Addressing The Right To Privacy At The United Nations

What do Egypt, Kenya, Turkey, Guinea, and Sweden have in common? Despite having a Constitutional right to privacy, they are adopting and enforcing policies that directly challenge this human right.

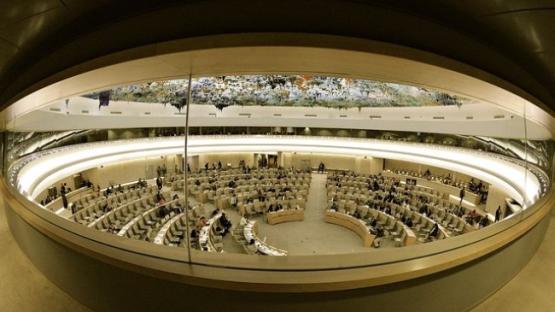

These states are also up for a Universal Periodic Review this year before the United Nations Human Rights Council. UPRs are a mechanism within the Council aimed at improving the human rights situation in all countries and address human rights violations wherever they occur.

Despite having provided a valuable space for civil society to engage in the review of human rights policies and practices, historically the right to privacy has remained largely absent within the UPR mechanism.

In order to address this flaw, Privacy International has been engaging since 2013 in the UPR through the submission of joint stakeholder reports, in partnership with leading national civil society organisations and experts. In 2013, Privacy International submitted join stakeholder reports on Mexico, China and Senegal. This year, we submitted reports on Egypt, Kenya, Guinea, Sweden, and Turkey, and will make a submission on the US and Belgium later in the year. We hope that the Human Rights Council within the UPR process will address the privacy concerns raised by Privacy International and its partners of the need to protect privacy rights in these countries.

While situations differed across the countries, we have identified three main issues when analysing the threats to the right to privacy: Monitoring and surveillance of communications, compulsory SIM card registration, and the absence of data protection laws.

Monitoring and Surveillance of Communications

Kenya

In Kenya, new laws, such as the Kenya Information and Communications (Amendment) Act 2013 and the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2012 and programmes have emerged for the monitoring and surveillance of communications, with some evidence of the deployment of highly intrusive surveillance technologies.

There have been recent findings confirming the purchase and deployment of mass surveillance technologies in some of these countries. In January 2013, the Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto published a research brief, Planet Blue Coat: Mapping Global Censorship and Surveillance Tools, in which they reported they had discovered three Blue Coat PacketShaper installations in various countries including Kenya and Turkey.

Despite Kenya’s efforts to strengthen and embed privacy protections in its constitutional and legislative framework, there are concerns over recently adopted surveillance policies. Following several incidents of terrorism over the past few decades, the government in 2012 introduced a surveillance programme called the Network and Early Warning systems (NEWS). After the scarring Westgate mall attacks in September 2013, authorities announced the building of the Integrated Public Safety Communication and Surveillance System, which would include a large CCTV monitoring systems. And whilst the project is currently on hold following a procurement scandal, the intentions of the government to deploy such a system remains worrying.

Further, it was recently revealed that the NSA has been running a programme known as MYSTIC, which secretly monitors the telecommunications systems of several countries including Kenya, where the system is known as DUSKPALLET. While the extent of the role of the government is yet unknown, such mass untargeted interception of communications constitutes a direct interference with the right to privacy because of their unlawful and disproportionate nature.

Turkey

In Turkey, the chilling effects on freedom of expression are widespread, as the Turkish government has for several years implemented restrictions on internet freedom and the public believes that the monitoring of mobile communications is common. While Turkey will be the host of the Internet Governance Forum in September 2014, recent actions by the government have failed to show its commitment to respect and uphold the value and principle of the internet as a free, open and safe for citizens to engage.

In February this year, the government amended a censorship law providing the Turkish Telecommunications Authority (TIB) with the power to request the removal of content from websites, in some cases without having first obtained a court order. The amendment also extended the number of internet providers required to store records of internet activity for two years.

