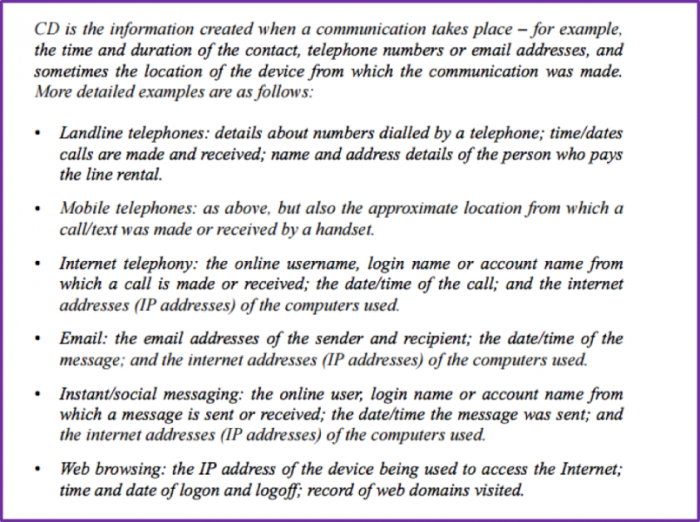

The Intelligence and Security Committee in their 2015 report set out examples of communications data:

The intrusive nature of communications data has been highlighted in the recent opinion of the Advocate General of the European Court of Justice, Henrik Saugmandsgaard Øe:

“I would emphasise that the risks associated with access to communications data (or ‘metadata) may be as great or even greater than those arising from access to the content of communications…metadata facilitate the almost instantaneous cataloguing of entire populations, something which the content of communications does not.”

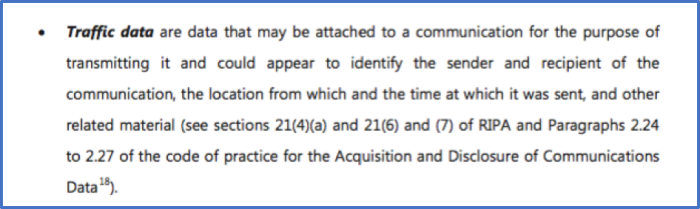

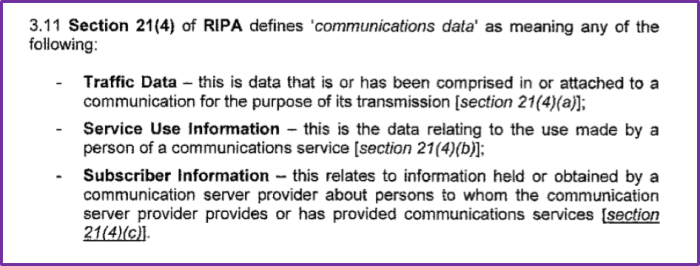

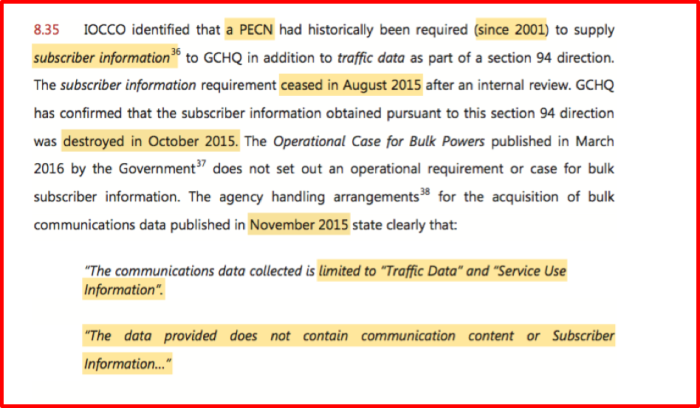

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 further splits communications data into three types: traffic data; service use information; and subscriber data.

- “Traffic data” can be understood as including caller line identity, dialed number identity, cell location data and other details of the location or ‘address’ of a sender of recipient of a communication e.g. X phone number called Y phone number at 1:30 a.m. on 1.7.2016 for 5 minutes, while X was located at 123 High Street, London. With enough signal strength you could see whether the phone was at the front or back of the house, using multiple towers to triangulate location.

