Who profits from the UK's 24/7 tracking of migrants?

The UK puts migrants under 24/7 GPS surveillance. As usual, private companies are outsourced to deliver this hostile policy - who are they? We've investigated.

Five companies lie at the heart of the UK’s GPS tagging system: Capita, G4S, Airbus, Telefonica and Buddi. It’s a complex entanglement of private third party responsibilities, with Capita as a core actor.

The rise of racist and xenophobic narratives around the world has led to a ramping up of brutal migration control policies. Indefinite detention, pushbacks of boats at sea, or deportation for offshore processing of asylum claims all now form part of the arsenal deployed by some governments to “appear tough” on and provide "solutions" to immigration. A stark example is the UK’s “hostile environment” policy, announced 10 years ago by then Home Secretary Theresa May and designed to deter migrants from entering the UK or encourage them to leave voluntarily. While there is no evidence that the hostile environment policy has achieved its aim, the harm to individuals has been very real, making it more difficult or impossible to access medical help, jobs, housing, or justice. The policy has been implemented through a wide array of harsh and often inhumane practices, including invasive surveillance and control measures.

One of these measures consists in tracking migrants released from immigration detention through GPS ankle tags, which monitor their GPS location every minute, 24/7. Portrayed as a way to prevent migrants absconding or breaching their bail conditions, the GPS tagging scheme also enables the Home Office to use location data to make substantive decisions on individual asylum and immigration applications. GPS (short for Global Positioning System) was a revolutionary technology that we could not possibly imagine living without nowadays - and is central to many day-to-day and essential human operations such as managing traffic, finding our way around, or emergency disaster relief. But GPS can also be a powerful surveillance tool, increasingly used to monitor and control migration flows, and the people who form part of them.

The deployment of GPS tags has alarmed a number of human rights organisations, sparking complaints by PI and a number of claims filed by tagged individuals against the Home Office for violations of their fundamental rights. Originally confined to cohorts of "very high harm offenders", the Home Office has now rolled out GPS tags to people who arrive to the UK by “unnecessary and dangerous routes”, via an expansion pilot published in June 2022. This is cruel, damaging and unnecessary.

Five companies lie at the heart of the UK’s GPS tagging system: Capita, G4S, Airbus, Telefonica and Buddi. It’s a complex entanglement of private third party responsibilities, with Capita as a core actor.

We have contacted all companies mentioned in this report to give them an opportunity to respond. Responses from Capita, G4S and Telefonica are attached at the bottom of this piece. Airbus and Buddi did not respond.

Such heavy reliance on companies is emblematic of the global rise in privatisation of migration control and policing, whereby authorities increasingly deliver public functions through tools designed and pushed by private actors, through public-private surveillance partnerships. In this piece we seek to expose and analyse the roles that these five companies play in the UK's GPS tagging scheme, and call on them to reconsider their involvement in a fundamentally inhumane practice accused of breaching data protection and human rights laws. Whether it is through implementing safeguards or terminating their contracts, private actors cannot keep on profiting from harmful and discriminatory surveillance schemes.

Capita

Capita plc is a large “consulting, transformation and digital services business” operating mainly in the UK, with roughly half of its revenue coming from services provided to the private sector and half from services provided to the public sector (see its 2021 Annual Report). Its key clients include central government departments such as the Ministry of Defence or Transport for London, as well as local government authorities such as county councils. With 53,330 employees and £3.2bn revenue in 2021, it claims to be the “number one strategic supplier of business process services (BPS) and technology to the UK Government”, and the UK’s “leading customer experience business with a blue chip client base

Capita is contracted by the Ministry of Justice to deliver the wider GPS tagging scheme set up by Her Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service (HMPPS), serving both the criminal justice sector and immigration enforcement. The company was awarded in 2014 a 6-year contract valued at £229,000,000, renewed in 2021 for a further 3 years, for £114,000,000.

