Project Hunter: The UK Programme Exporting its Border Abroad

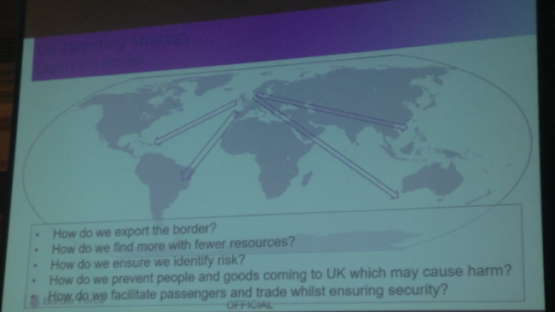

The UK border authority is using money ring-fenced for aid to train, finance, and provide equipment to foreign border control agencies in a bid to “export the border” to countries around the world.

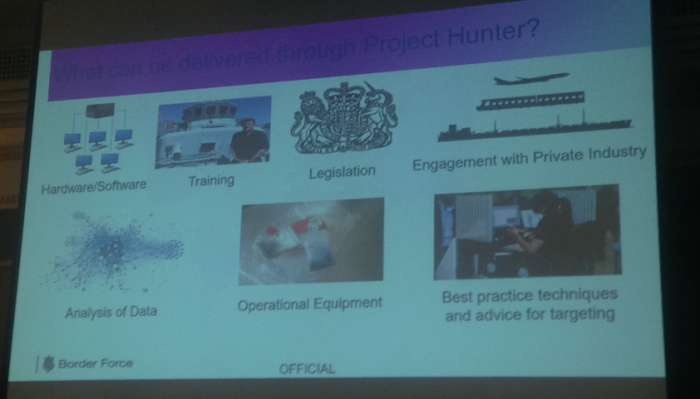

Under the UK Border Force’s “Project Hunter”, the agency works with foreign security authorities to bolster their “border intelligence and targeting” capabilities with UK know-how and equipment.

As well as the provision of equipment and training, the Border Force is also advising countries on amending legislation to facilitate data gathering and targeting, as well as providing data analysis services.

The project raises serious concerns regarding the diversion of aid money, the international transfer of discriminatory or otherwise unlawful surveillance capabilities, and the transfer of sophisticated privacy-invasive capabilities to countries with significant governance, rule of law, and human rights concerns.

According to a Border Force presentation given to border control authorities in Morocco, the body - which has responsibility for immigration and customs across the UK - has engaged with authorities in 28 countries over the past 3-4 years, including with border, drug enforcement, and intelligence agencies.

Under the programme last year, intelligence and targeting training was delivered to 85 officers from the UAE, as well as members of the Nigerian Drug Law Enforcement Agency. In the UK, the Border Force Targeting Academy trains foreign security authorities in capabilities including passenger targeting, intelligence and information, and behavioural detection.

The project is Official Development Assistance (ODA) funded, meaning that all the cost of the project goes towards the UK’s foreign aid spending target of 0.7% of GNI – a high-profile spending commitment made by successive British governments during controversial budget cuts across other government departments.

State Sponsors of Surveillance

Project Hunter is part of a broader trend of countries with sophisticated surveillance capabilities training, financing, and equipping foreign security agencies. As data-gathering is increasingly used by these countries to investigate people, conduct intelligence, and deter migration, they are also exporting them to other countries.

The Home Office for example, which is responsible for law enforcement in the UK including the Border Force, also promotes its highly criticised counter-terrorism ‘Prevent’ programme to highly sensitive regions abroad, including Xinjiang in China where residents are subject to some of the most pervasive surveillance in the world.

As outlined in Privacy International’s report last year, a dizzying array of government and intergovernmental agencies currently provide such assistance to countries around the world. Providers include development, law enforcement, and intelligence agencies from China, the US, and Europe, as well as institutions such as the European Union, International Organisation for Migration, and the World Bank.

While such initiatives have the potential to benefit people, they risk:

- Diverting money away from aid and development projects, including projects focusing on education, promoting rule of law, and good governance which actually prevent conditions conducive towards insecurity

- Facilitating human rights abuses and authoritarianism by promoting practices and laws that are not compliant with international standards

- Facilitating human rights abuses and authoritarianism by capacitating unvetted agencies or personnel

- Diverting money away from aid and towards a donor countries’ commercial interests; a process which is often heavily influenced by corporate interests

- Facilitating corruption

- Signalling a country’s or donor’s approval of an agency or country’s leadership

- Capacitating actors who are not the intended recipients, such as violent non-state groups.

Earlier this year, leading aid charities in the UK wrote a letter to the Government warning that over a third of the aid budget was being spent on upper middle-income countries to further the UK’s own commercial and national interests, to the detriment of the world’s most vulnerable people.

In the UK, any such training or assistance of foreign security agencies is supposed to be subject to an assessment aimed at minimising the potential to facilitate human rights abuses, known as the Overseas Security and Justice Assistance Guidance (OSJA).

But the assessments are not public, meaning it is impossible for the public to know how effective the safeguards are in practice. Last year, a review by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact expressed concerns “as to whether these assessments are an effective control mechanism” after finding cases in which assessments conducted by Government departments were either “incomplete or of low quality” or ignored altogether.

There is little public information available about Project Hunter, which further exacerbates these risks. Privacy International has asked the Border Force to provide more information regarding the project, associated safeguards, and whether it has completed any such OSJA assessments; it has so far failed to respond. We will update this page with any response.

Borders without Borders

The export of such border control measures is also being pursued by other wealthier nations aiming to deter immigration; the US government and numerous European Union institutions and member states are currently engaged in projects which aim to export border controls to foreign countries, similarly to Project Hunter.

The EU’s next billion-Euro budget, which will see funding on migration and border control nearly triple to €34.9 billion, will also see huge increases across multiple areas for working with non-EU member countries’ to boost their border control authorities. The process of finalising the budget is currently underway.

Democratic pressure is needed across Europe and the world to ensure that aid money is not diverted from the most vulnerable, and to ensure that safeguards and accountability measures exist. Without such measures, these initiatives risk using resources meant to protect the most vulnerable to endanger people around the world.