Ethiopia expands surveillance capacity with German tech via Lebanon

German surveillance technology company Trovicor played a central role in expanding the Ethiopian government's communications surveillance capacities, according to a joint investigation by Privacy International and netzpolitik.org.

The company, formerly part of Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN), provided equipment to Ethiopia's National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) in 2011 and offered to massively expand the government's ability to intercept and store internet protocol (IP) traffic across the national telecommunications backbone. Trovicor's proposal was to double the government's internet surveillance capacity: two years' worth of data intercepted from Ethiopian networks would be stored.

Trovicor's predecessor in intelligence solutions, Siemens Pte worked closely with its British partner Gamma Group International via an offshore company in Lebanon to expand lawful interception in the east African country. Gamma Group's highly intrusive FinFisher malware suite was used to target Ethiopian dissidents. Forensic traces of FinFisher malware have also been traced back to one of Gamma's Lebanese operations.

Together, the companies and their Lebanese offshore subsidiaries helped one of Africa's most repressive governments spy on one of its largest populations.

Backdoors to the backbone

Since 1991, Ethiopia has been governed by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPDRF), a coalition of ethnically-based political parties that has severely restricted freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. Police has and security forces have been accused of torture. The National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), an Ethiopian intelligence agency has used intercepted communications data to identify and punish targets it perceives as opposed to the government. Journalists, activists and average citizens widely assume that their communications are extensively monitored. Phone records and transcripts have also been used to extract confessions under torture, according to Human Rights Watch.

The Information Network Security Agency (INSA), created in 2011, consolidated and extended the state's surveillance and censorship of internet traffic. It is reported to have used 'deep packet inspection' which allows for the inspection and rerouting of internet traffic as it passes an inspection point and fulfils certain criteria defined by the inspecting agent. In 2012, it blocked access to the anonymous browsing service Tor, further restricting safe spaces for communication. INSA is alleged to be the agency responsible for using offensive malware from Italy-based Hacking Team in 2013 and 2014 to target journalists.

Ethio Telecom runs the country's phone and internet services as a state-owned monopoly. In 2010, the Ethiopian government contracted France Telecom to manage the company, changed its former name and embarked on a serious expansion of the country's infrastructure. While good news for rural Ethiopians who have much less access to quality communications services, the government also expanded its surveillance capacities to match.

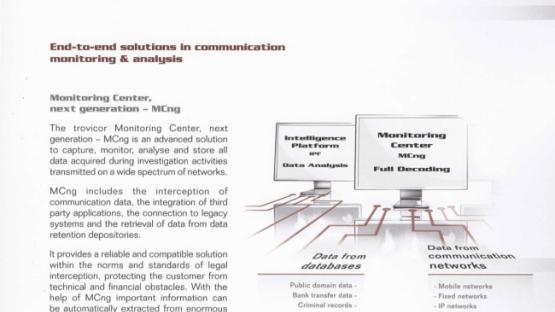

Trovicor was central to this expansion plan. The Munich-headquartered company sells monitoring centres to government and law enforcement clients worldwide to capture, monitor, analyse and store all data acquired during investigation activities transmitted on a wide spectrum of networks. Trovicor technicians work to integrate interception gateways provided by Trovicor or partner companies into network infrastructure of service providers to funnel communications data to the monitoring centres.

Trovicor continues the work of Nokia Siemens Network (NSN), a Helsinki-based joint venture of German conglomerate Siemens AG and Finnish telecoms company Nokia. In 2009, NSN sold its intelligence wing 'Siemens Intelligence Solutions' to Perusa Partners Fund 1 LP, a private investment firm, amid controversy that it supplied of surveillance systems to Iran. Perusa renamed its new acquisition 'Trovicor.'

In January 2010, two representatives of the company presented an Ethiopian customer with a detailed operational plan to massively expand the government's capacity to monitor IP traffic, according to a document obtained by netzpolitik.org.

Ethiopia's fiber optic backbone carries the country's mobile and internet traffic. Signals travel across Ethiopia through many different traffic routers including local and regional routers and international gateways. IP traffic originating or travelling abroad, for example to and from Gmail's US-based storage servers, would pass through internet gateways at three sites. In 2010, the existing fiber optic cable routes radiated from Addis Abeba along the country's roadways to key towns including Gonder and the Sudan border to the northwest, Mek'ele to the North, Nekemte to the West, Awassa to the south, Dire Dawa to the East and out to the Red Sea via Djibouti. That year, the government planned to add 37 new fiber routes covering a distance of around 10,000 kilometers and reaching further into rural Ethiopia.

The government required massively expanded powers to intercept IP traffic across the new and existing cables. The government was to add new local-level 'edge routers' (ER) to 25 new locations. At each of these ER, Trovicor proposed, the company would install its own next generation network (NGN) taps. These taps would not interfere with the transmission of the signal. Instead, they would also transmit traffic from the ER to a Trovicor aggregation switch that would transmit the signal to the government's monitoring centre – provided by Trovicor. The monitoring centre would require data from all 25 new aggregation switches to be provided to it on a single 10GbE link.

The government would double its storage and archiving capacity under Trovicor's plan. Two years' worth of data transmitted across Ethiopian networks could now be analysed. A total of 3 terabytes could be stored online and actively queried by monitoring centre analysts; a further 28 terabytes of material could be archived.

With Trovicor's plan, analysts would be able to locate a mobile caller based on his or her proximity to cell phone towers. Trovicor offered to add this geolocation capacity – a “very cheap solution in comparison to the positioning systems” – to the monitoring centre and to integrate the centre with the network architecture provided by Chinese company ZTE.