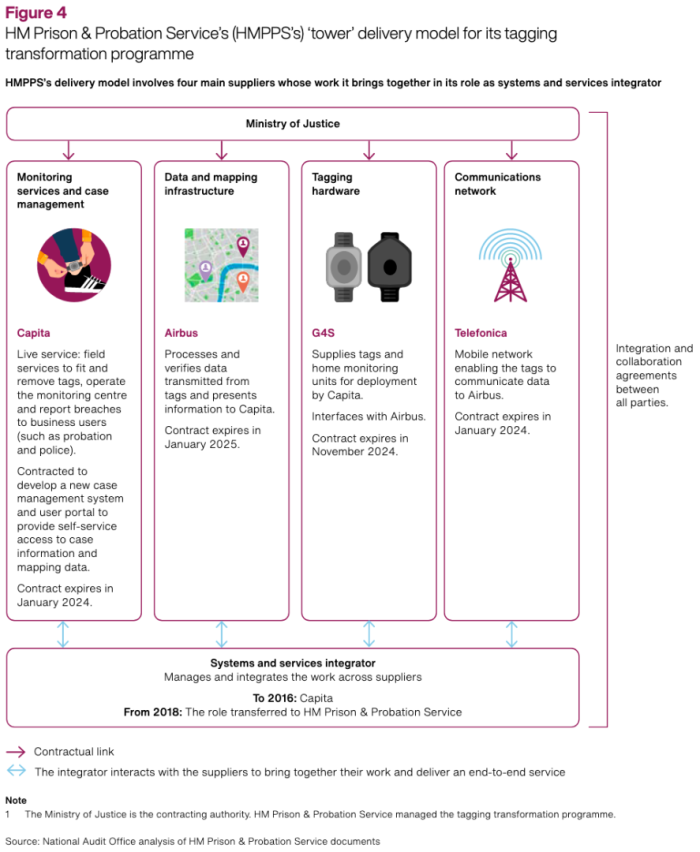

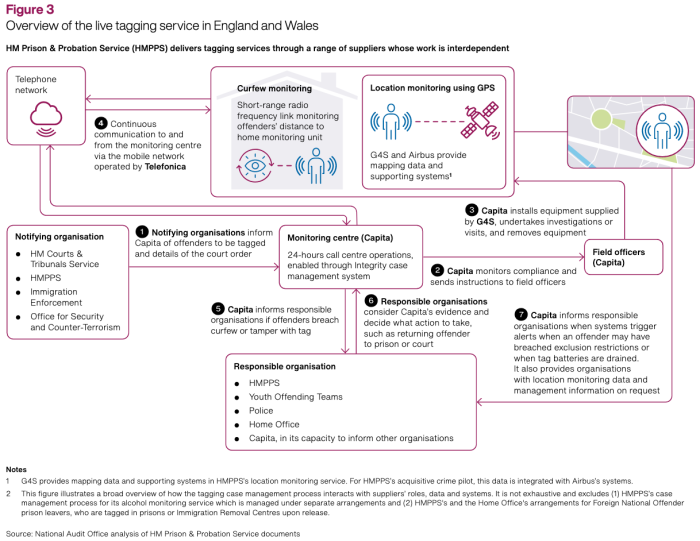

Capita’s role in the UK’s GPS tagging system has been central since 2014 and still is – it effectively runs “Electronic Monitoring Services” (EMS), the service with which tagged individuals have to interact, and is the scheme’s data gatekeeper. This is evident in the below graph from the National Audit Office (NAO), which performed a damning review of electronic monitoring in the UK.

According to the NAO report, Capita’s functions include:

- Fitting tags to individuals

- Undertaking investigations or visits

- Monitoring tagged individuals’ location

- Relaying evidence of breaches or tag tampering to the Home Office

- Providing location monitoring data and management information on request

- Running the 24-hour live monitoring call centre that monitors compliance and sends instructions to Capita’s field officers

According to the same report, the collaboration between Capita and HMPPS hasn’t been smooth sailing. Until 2018, Capita acted as systems and services integrator, but this role was handed back to HMPPS. Delays in the development of a new case management system and “a breakdown in trust and collaboration between HMPPS and Capita” led to a number of disputes and a decision to terminate the project for the new case management system. Capita ended up paying a total of £22.8m in compensation to HMPPS, while HMPPS paid £6.5m to Capita for its partial delivery of services under the contract.