Stanley Burnton, the Interception of Communications Commissioner confirms in his 2016 Review of section 94, that location data is collected as part of traffic data.

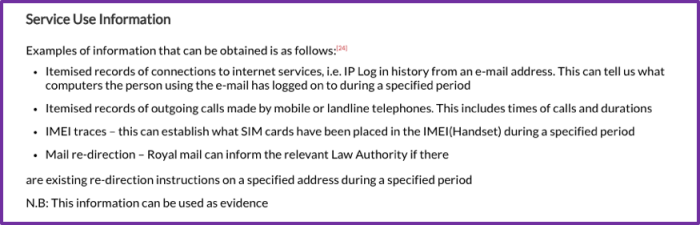

- “Service data” / “Service Use Information” is data relating to the use made by any person of a communication service and may be the kind of information that habitually used to appear on an itemized billing document supplied to customers (s.21(4)(b) of RIPA and paragraphs 2.28 and 2.29 of the code of practice for the Acquisition and Disclosure of Communications Data.) It includes billing and other types of service use information such as call waiting and barring, redirection services and records of postal items;

E.g. your mobile phone was switched on at 8:00 a.m. on 1.1.2016 and logged into various different mobile phone towers between 9:00 a.m. and 9:30 a.m. It has been connected to the same tower for the last three hours. The pattern roughly repeats itself every Monday through Friday.

- “subscriber information” is data held or obtained by the provider of a communications service ‘in connection with’ the provision of the service. This may be the kind of information which a customer typically provides when they sign up to use a service e.g., the recorded name and address of the subscriber of a telephone number or the account holder of an email address, bank details and details of credit cards etc attached to a user’s account (see section 22(4)(c) of RIPA and paragraphs 2.30 and 2.38 of the code of practice for the Acquisition and Disclosure of Communications Data (footnote 18)).

Subscriber information is not sent with the communication thus on a technical perspective its inclusion in the communications data definition can seem confusing, as it is not data that forms part of the communication, but rather is a dataset that can be linked to a communication by, for instance, a telephone number or an IP address.

Communications Data – not bulk

Before we look at the use of section 94, it is worth reminding ourselves what we know from the 2013 Intelligence and Security Committee Report - the Security Serve were using RIPA to obtain subscriber data i.e. communications data that contains names and addresses.

It was not known at this time that they were also obtaining communications data in bulk using section 94. As stated earlier, whilst section 94 was used by the Security Service form 2005, it was only revealed in 2015.

19. When we questioned the Agencies during this Inquiry on how they accessed CD [Communications Data], and for what purposes, we were told that the Security Service is by far the greatest user of CD, making *** requests a year under Part I, Chapter 2 of RIPA…Around half of these applications are for subscriber data only (i.e. the registered owner of a telephone number or email address).

[ISC Report 2013 : Written Evidence – Home Office 19 September 2012]

What do the Intelligence Agencies say about their collection of subscriber information?

According to the Government’s Response to the litigation, bulk communications data provided by the CSP’s under section 94 is limited to ‘traffic data’ and ‘Service Use Information.’ The Government argues this thereby makes the data collected under section 94 anonymous. The Government states in it’s Response to the litigation:

13) The data provided does not contain communication content or Subscriber Information (information held or obtained by a CNP about persons to whom the CNP provides or has provided communications services). The data provided is therefore anonymous. It is also data which in any event maintained and retained by CNPs for their own commercial purposes (particularly billing and fraud prevention).

225)…

The information to which MI5 Closed Section 94 Handling Arrangements relate is defined in section 2. §2.1 notes that the communications data provided by the CNPs under the section 94 Directions is limited to “traffic data” and “Service Use Information” (as defined at §3.11, citing section 21(4)(a) and (b) of RIPA) [REDACTED].

The Government’s Closed Section 94 Handling Arrangements referred to above set out the RIPA definitions of communications data:

Why is subscriber information important?

Whilst the Government state that:

13) The data provided does not contain communication content or Subscriber Information … The data provided is therefore anonymous.