In addition, in April 2014, Turkey adopted a new law giving the National Intelligence Agency broader powers to amass private data, documents, and information about individuals in all forms without the need for a court order. Human rights groups have denounced the new law as it undermines the right to privacy by permitting unfettered access to data without judicial oversight or review.

Egypt

Over in Egypt, recently leaked documents from the Egyptian Ministry of Interior revealed that the government of Egypt was trying to acquire mass surveillance equipment with the aim of deploying a programme called, “Social Networks Security Hazard Monitoring system”. This news is of extreme concern for human rights, particularly internet privacy and freedom of expression, given the years-long running crackdown against demonstrators, political dissidents, journalists, and human rights. Steps are being taken to establish democratic structures and processes in Egypt, and such surveillance initiative counteract all efforts being deployed.

There has also been evidence of the use of communication surveillance and monitoring software sold by Hacking Team and Gamma International.

Sweden

In Sweden, the recent revelations emerging from documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden have indicated close connections and collaboration between Sweden’s National Defence Radio Establishment(FRA) and the NSA in mass surveillance practices.

Other areas of concern in Sweden have been the export of surveillance technologies to repressive regimes, and TeliSonora, a partially state-owned Swedish telecommunications company, providing other States access to communications flowing through its network.

Compulsory SIM Card Registration

Turkey, Egypt, Guinea and Kenya all have mandatory SIM card registration, which require all users to present national identification documents to register their SIM cards. SIM registration undermines the ability of users to communicate anonymously and disproportionately disadvantages the most marginalised groups. It can have a discriminatory effect by excluding users from accessing mobile networks, and facilities surveillance by making tracking and monitoring of users easier for law enforcement authorities.

This is a concern for all citizens, but particularly for those targeted by the government’s communication and monitoring programmes such as political activists, human rights defenders and journalists. All these groups increasingly rely on such means of communication to operate, mobilise and record information.

In Kenya, where through practices and law civil society organisations are already under threat and increasing government control, mandatory SIM registration is a particular concern. Further, those who don’t comply are hit with extremely harsh penalties. Under Section 27C (4) Kenya Information and Communications (Amendment) Act 2013, it is a criminal offence to no register you SIM card, and not doing so lands you a fine (< KES 100,000/USD 1,150) and/or imprisonment (less than six months).

Absence of Data Protection Laws

Despite most countries have Constitutional protections of privacy and personal data, 101 countries in the world have domestic data protectionlegislation. The lack of domestic legislation facilitates rights-limiting practices when it comes to data protection, as there is no regulation or control of activities of public and private entities that entail the collection, processing and storage of personal data. This raises concern as to the safety and security of the data stored, fails to provide individuals information on their right to privacy, and denies people necessary protection of their personal data or legal recourse in case of violations by an independent authority.

In Kenya, a Data Protection Bill has been in the works since 2012, and has been forwarded to the Attorney General for publication. The Bill was expected to be presented in Parliament by the end of May 2014, but this has not yet happened.

The absence of such legislation in Kenya is worrying. The Kenyan government has been embracing technology to address socio-economic problems, for example through the use of mobile cash transfers in the deployment of social protection programmes. Whilst not discrediting the benefits that emerge from such programmes, the legal void in which they operate raises privacy concerns. A strong data protection bill must be passed immediately to protect Kenyans while these programmes are advanced.

In Turkey, a packet of Constitutional amendments in 2010 included an explicit recognition of the right to data protection to the Constitution. However, this constitutional protection for the right has not been appropriately supported by domestic legislation. As such, the absence of data protection laws has permitted rights-limiting practices. For instance, the Ministry of Education sold the data of 17 million students to a mobile operator and Turkey’s largest internet service provider installed deep packet inspection technology to create profiles of an individual’s online activities to sell to advertisers.

Both Guinea and Egypt lack data protection legislation, and no bills have yet been drafted to address this absence. It is essential that these countries adopt data protection laws to ensure the protection of the right to privacy of citizens in accordance with international human rights law and Constitutional rights.