Capita is not at its first controversy around its government contracts, with a number of incidents linked to poor data protection practices. In 2018, a system it had deployed to thousands of UK schools corrupted pupils’ records and linked them with incorrect contact details, leading the UK’s data protection authority (ICO) to make enquiries. In another instance of data mismanagement, in 2013 migrants legally living in the UK received emails and text messages from Capita wrongly informing them that they had to leave the country, after Capita had been contracted to track down 174,000 "illegal" immigrants. Its management of personal independence payments for the seriously ill and the disabled on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) was accused of leading to such long assessment waiting times that “in some cases people with terminal conditions have died before receiving a penny.”

The consequences of poor data protection are particularly high when dealing with highly intrusive and sensitive data such as live location data, and with the data of individuals in highly vulnerable positions. While such concerns would exist with any data processor, calling for heightened safeguards and utmost care, Capita’s track record is not particularly reassuring. The documentation (impact assessments, contracts, policy guidance) around the Home Office’s GPS tagging scheme also provides very little comfort as to the quality and robustness of data protection safeguards in place. We’ve outlined and formally raised these concerns in our complaint to the ICO.

Capita itself admits that GPS location can be inaccurate or hard to read: “Tracking offenders who have been ordered to wear ankle tags is more complicated than it seems. […] While a GPS tag captures all of a person’s movements (much like a wearable fitness device), people don’t generally move in straight lines. Human behaviour means we tend to frequent the same places often, so people tend to cross and recross their paths several times. This means it can be difficult to ‘untangle’ location data and determine where a person is at a specific time.” When this data is used to make life-changing decisions about someone, such as whether to re-detain them, deport them, or refuse their immigration application, the stakes are simply too high to rely on technology without substantive safeguards.

Meanwhile, Capita prides itself on being a “responsible business”, aware of "systemic racism and discrimination". While they highlight stories of tagging technology helping to arrest known criminal offenders, we haven’t found anything on their website boasting about their tagging of asylum seekers. To them, electronic monitoring delivers “better outcomes for both society and subjects, by giving low risk offenders the chance to continue in employment, targeting reoffending behaviour and keeping families together.” This portrayal of electronic monitoring as a humane alternative to detention ignores the well-documented mental and physical health impacts suffered by tagged people, the disproportionate effect it has on racialised communities, and obliviates the fact that tags are used for immigration enforcement as an administrative measure, not a criminal justice one.

G4S

G4S is the largest security company in the world in terms of revenue (over £7bn in revenue in 2019), employing over 490,000 people in 2020 (see their 2020 annual report), with subsidiaries around the world - in Slovenia, Israel, Angola, Bahrein, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Yemen, Papua New Guinea, China, Angola, and many other countries. G4S’s services include everything from event security, facilities management, risk management, security guards, to monitoring technology. In the UK immigration GPS tagging system, they provide, quite simply, the ankle tags.

After providing radio frequency tags and home monitoring units for years, G4S "innovated" and introduced GPS tags. As often, the UK was an “early adopter of the technology” - contributing to its “success” hailed as a “real accomplishment”. Just like Capita, G4S considers that these innovations “can only be good for victims, society and offenders themselves”. Here we have a textbook case of technosolutionism, “a way of understanding the world that assigns priority to engineered solutions to human problems. […] In the rush to embrace immediate technological fixes, its advocates often ignore likely long-term effects and unintended consequences.” G4S was awarded a contract valued between £29,000,000 and £53,000,000 in 2018 (for a contract period of 4 years), as well as a £22,000,000 contract in May 2022 (for a contract period of less than 2 years).

G4S was initially considered as a supplier to deliver “non-fitted devices”, i.e. smartwatches also recording 24/7 location, but requiring multiple daily scans of people’s biometric data. 11 months after deciding to pursue G4S’ solution, the Home Office learned that the operating system used by the devices did not meet Government Cyber Security Standards (NAO report, p.51). Eventually the Home Office sourced an “alternative option” provided by Buddi, to which we come below.

