Business As Usual? How Western Data Analytics Companies Are Peddling Fear In Fragile Democracies

This post was written by PI Policy Officer Lucy Purdon.

In 1956, US Presidential hopeful Adlai Stevenson remarked that the hardest part of any political campaign is how to win without proving you are unworthy of winning. Political campaigning has always been a messy affair and now the online space is where elections are truly won and lost. Highly targeted campaign messages and adverts flood online searches and social media feeds. Click, share, repeat; this is what political engagement looks like now. The question of whether the use of data analytics to target voters interferes with democracy is currently being investigated in the UK and the USA.

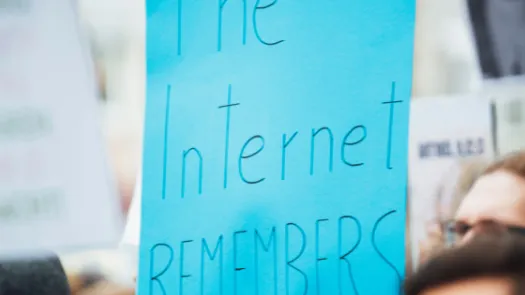

Particularly in countries where there is history of political violence, campaigning based on data analytics is untested ground fraught with great risk. This is not about foreign governments spreading messages on social media intended to disrupt another country’s election. That’s another story. This is about the powerful and opaque corporate ecosystem behind targeted online political advertising. This is about data analytics and digital media firms, employed directly by political parties contesting elections, working directly with online platforms to craft micro-targeted political messages. But exactly who they work for, what they do and how they do it is often a guarded secret.

A new investigation by Privacy International analyses several online political campaigns for Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta in the 2017 Presidential elections. It reveals that Harris Media, a US digital media firm, was responsible for two controversial campaigns, The Real Raila and Uhuru For Us, produced on behalf of the Kenyan President. The adverts played heavily on Kenya’s violent past elections and contained coded political language designed to provoke fear.

Like Harris Media, UK data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica also discreetly worked for the President in the same time period. The extent of their role in the 2017 election is unclear, and whether they collected sensitive data of Kenyans.

We only need to look to Kenya’s election history to understand why these activities are problematic. The 2007/2008 election resulted in violence that killed over 1,000 people and displaced over 600,000. The 2013 election was peaceful, but marked the rise of online ‘hate speech’ that exploited ethnic tensions. The 2017 election result was annulled and rerun amidst great tension and loss of life, while targeted online political adverts played on national fears of further violence.

There are two major concerns, the first of which is the secrecy surrounding online campaigns. Kenyan electoral laws do not clearly require candidates to endorse campaigns or adverts they have funded. The companies involved are not forthcoming about their role. It is essential for political campaigns to be run in a transparent and accountable way, particularly when the stakes are this high in a country like Kenya. Currently, targeted online political advertising is neither.

It is well known that Facebook’s advertising revenue is so lucrative because of the ability to offer targeted advertising, based on user information like age, location and interests. This has proved so successful that political parties want in. In the same way that online advertising targets people based on personality and mood to ultimately sell products, political parties persuade you to buy what they are selling come election time.

Additional information is inferred from your data, like your preferred candidate, your personality or your emotional state, in a specially created profile used to assist targeting. In Kenya, we do not know how targeting was done, and if profiles included tribal affiliation or other politically sensitive criteria.

The second major concern is that many countries still lack sufficient laws to safeguard data protection and privacy affected by this level of data generation and processing. Kenya does not have a comprehensive data protection law which would compel any entity — public or private — to respect fundamental data protection standards. This includes providing the legal grounds for collecting data and obtaining informed consent from the individual, in particular for the processing of sensitive personal data.

With limited legal protections for personal data, there will be consequences, as individuals are left vulnerable to excessive data being collected on them without their consent and used in ways they are not aware of. When companies collect data in countries with insufficient legislation and share it with third parties it is unclear what standards they, and these third parties, are holding themselves to, if any.

While data driven campaigns are not new, their use in countries like Kenya is. In countries with a history of political violence, it should not be “business as usual”. Ethnicity in Kenya has become politicised. It is still a sensitive issue and elections are a time of heightened tension. Therefore, at the very least, companies in this ecosystem must be transparent about their role in online political campaigns. Political parties need stricter rules on declaring campaigns they have funded and therefore endorsed. When it is not transparent who has funded or created campaign adverts, there is no accountability.

Regardless of political affiliation, the world of targeted political advertising needs dragging out of the shadows. Any campaign run on confusion, suspicion and fear instead of transparency and accountability is surely a political campaign that proves unworthy of winning.