New court judgment finds UK surveillance agencies collected everyone’s communications data unlawfully and in secret, for over a decade

Key points

- Bulk Communications Data (BCD) collection, commenced in March 1998, unlawful until November 2015

- Bulk Personal Datasets regime (BPD), commenced c.2006, unlawful until March 2015

- Everyone’s communications data collected unlawfully, in secret and without adequate safeguards until November 2015

- We maintain that even post 2015, bulk surveillance powers are not lawful

- As the Investigatory Powers Bill is set to become law within weeks, we argue that the authorisation and oversight regime that was left wanting pre 2015 remains deeply inadequate.

- Judgment will be here shortly: http://www.ipt-uk.com/judgments.asp

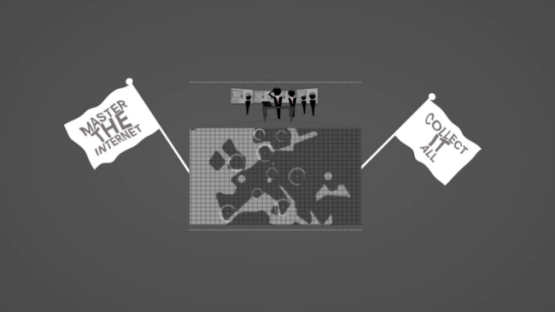

In a highly significant judgment released today, The Investigatory Powers Tribunal has found that the UK’s intelligence agencies were secretly and unlawfully collecting bulk data on people in the UK without adequate safeguards or supervision for over a decade. This is one of the most significant indictments of the secret use of the Government’s mass surveillance powers since Edward Snowden first began exposing the extent of US and UK spying in 2013.

The Tribunal, which is tasked with hearing complaints against the security and intelligence services, concluded that the two regimes, which permitted the collection of vast amounts of communications data (Bulk Communications Data) and large datasets with personal information (Bulk Personal Datasets), were unlawful for over a decade.

The case exposed inadequate safeguards against abuse, including warnings to staff not to use the databases created to house these vast collections of data to search for and/or access information ‘about other members of staff, neighbours, friends, acquaintances, family members and public figures’. Internal oversight failed, with highly sensitive databases treated like Facebook to check on birthdays, and very worryingly on family members for ‘personal reasons’.

The Tribunal ruled that “we are not satisfied that … there can be said to have been an adequate oversight of the BCD system, until after July 2015” with “no Codes of Practice relating to either BCD or BPD or anything approximating to them.” There was no statutory oversight of BPD prior to March 2015 and there has never been any statutory oversight of BCD.

Noting the highly secretive nature of the illegal BCD regime, the Tribunal ruled “it seems difficult to conclude that the use of BCD was foreseeable by the public when it was not explained to Parliament”.

The judgment does not specify whether the unlawfully obtained, sensitive personal data will be deleted.

Despite the Tribunal finding the regimes to be lawful after their respective “avowals” in 2015, Privacy International argues that they remain inadequate. There is no requirement for judicial or independent authorisation. Supervision by a member of the executive (i.e. a Government Minister) does not provide the necessary guarantees that surveillance operations that could impact on millions of people are necessary and proportionate. There is no procedure for notifying victims of any use or misuse of bulk communication data so they can seek an appropriate remedy. Entire databases of BCD and BPDs can be shared with foreign partners, ‘industry partners’ and other Government agencies. And the Tribunal has not assessed the necessity and proportionality of gathering such intrusive data about UK residents in bulk.

Mark Scott of Bhatt Murphy Solicitors, instructed by Privacy International in the legal challenge, said:

“This judgment confirms that for over a decade UK security services unlawfully concealed both the extent of their surveillance capabilities and that innocent people across the country have been spied upon.”

Millie Graham Wood, Legal Officer at Privacy International said:

“Today’s judgment is a long overdue indictment of UK surveillance agencies riding roughshod over our democracy and secretly spying on a massive scale. There are huge risks associated with the use of bulk communications data. It facilitates the almost instantaneous cataloguing of entire populations’ personal data. It is unacceptable that it is only through litigation by a charity that we have learnt the extent of these powers and how they are used. The public and Parliament deserve an explanation as to why everyone’s data was collected for over a decade without oversight in place and confirmation that unlawfully obtained personal data will be destroyed.”

- Ends -

Notes to editors

- IPT finds bulk powers (BCD and BPD) to be neither accessible nor foreseeable during the relevant period.

- The IPT holds the Bulk Communications Data (BCD) regime (the where, when and what of communications), which commenced in 1998, did not comply with Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights until 4th November 2015

- The IPT holds the Bulk Personal Datasets (BPD) regime (which enables intelligence agencies to requisition databases of information that might include medical records, tax records, electoral register information and virtually any other database of information held by companies, Government departments, charities), which has been in operation for around 10 years, did not comply with Article 8 until 12th March 2015.

- In 2015 the Government admitted it had been using an obscure and vague clause in a piece of legislation from 1984 to obtain bulk communications data (BCD). A legal challenge brought by Privacy International in June 2015 forced the Government and intelligence agencies to disclose practices which have now been found unlawful, which had been kept hidden not only from the public but also from Parliament. The Tribunal noted that despite ‘several opportunities’ over the many years that these powers were used, ‘the government of the day did not avow the use of section 94’ of the 1984 Telecommunications Act.

- BPD and BCD are intrusive and comprehensive. Current BCD collection includes location information and call data for everyone’s mobile telephones in the UK for one year.

- BCD is the who, when, where, and how of a communication. It includes, but is not limited to, visited websites, email contacts, to whom and where and when an email is sent, map searches, GPS location and information about every device connected to every Wifi network. BCD can provide vast knowledge about individuals.

- BPDs are large datasets that are incorporated into ‘analytical systems’. They contain considerable volumes of personal data about individuals, the majority of whom are unlikely to be of intelligence interest. They include biographical details, commercial and financial activities, communications and travel as well as BCD. BPDs contain the content of legally privileged communications (David Anderson QC para 2.84 Report of the Bulk Powers Review).

- The claim concerned the acquisition, use, retention, disclosure, storage and deletion by GCHQ, SIS and the Security Service of Bulk Communications Data (BCD) obtained under section 94 of the Telecommunications Act 1984 and Bulk Personal Datasets (BPDs) obtained under a variety of legal powers.

- These revelations come as a result of Privacy International’s litigation. Indeed, even Parliamentary debates about the Investigatory Powers Bill over the last year, which were supposed to have been the Government’s opportunity to come clean about the surveillance powers it has and the new powers it wants, have barely touched on the BPD and BCD regimes, which give the Government deeply intrusive powers to reach into every aspect of our lives.