Airbus

A French company of 130,000 employees, Airbus presents itself as “the largest aeronautics and space company in Europe and a worldwide leader”. It’s no surprise that their name figures in a system reliant on GPS, fundamentally a satellite-enabled technology.

Airbus provides “data and mapping infrastructure” for the GPS tagging system, whereby it “processes and verifies data transmitted from tags and presents information to Capita” (NAO report, p.23). This is part of Airbus’ Intelligence offering, “Delivering value from Satellite Imagery in our digitally connected world”. Under this offering Airbus caters to a number of industries, helping “decision makers to increase security, optimise mission planning, improve management of resources and protect our environment.” Airbus was awarded in 2019 a contract valued at £10,400,000, running from April 2018 to May 2021.

Airbus is also involved in HMPPS’s “acquisitive crime pilot”, which can impose location monitoring as a licence condition for offenders convicted of theft, robbery or burglary offences. According to the NAO report, “[u]sing software developed by Airbus, HMPPS successfully rolled out an innovative tool which automatically compares offenders’ locations with police crime data, producing alerts when there is a potential match.” Airbus therefore provides services above and beyond mere data mapping, albeit not for the Home Office use of the GPS tagging scheme. We know from previous experience however that a technology tested and deployed in one context is frequently repurposed in others, in what is commonly called "function creep". We worry that the Home Office may later on be interested in using this software to further expand its surveillance and control of people released from immigration detention.

Telefonica

The last piece of the puzzle in the UK’s GPS tagging infrastructure is Telefonica, a global telecommunications company. Its services in the UK are offered under the O2 commercial brand - Telefonica UK Limited is the subsidiary of O2 Holdings Limited, and the parent company of giffgaff Limited.

Telefonica runs the mobile network that enables the GPS tags to communicate data to Airbus. It was awarded a contract for £3,200,000 in 2019, and another that expires in 2024 (see NAO report p.22) - which may be a contract for “Provison Mobile Devices, Voice, SMS text and Data Services to Ministry of Justice” for £7,950,000, however we do not have confirmation of this.

Buddi

In May 2022, the Ministry of Justice contracted with Buddi Limited for the provision of “Non-Fitted Devices” (“NFDs”) at a cost of £6,020,000 (for May 2022 to December 2023). NFDs were also known in earlier policy documents and DPIAs as “smartwatches”, when the plan was to roll out wristband-like devices with biometric facial recognition. The latest Immigration bail guidance, however, refers to a device that “fits in the palm of the hand - in addition to recording trail data, it can take fingerprints and will give a sound and vibrate alert to notify the person that their biometrics must be submitted - the device reads the fingerprint and compares this to the fingerprint captured when the device was issued - although the device is not fitted to the person, they are required to carry the device with them - requests for fingerprints are made on a random basis several times throughout the day to verify that the device is being carried as required - this requirement must be included within the person’s bail conditions”.

NFDs are hailed in the Buddi contract as a “more proportionate” way of monitoring people over extended periods of time than fitted tags. While lifting the weight of a non-removeable tag can be laudable, having to subject to multiple random biometric checks a day adds a layer of stress and anxiety and creates another type and level of intrusiveness. The combination of “innovative” biometric technologies with existing GPS tracking is just another step in building the total surveillance of migrants.

If you were to visit Buddi's website, you’d see no reference to their products for migrants being tracked by governments - the company markets itself as selling personal alarm wristbands for the elderly. But further digging revealed that the company’s most profitable revenue stream is the criminal justice system in the UK and abroad - it represents 98% of its revenue, compared to only 2% for the elderly care market. According to the 2021 annual report of Big Technologies PLC group - Buddi’s parent company - Buddi entered the criminal justice market in 2010, following a pilot with a UK police force, which had been using the Buddi products to “safely support victims of domestic violence, victim protection and witness protection”.