Sir Stanley states that:

Traffic data…could appear to identify the sender and recipient of the communication…

It is Privacy International’s position that holding traffic data and/or service use information without subscriber information does not result in the data being anonymous. This data contains an individuals’ unique patterns and behavior, such as the newspaper they read online, for how long and at what time; or an individual’s unique use of the infrastructure such as make, model and software version. It is only anonymous in the sense that it does not contain your full name and address. Using traffic data or service use information individuals can be singled out, tracked and profiled. Their pattern of activity is unique and their device is like a fingerprint, particularly when location is included.

Recent revelations

Whilst the recently released review of section 94 by Sir Stanley Burnton shows that subscriber information is not currently collected:

8.34 All of the extant requirements for bulk communications data are for traffic data as defined in section 21(4)(a) of RIPA. All of the current directions require regular feeds of bulk communications data to be disclosed…

that has not always been the case.

According to Sir Stanley, at least one PECN (Public Electronic Communications Networks) i.e. communications provider, provided subscriber information to GCHQ until August 2015. This data was destroyed in October 2015, one month before the publication of the ‘handling arrangements’, thus avoiding the need to disclose that subscriber information had been collected - as it was no longer current practice. It also avoided the need to make an operational case for ‘subscriber information’ within the Operational Case for Bulk Powers.

Following this, the Government stated that:

One specific BPD obtained under the terms of section 94 has been stored in the main BPD repository. The requirement for this data ceased in August 2015 and all such data had been destroyed by October 2015. The BPD tools are not made available to other government organisations. Integrees form other Departments who are based at GCHQ may have access but only for GCHQ purposes.

GCHQ’s Bulk Personal Datasets Closed Handling Arrangements further state:

4.2 GCHQ obtains bulk personal datasets in a variety of ways, for example…creation of a discrete bulk personal datasets from material intercepted under warrant (or acquired under a section 94 direction) …

Raw data acquired … from directions under s.94 of the Telecommunications Act 1984 may meet the strict definition of bulk personal data but such data is subject to specific handling arrangements and safeguards (including default retention periods) and is not considered to be bulk personal data in this context.

What this indicates is that GCHQ obtained subscriber information using section 94 and then stored it as a Bulk Personal Dataset.

Conclusion

With pieces of the puzzle still missing it is hard to draw firm conclusions, but at the very least we know:

- GCHQ and the Security Service were using section 94, a power kept secret from the public and Parliament from 1998 to 2015, to collect huge quantities of traffic and service use information via regular feeds from Communication Service Providers / PECNs.

- We now know that GCHQ were in fact also obtaining subscriber information until 2015 using section 94.

- GCHQ stopped obtaining subscriber information in bulk under section 94 in August 2015 and destroyed the data in October 2015 - before publication of the handling arrangements for bulk communications data and the publication of the operational case for bulk powers.

- GCHQ stored bulk subscriber information as a bulk personal dataset.

- The Security Service were using RIPA to obtain subscriber information, as stated in the 2013 ISC Report.

We are thus left questioning why did the Security Service, unlike GCHQ, avoid using section 94 to obtain subscriber information. Did they assess that obtaining subscriber information would engage Article 8 ECHR and thus undermine their (erroneous) assessment set out in correspondence from 2004 to the Interception Commissioner that transfer of bulk communications data did not engage Article 8? Is that why they used RIPA instead?

Alternatively, did they use RIPA to obtain subscriber information in order to give the impression they were only making non-intrusive requests for reverse directory lookups, when in fact the data obtained via RIPA was used to enrich bulk communications data obtained via section 94?

Would the Security Service use the subscriber information obtained via RIPA to match, for example, an IP or IMSI to a name and address? Did the activities of matching traffic data and service use information with subscriber information also involve Bulk Personal Datasets containing subscriber information?

Why did GCHQ obtain subscriber information via section 94 and appear to operate a different regime or analysis of the legal justification to the Security Service? Why did they suddenly stop using section 94 to obtain subscriber information in 2015 and destroy the data? Were they worried about public reaction or did they want to say that the data they held was anonymous?

It is disappointing that the Agencies have been unable or unwilling to be upfront about the scope and personally identifiable nature of the information they collect. Instead we must rely upon disclosures in reports for a drip feed of transparency.