How Privacy and Data Protection Law Can Help Defend Migrants' Rights

Technology and data are increasingly used for immigration enforcement, putting migrants’ fate in the hands of systems driven by data processing and algorithmic decision making.

As the UK plans a future of dynamic risk assessments for visa applicants, the collection of biographic and biometric data and automated data sharing, we explore the degree to which privacy and data protection laws can defend migrants against abuses of their data and seek redress when their rights are denied.

In a roundtable available on YouTube, co-hosted with Garden Court Chambers, Privacy International brought together immigration law practitioners to discuss how they’ve used privacy and data protection law to seek information or redress for their clients.

Index:

1. UK Border 2025

2. Super-complaint and judicial review challenge to data sharing

3. Mobile phone seizure and extraction

4. Freedom of Information Act requests

The dystopian future: UK Border 2025

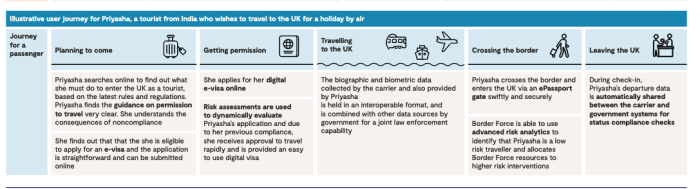

To set the scene on how the future may look when we consider challenges that can and have been brought to data intensive systems, first consider the UK Border Strategy 2025. This document, intended for trade and industry in relation to post-Brexit controls, includes the ‘expected’ journey of a person through the UK border in 2025. In doing so, it gives a sense of the significant data gathering exercises that are intended in the future.

Priyasha, a tourist form India wishes to travel to the UK for a holiday by air.

- risks assessments are used to dynamically evaluate her application;

- biographic and biometric data is collected by the carrier and held in interoperable format and combined with other data sources by government for a joint law enforcement capability. (interoperable i.e. across different platforms).

- advanced risk analytics to identify traveller ‘risk’ and allocate Border Force resources are conducted.

- automatic data sharing between carrier and government systems for compliance checks is carried out.

At first glance, initial questions arise when looking at this scenario: what are the risk assessments; what information are they based upon e.g. nationality or location; how would they be used; could migration and health data be linked; what are the consequences if data in the system is incorrect.

If we think about nationality and location, could such a system use information produced by models such as the Danish Refugee Council and IBM’s ‘Foresight Model’. This uses machine learning to predict total forced displacement from a given country 1-3 years ahead. The system aggregates data from 18 sources, and contains 148 indicators along several dimensions. If you are from a country which is predicted to see a rise in forced displacement, will that affect your score?

Or could your risk assessment be affected by changes in the price of goats? This measurement is one of ‘nesting behaviour’, being behaviour that gives an indication that something is about to happen. In the case of goats that, in certain countries, if the price falls, this would indicate an impending wave of migration.

The context of Home Office IT failures

In addition to the risks to human rights and the privacy implications of such data gathering and enrichment through combining with other sources of data, it should be noted that the UK Border plans emanate from a government department which has faced strong criticism by the Public Accounts Committee in March 2021 for the “staggering” cost of Home Office border security tech failures. The Committee stated the Home Office continue a miserable record of exorbitantly expensive digital programmes that fail to deliver for the taxpayer or for border security.

Challenge to data sharing between public authorities

Super-complaint

One way to challenge data sharing between public authorities is via a super-complaint.

In 2018 Liberty and Southall Black Sisters brought the first ever police super-complaint, under section 29A of the Police Reform Act. This is a scheme designed to allow designated bodies to raise issues on behalf of the public about harmful and systemic practices by the police.

This super-complaint challenged:

- The police passing victim and witness data to the Home Office for immigration enforcement purposes; and

- The operation of and/or perception of a culture of police prioritising immigration enforcement over the investigation of crime and safeguarding.

This was a case where individuals were too scared to come forward to challenge the data sharing between the police and Home Office, due to the risk of being deported.

It was argued that the data-sharing, which included all victims even those who are victims of extremely serious crimes such as rape, modern slavery and human trafficking, undermined the fight against crime. It had a real deterrent effect on people with insecure immigration status seeking the support of the police. As a result, victims were unable to access justice while perpetrators remained free to commit further crimes and threaten public safety.

Home Office policy

When Liberty and Southall Black Sisters started the case, there was no policy on sharing and it was done on a random adhoc basis. Liberty and SBS argued that there had to be a policy, in order to ensure consistency as public law principle in this context.

A policy was then produced by the police, which said:

(1) That ordinarily, police will share any suspicion that a victim or witness of crime is of uncertain or unsettled immigration status. They will share that with the Home Office.

(2) The policy also said that the primary purpose of police in this situation was to protect the victim.

(3) It also said the police would take no enforcement action. they woudl just hand on the details to the Home Office to leave it to them.

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS), the College of Policing (CoP) and the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) published their December 2020 report responding to the Super-Complaint. The report called for an overhaul of the laws and policies on police data-sharing with the Home Office.

Judicial review

Liberty also sought to challenge the first part of the policy, that “ordinarily the police will share any suspicion that a victim or witness of crime is of uncertain or unsettled immigration status.”

The Judicial Review grounds included:

Ground 1: Articles 2 and 3 European Convention.

- Articles 2 & 3 include positive obligations to put in place an administrative framework, being systems and policy, which provide practical and effective protection against serious crime. [see e.g. Balsan v Romania 2017 - a victim of domestic violence must have system in place by which they can complain about being victim and seek the authorities protection.]