In their public statements, Buddi seem committed to their products improving the criminal justice system: “our products facilitate a shift towards rehabilitative community-based sentencing which reduces recidivism and keeps communities safer”, writes Simon Collins, Non-Executive Chair at Buddi in the Big Technologies Plc 2021 annual report. But electronic monitoring is now known to constitute a net-widening of interventions rather than a real alternative to detention, with very real mental heal impacts on tagged individuals.

For a deeper dive into Buddi, read our article Buddi Limited - Immigration Enforcement's favourite tracking buddy.

A future for migrant tracking?

Is all this taxpayer money going to private companies worth it? Not according to the National Audit Office, and it seems the government has known this for a while: “The lack of evidence for the efficacy of tagging is a long-standing issue and HMPPS acknowledges that the evidence base remains weak. In 2006, the Committee of Public Accounts recommended that government should establish how tagging affects reoffending. However, HMPPS has yet to overcome data availability and quality issues […] and is therefore currently heavily reliant on anecdotal information.”

The Public Accounts Committee has also issued a damning review of electronic monitoring in criminal justice, claiming that “The Ministry and HMPPS still do not know what works and for who, and whether tagging reduces reoffending. HMPPS has committed to improving access to data and evaluating its new tagging expansion projects, but appears unambitious about the level of insight that it expects to achieve.”

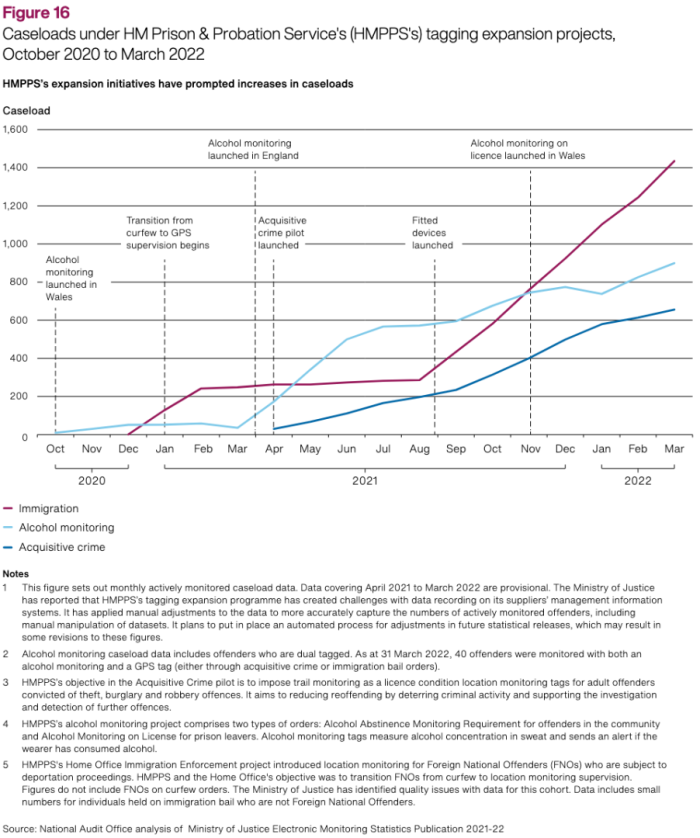

Despite the lack of evidence for the usefulness of tagging, the government is pressing ahead: “There is strong policy ambition to expand the scale and scope of electronic monitoring further across the criminal justice system. In its most recent business case seeking approval for its plans from HM Treasury, HMPPS presented projections formulated for its 2021 Spending Review bid. It estimated an additional 5,000 cases on top of its routine caseload this year, rising to a peak of around 7,900 in 2024-25” (NAO report, p.56). The expansion of GPS tagging for Immigration Enforcement has recently contributed to the exponential increase in numbers.

When people’s human rights and mental health are at stake, we’d expect the Home Office to be able to show that GPS tracking migrants 24/7 is useful, necessary and proportionate. We’re still waiting, although we know it can never be.

What we're doing

We're asking these companies to stop profiting from the UK's hostile environment, to uphold their responsible business values and to better scrutinise the human rights implications of their partnerships with governments.

While our complaints against the government's GPS tagging policy are being investigated, we're calling on Capita to stop enabling and profiting from this hostile policy.