New Documents Reveal Kenya's Worrying Attempts to Monitor the Internet

In January 2017, Kenya’s information and communication technology regulator, the Communications Authority of Kenya, announced that it was spending over 2 billion shillings (around 14 million USD) on new initiatives to monitor Kenyans’ communications and regulate their communications devices. The press lit up with claims of spying, and members of Kenya’s ICT community vowed to reject the initiatives as violating Kenyans’ constitutional rights, including the right to privacy (Article 31). Nevertheless, the Communications Authority claimed that these projects would help prevent a repeat of the post-election violence following the 2007 presidential elections.

As political tension continues to mount in the run up to next month’s presidential elections, the Kenyan government has also rushed to operationalise a cybersecurity strategy that was first articulated in 2014. But what does the development of Kenya’s cybersecurity practices practically mean for Kenyan citizens?

Privacy International was able to examine several cybersecurity initiatives, from the National Kenya Computer Incident Response Team Coordination Center (KE-CIRT/CC) to the Network Early Warning System (NEWS), to a more recent, concerning initiative – the National Intrusion Prevention and Detection System (NIPDS). This investigation is primarily based on documents provided in confidence to Privacy International. We also wrote to the Communications Authority, which did not return repeated requests for comment.

Many governments have chosen to frame cyber security as a national security issue. This ‘securitisation’ approach generally signals a government’s intention to make cyber security the domain of intelligence agencies. The Kenyan government’s existing cybersecurity initiatives share a clear emphasis on the national security framework, which is visible notably from the prominent role of the National Intelligence Service (NIS), Kenya’s primary intelligence agency and the agency with the most sophisticated signals intelligence capacity. This is particularly concerning given NIS’ routine abuse of their powers of surveillance, as detailed in a previous Privacy International investigation.

As the candidates are pledging transparency throughout the election season, clarity, too, is needed about what exactly the government’s cybersecurity initiatives mean for the voting public. This investigation is a first attempt to provide this transparency. It questions default framing of cybersecurity as equivalent to national security.

Cyber Security As National Security

Cybercrime attacks have been estimated to have cost Kenyan businesses 175 million USD in 2016. Popular mobile money platforms have been particularly targeted by hackers, though government agencies have not been immune: reports from April 2016 indicate that hacker collective Anonymous breached the Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs' servers and published one terabyte of files online.

Against this backdrop, the Kenyan government is tightening up its cybersecurity policy framework. Privacy International is concerned about the consequences of framing cyber security predominantly as a national security issue and its impact on public understanding of cyber security, opportunities for public debate, transparency, accountability, oversight and human rights. When cyber security becomes primarily the domain of intelligence and law enforcement agencies, public scrutiny of projects and initiatives becomes much more difficult, if even possible.

The National Intelligence Service (NIS) has strategic and operational influence on Kenya’s cybersecurity program. This is particularly concerning given how the NIS operates outside of legal frameworks to surveil individuals, uses pressure to obtain information from private telecommunications operators, and is opaque even to other branches of the security services, as shown in Privacy International’s March 2017 investigation.

Cybersecurity policy in Kenya is set by the National Cybersecurity Steering Committee (NCSC) comprising the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology (Ministry of ICT), the ICT Authority, the Ministry of Interior Coordination & National Government, the NIS, the National Police Service, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), the Communications Authority, the Ministry of Defence and the industry body, the Telecommunications Service Providers of Kenya (TESPOK). Private sector representatives from service providers (Safaricom, Telkom Kenya, Access, and Airtel among others) have also attended meetings. The CA appears to be the organising locus for the NCSC as it usually chairs the meetings, at least in the period 2012 to 2015. The NCSC first met in December 2013.

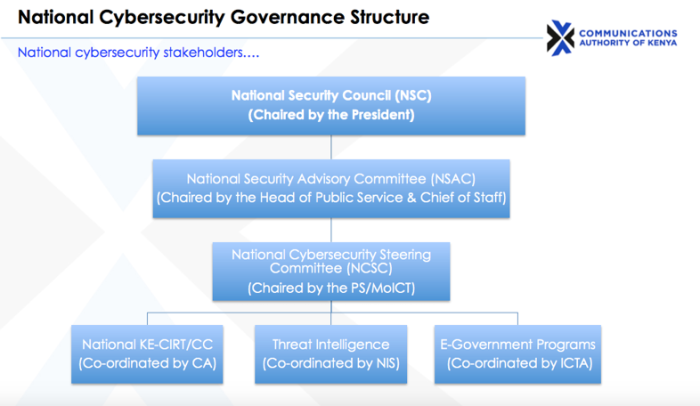

The NCSC itself is subordinate to the National Security Advisory Committee (NSAC), which answers in turn to the National Security Council. Staffed by the President, Vice-President, Attorney General, various Cabinet secretaries and the heads of the NIS, Police, and the Kenya Defence Forces, the National Security Council is mandated to perform supervisory control over the functions of the top security organs in the country. The NIS is thus in charge of the 'threat intelligence' branch of NCSC’s work, as the diagram reproduced below demonstrates.

The NCSC is responsible for managing the Kenya Computer Incident Response Team (KE-CIRT) through a National KE-CIRT Cyber-Security Committee (NKCC). The KE-CIRT is coordinating implementation of the national Cybersecurity Strategy, including the deployment of a national Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). Based at Communications Authority, the KE-CIRT runs a helpdesk to triage the handling process for reported cybersecurity incidents and breaches.

A diagram of cybersecurity bodies in Kenya. From “Overview of Kenya’s Cybersecurity Framework and Related Draft KICA Regulations” presentation by Vincent Ngundi, Communications Authority, 2016.