- The evidence that victims will be deterred reporting crime, because they are concerned they will handed over to the Home Office, meant the administraitive famework did not provide pratical effective protection against crime, as people would not report crime.

Ground 2: related to Article 8. Looked first at whether there was an interference (sharing of data did interfere) and secondly whether it was justified.

- This ground relied on The Christian Institute v The Lord Advocate (data about children shared between public authorities for the purpose of safeguarding. Interferred with Article 8 and incompatible as neither children nor parents asked for consent.)

- Was there an interference: yes

- Was the interference justified:

- It caused serious harm. It prevented victims of serious crime such as rape, threats to kill, from having protection from the police.

- sharing of data was inconsistent with primary purpose of policy. Primary purpose was that police should be protecting victim. Sharing data was inconsistent with that as victims would not come forward and so have no protection.

- data sharing was justified by Home Office for purpose of immigration enforcement but, it did little or nothing to achieve that. First the police were not going to pursue immigration enforcement. No evidence that data sharing with Home Office led Home Office to take any enforcement action against indivdiuals.

- There is caselaw that indicates a public authority may be required to put forward evidence to show that a justification they put foward is effective in a particular case. see e.g. Quila v The Home Department, Supreme Court (no evidence Home Office policy deterred forced marriage)

Ground 3 related to Article 14, discrimination.

- Sharing of data was direct discrimination on grounds of immigration status.i.e. data was shared if ‘unsettled’ but not if ‘settled’.

- Failure to make exceptions to the rule e.g. for victims of domestic violence.

- i.e. difference in treatment ongrounds of status.

- advantages of Article 14 is broader range of statuses protected. Much more limited under Equality Act. Includes immigration status under Article 14. However, direct discrimination is justifiable under Article 14 but not under Equality ACt.

- Also put forward Thlimmenos argument, CASE OF THLIMMENOS v. GREECE - this is the argument that if the state fails to make exception to a policy or rule for a group that is signficantly different, then that itself may be unlawful in discrimination. in this case victims of domestic violence should not have data shared. Example of this is the case of OA v Secretary of State for Education.

- Test of justification: was the discriminatino or failure to make an exception justified.

Permission was granted. The police withdrew the initial policy then issued a new one, which was withdrawn and re-issued. They also included additional justifications such as sharing was for safeguarding reasons. Against this the Claimants argued that sharing should be based on consent (s.35 DPA 2018 and Article 8, Christian Institute case). The claim initially proceeded however, when the Claimant was given a chance of status the claim was abandoned. Meaning the issues have not been resolved.

Data Extraction and mobile phones

Daniel Carey discussed litigation which has recently been heard in the High Court, in which PI intervened involving the widespread seizure of migrant’s phones on arrival in the UK via small boat. This had serious impact on migrants who lost contact with family and friends, lost evidence supporting asylum claims, hindered access to legal assistance in the UK and establishing support and social networks in the UK.

The claimants sought judicial review of the Home Office’s MPE policy and practice, on the following grounds:

- The search of the Claimans’ persons and seizure of the Claimants’ phones were unlawful (under the Immigration Act 1971 and Immigration Act 2016 respectively).

- The Home Office did not have a right to compel provision of the PIN numbers of asylum seekers - this demand represented a very serious abuse of power, especially given the imbalance of power in these circumstances.

- The Home Office’s MPE policy was unlawful because it was secret, blanket and fettered (i.e. leaving no discretion to individual officers as to when and how to apply it).

- The policy of phone seizure and retention constituted a disproportionate infringement of the Claimants’ rights under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR’).

- The seizure and retention of phones, and the extraction and further use of data, were incompatible with the Home Office’s obligations as a data controller under the Data Protection Act 2018 (‘DPA 2018’).]

- The extraction and further processing of data from the phones constituted a disproportionate infringement of the Claimants’ rights under Article 8 of the ECHR

Freedom of Information Act

Oliver Persey then set out the nuts and bolts of the Freedom of Information Act which can be used to request information. Other tools include subject access requests, parliamenary questions, writing to the Home Office, pre-action letters engaging duty of candour and cooperation.

In relation to the Freedom of Information requests this must be a valid request for information. There are grounds for refusal of the request which include cost limits and whether it is vexatious. There are ways to challenge refusals which include internal review, complaint to the ICO and appeal.

His list of tips and tricks included:

- Using the FOIA Code of Practice

- FOIA relates to information not documents

- Pre-empt exemptions

- Make the mostof the advice and assistnace duty (s16)

- Look for ‘wins’ in refusals

- Look for other oFOIA requests on whatdotheyknow

- Think ‘How else can i get this information’

Where next?

In terms of challenges to the treatment of migrants, Louise noted that the EU Parliament refused to fully fund Frontex, the EU’s border and coastguard agency, over concerns about allegations of rights violantions, hiring failures and harassment by senior Frontex staff. She highlighted human rights law, equality and non-discrimination law, procurement law and new rules relating to Artificial Intelligence as areas to consider when bringing challenges.

Adam noted other routes to challenge data sharing between public authorities include GDPR Article 5.1(b) and recital 50, indicate that data processed for one purpose should not be processed for another that is incompatible with the first purpose i.e. NHS sharing with Home Office for enforcing charging policy, if then Home Office use for immigration enforcement you could argue that is incompabile.