Discussion About Cyber Security In Colombia

Written by: Maria del Pilar Saenz

With a raft of recent scandals involving proven and possible abuses of surveillance systems by state institutions, there is a clear need to generate policy and practice in Colombia that promotes respect for human rights. It is necessary to keep this in mind as an emerging public policy discussion on cybersecurity led by CONPES (The National Council for Economic and Social Policy) begins in Colombia. This series of reforms will serve as the policy basis for the coming years. Discussions should start by integrating a human rights based approach, learning from the experiences of the past, recognizing the present challenges, and looking to the future to anticipate further hurdles.

Past

Perhaps abuses committed by the now extinct Administrative Department of Security (DAS, in Spanish), known in Colombia as ChuzaDAS, are the most infamous examples of illegal use of surveillance systems by the state against human rights defenders, journalists, activists and political opponents. In this shameful precedent, even the high courts of the country were tapped. After several years of investigation, the response was the dismantling of the DAS and the creation of the National Intelligence Agency. Even today, eight years later, investigations regarding individual criminal liability for the scandals are still ongoing.

However, it was the attacks carried out in 2011 by Anonymous against some state websites, and the increase in cybercrime, that were cited as the reasons for new public policy guidelines in the area of cyber security and defense contained in CONPES 3701 document.

This document recommended creating a number of institutions such as the Intersectoral Commission, embodied in the State Information Digital and National Commission created in January 2013; the Colombian Cyber Emergency Response Team (colCERT), created in June 2013; the Joint Cyber Command of the Armed Forces (ACPC, in Spanish), created in October 2012; and the Cyber Police Centre (CPC).

Besides the 2011 cyber security CONPES, the legal tools necessary for the prevention, investigation and prosecution of cybercrime was strengthened. In line with this the policy framework was strengthened, led by the Intelligence Act (Law No. 1623 of 2013), along with other laws such as the Statutory Act on Personal Data Protection, the Transparency in Access to Public Information Act, and the Decree on Legal Interception of Communications.

However, these changes made little impact in preventing abuses of surveillance systems and 2014 marked the beginning of a new scandal. The Colombian army had mounted a front operation, in the form of a security hackerspace where, besides asking young people to solve technical challenges, it apparently involved interception of the communications of negotiators attending talks with the guerilla group FARC.

This new scandal, coupled with a story about an interception of the email account of the current president and the fact that the layout plan in the 2011 CONPES had already been 90% developed according to the deputy minister of Ministry of ICT, raised the need to develop new public policy guidelines on issues of digital security. The process began in March 2014. The new CONPES draft was only released publicly in January 2016, and consultations in sectoral working groups were held the following week. The final version is yet to be published.

Present

The creation of a new digital security CONPES is an opportunity to introduce a human rights approach into the public policy discussion on cyber security. With this in mind, the current CONPES draft has made some advances. However, Karisma, the Foundation for the Freedom of the Press (FLIP, in Spanish), the Colombian Commission of Jurists (CCJ) and a handful of citizens presented comments and criticisms to the January document.

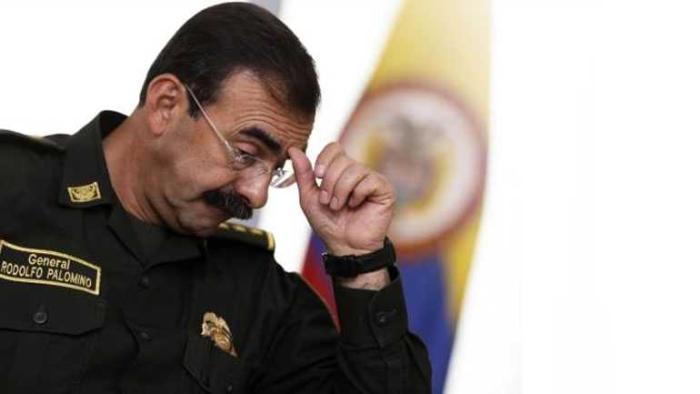

As if more evidence of the urgency of this discussion was needed, in late 2015 a new scandal was uncovered involving the possible abuse of surveillance mechanisms by some members of the police against journalists. As part of a journalistic investigation into possible prostitution, corruption and illicit enrichment involving the former director of the National Police, General Palomino, it was revealed that journalists working on the story were placed under surveillance, had their communications intercepted and were targeted with remote control software. The capacity to use these tools was denied in public statements by General Palomino. However, the complaints by journalists have led to the beginning of several investigations, including one from the Inspector General, in which Karisma was officially requested to send the original version of the Privacy International report Shadow State: Surveillance, Law and Order in Colombia.

Future

While in recent years there has been progress incorporating civil society concerns in addressing issues of cybersecurity in domestic politics while considering human rights, there are still several outstanding discussions, especially against the issue of the protection of privacy in the country.

As already noted, the absence of oversight mechanisms on intelligence and counterintelligence activities is perhaps one of the most important recurring points whenever the issue of possible reforms to the intelligence systems in Colombia is raised. However, it is not the only one.

It is a concern, as mentioned by Dejusticia in its analysis of communications surveillance in Colombia, that the definition of monitoring of the electro magnetic spectrum contained in the Intelligence Act allows for the “collection, processing, analysis and dissemination of information” to prevent and combat threats of internal or external origin to the democratic, constitutional and legal regime, and against security and national defense. Monitoring is not considered by current legislation as interception of communications and as such is not subjected to any judicial control.

Another point to consider is the data retention standard. Introduced by the Intelligence Act and developed in the Decree on Interception of Communications, communications operators are compelled to retain information about their subscribers for five years. Access to this information does not require authorities to obtain warrants.

The maintenance of an old law banning the sending of encrypted communications is another issue to be pondered. While authorities have said that this proscription does not compromise digital media encryption, it should be removed to remove any ambiguity.

Another emerging issue is the use of hacking tools by state agencies. While these tools are part of the most advanced techniques to prosecute and capture criminals, their acquisition and use is not regulated and their deeply intrusive nature urgently requires oversight of their use.

These points and additional concerns were recently submitted by Karisma, Dejusticia, FLIP and the CCJ to the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy and will certainly be topics to be developed in the near future.

Much work still remains to be done to change the current state, where vital discussions are postponed because of repeated scandals. The implementation of the new digital security policy and a possible post conflict scenario that is expected to happen after the signing of the peace process in Colombia will be an opportunity to emphasise the need to incorporate a human rights approach, as well as the respect for and protection of privacy as a fundamental part of these processes.

With the panorama of systemic threats to privacy of journalists, human rights defenders, political opponents, activists and civil society organisations, it will be imperative to have proper documentation of cases and evidence of both illegal wiretapping and use of remote hacking tools. However, the current institutions responding to digital incidents are part of the military and police structures which sometimes are the same source of threats to civil society, hence the lack of confidence in those institutions. This raises the possibility of creating separate institutions that can gather and analyse information of digital incidents and threats to civil society actors in Colombia and help them to increase their digital security.

The request by the Inspector General for the Privacy International report to be sent to him, in connection with the latest scandal, confirms that there is a real possibility of influencing, of being heard, and that civil society’s arguments and evidence are beginning to be taken into account. The challenge now is in moving forward towards a real approach to human rights.