Throughout this period Ethio Telecom regularly conducted business with Nokia and Siemens companies, some of it for lawful interception, according to records obtained by Privacy International. It is not clear whether Trovicor was ultimately chosen to expand network interception capacities according to the January 2010 plan. Trovicor was, however, doing business in Ethiopia in 2011. In June 2011 the company sent a shipment to the NISS security agency from Munich to Frankfurt and onwards to Addis Abeba via an Ethiopian Airways flight, according to company records. Its exact contents are unknown. Trovicor and Siemens did not respond to requests for comment.

The Lebanese Connection

The 7th floor of Broadway Building in Beirut's fashionable Hamra district houses two surveillance technology companies – Elaman and Gamma Group, or rather, their offshore affiliates.

Headquartered in Munich, Elaman sells a range of surveillance equipment, from communications monitoring centres to specialist cameras and body-worn call interception devices. It is also a distributor and close partner of the British surveillance consortium Gamma Group. Elaman marketed FinFisher, a malware suite that allows its user to access all stored data and even to take control of the microphone and camera, before Gamma took over the promotion and leadership behind the product in the late 2000s. The Elaman-Gamma partnership had “successfully been involved over the past five years in projects and contracts worth more than 200 million euros”, according to one brochure.

Both companies provide powerful surveillance technology via Lebanon. Four joint stock companies – Elaman - German Security Solutions SAL, Gamma Group International SAL, Gamma Cyan SAL Offshore, and Cyan Engineering Services SAL – share the same registered address, above the Beirut offices of humanitarian charity Save the Children.

Siemens paid one of these companies, Gamma Group International SAL, for an “Ethiopia Lawful Interception” project sometime before July 2011. Gamma Group International SAL's business is facilitated by Nabil Imad who appears as a beneficiary on a bank account attributed to Gamma, according to information obtained by Privacy International. Lebanese law requires joint stock companies, known by the French acronym SAL, to have between three and 12 shareholders, the majority of whom must be Lebanese. Nabil 'Sami' Imad is listed as the director of both Gamma Cyan SAL and Elaman SAL while 'Sami Nabil Imad' appears as director of Gamma Group International SAL. Mohammad Farid Mattar, a lawyer representing the heir of assassinated former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri at the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, is also listed as a director of Gamma Group International SAL. The Lebanese company's only listed non-Lebanese shareholder is its chairman, Louthean John Alexander Nelson. Nelson directs Gamma Group International Ltd. Gamma Group and Mattar both declined to offer comment.

In a written response to Privacy International’s and Netzpolitik’s questions regarding the operation, a lawyer for Gamma would neither confirm nor deny the details of this report. The same lawyer, speaking on Mr. Mattar’s behalf, would neither confirm nor deny Mr. Mattar's involvement.

The “Ethiopia Lawful Interception” project could have been to integrate FinFisher into an Ethiopian Trovicor monitoring centre. Trovicor has offered to supply Gamma products to governments worldwide, including in Tajikistan in 2009. A 2010 Gamma Group newsletter celebrated a new partnership with Trovicor based on successful collaboration in joint ventures. Wikileaks has identified that Gamma employees Stephan Oelkers and Johnny Debs visited Ethiopia in 2013 and Elaman CEO Holger Rumscheidt visited in 2012.

The combination of the two companies' capabilities at the time – massive monitoring centres and the deployment of the FinFisher malware – presents a very concerning capability in the hands of a repressive government. FinFisher was used to target members of the Ethiopian political movement, Ginbot 7. Researchers at the Citizen Lab, a technology laboratory based in Canada, analyzed malware samples and determined that a FinFisher campaign originating in Ethiopia used pictures of Ginbot 7 members as bait to infect users – the corrupted files, when opened, would install the spyware onto the user's device.

FinFisher was deployed against Ethiopians living abroad as well. Tadesse Kersmo is a London-based lecturer and member of Ginbot 7. Suspecting that his device was compromised, in 2013, he submitted his computer to Privacy International which, in collaboration with a research fellow of the Citizen Lab, analysed the device and found traces of FinFisher malware. The Citizen Lab's forensic analysis of FinFisher samples obtained elsewhere have linked certificates for the samples to Cyan Engineering Services SAL. Kersmo used to use his computer to keep in touch with his friends and family and continued to advocate for democracy back in Ethiopia. With his chats and Skype calls logged, his contacts accessed, and his video and microphone remotely switched on, it was not only Kersmo that was threatened, but also every member of the movement.

Meanwhile in Germany, where Trovicor is headquartered and Gamma GmbH had an office before they transformed into FinFisher GmBH, German authorities maintain that they are unaware of either company supplying surveillance equipment to Ethiopia. After an investigation prompted by mounting evidence that German companies are leaders in the sale of surveillance technology worldwide, the German export agency said in a letter to the Bundestag that it found no records of any sale of surveillance technology to Ethiopia. However, the absence of records does not mean that no sales were made; unlike the sale of arms and other military equipment that necessitate the consideration of the human rights implications of a sale by export authorities, the sale of surveillance technology was not covered by any export regulation at the time of its export, allowing companies and their customers to trade free from any public scrutiny.

Back in Ethiopia, journalists, activists and many ordinary citizens self-censor in the face of constant government surveillance of their private communications. “We use so many code words and avoid talking directly about so many topics that often I’m not sure I know what we are really talking about” said one person who spoke with Human Rights Watch.

Thousands of kilometres away, European companies and their slightly closer Lebanese entities are responsible for these silences.