The NIS also has a major role in the implementation of cybersecurity policies in Kenya, with a strong technical influence. In December 2015, representatives of the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI), Communications Authority, Central Bank of Kenya and Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and members of the multi-agency committee on cybersecurity convened at the NIS to discuss the setting up of a technical committee to oversee cybersecurity implementation in Kenya. This committee would be chaired by NIS, according to correspondence from NIS obtained by Privacy International, and would “make recommendations on how the Cybersecurity unit based at the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) can be improved.”

CA officials have previously stated to Privacy International that no formal relationship with the NIS as regards surveillance exists, but the truth runs somewhat deeper. The NIS’ appetite for communications data and content is avid, and the agency has shown itself willing to operate outside of the legal requirement to obtain interception warrants to conduct surveillance, which has facilitated the commission of grave human rights violations including torture and extrajudicial killings. There is therefore a real concern that Kenya’s cybersecurity infrastructure could also be harnessed to these ends under the banner of cyber security.

The actors involved in Kenya’s expanding cybersecurity framework are discussed below in detail in relation to various projects – the Network Early Warning System (NEWS) and National Intrusion Prevention and Detection System (NIPDS) in particular.

A Grand Plan, With International Help

The National Computer Incident Response Team (KE-CIRT) was created in consultation with International Telecommunications Union; it derives its mandate from the Kenya Information and Communications Act 1998. It has been operational since 2012. The CIRT is responsible for the implementation of the national Cybersecurity Strategy, among other tasks. Among its staff are officers seconded from the police, Kenya Defence Forces and NIS, according to the minutes of the National KE-CIRT Cyber-Security Committee meetings.

Kenya’s cybersecurity initiatives rely heavily on foreign government assistance. The National Cybersecurity Strategy, also referred to as the National Cybersecurity Strategy and Master Plan, was first developed for the Ministry of Information and Communication (MOIC) over four months from July 2012 with a grant from the US Trade and Development Agency for Technical Assistance. Booz Allen Hamilton, a prominent American management firm with significant national security contracts, was contracted to help develop the plan. The resulting National Cybersecurity Strategy was unveiled in May 2014.

In 2012, NCSC members also benefited from trainings facilitated by the US Embassy. One was on the fundamentals of network security while the other was organized by Research in Motion (RIM) on BlackBerry services. The Criminal Investigations Directorate (CID) forensic lab, also, was set up with funding from the US State Department’s Anti-Terrorism Assistance program (ATA) and the German government.

Building The Network Early Warning System

The national security agencies, particularly the NIS, are not limited to making technical recommendations and sitting in oversight boards. The NIS is active operationally, too, which is evident in its involvement in installation of the Network Early Warning System (NEWS).

In February 2012, the Communications Authority, then called the Communications Commission of Kenya (CCK) sent internet service providers letters requesting their help in setting up the NEWS. An accompanying non-disclosure agreement between the CCK and the ISPs characterized the purpose of NEWS as “detect[ing] at the earliest instance, cyber threats targeting Kenya’s Internet infrastructure”. The project would monitor data traffic entering and leaving Kenya through a number of sensors to be installed on these ISPs’ networks, which would then transmit the data to a central node for analysis. The reaction from Kenya’s telecommunications industry was vociferous – the cooperation letters were leaked to the press. Several ISP employees with whom PI spoke generally traced this to ISPs’ concerns about providing an unverifiable level of access to government agencies and potential backlash from clients reliant on their services. The Communications Authority reportedly insisted it would be the sole custodian of the information gathered from the system citing the non-disclosure agreement’s strict confidentiality terms, including use of the data collected.

The NIS has been strongly involved in NEWS’ deployment. In mid-March 2012, NIS agents visited the landing sites in Mombasa of the SEACOM, EASSy and TEAMS submarine cables which carry internet traffic into the country. In a draft letter in which he thanks the Communications Authority for “continued support and the good collaboration with my organization”, the NIS Director General describes further work needing to be done between the NIS’ and the CA’s cybersecurity teams with a Consultant, who is not identified. The NIS was also the only law enforcement agency present at an update meeting in 2014 also attended by TESPOK and the Communications Authority.

Despite industry protestations, by March 2014, the NEWS technology had been acquired and installation was set to begin immediately at ISPs. A preliminary technical survey had carried out at ISPs nationally in 2012. This time the Communications Authority flexed a bit more ‘national security’ muscle to ensure ISP collaboration with the project. It sent a 'secret' letter in early June 2014 to ISPs requesting their help, citing Condition 13.2 of their licensing agreement: “in case the emergency or crisis is related to aspects of national security, the Licensee shall coordinate with the competent entity indicated by the Commission and provide the necessary services in accordance with the instructions of the Commission or the competent entity indicated thereby in accordance with Section 88 of the Act.”

Later that month, on 24 June, the President officially launched KE-CIRT and the National Public Key Infrastructure. Law enforcement and military officers from the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF), Directorate of Criminal Investigation (DCI) and NIS were seconded to KE-CIRT, on consultation with the Ministry of ICT and the President. An NIS officer, Eric Mwangi, was sent off to London to meet with Facebook representatives in late 2014 to seek “online collaboration with social media platforms”, according to September 2014 meeting minutes. Later in 2015, Mwangi, who frequently represents the NIS at the NCSC board, would attempt to order the takedown of a blog critical of the government, according to internal files from surveillance company Hacking Team. The Communications Authority did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Expanding Surveillance With the National Intrusion Prevention and Detection System

In October 2014, the Communications Authority circulated a concept paper for a National Intrusion Detection System (NIDS) – since renamed the National Intrusion Detection and Prevention System (NIPDS). According to its draft project proposal, the new NIDS would “provide a cyber-early warning on any possible attacks on critical Government Internet infrastructure.”

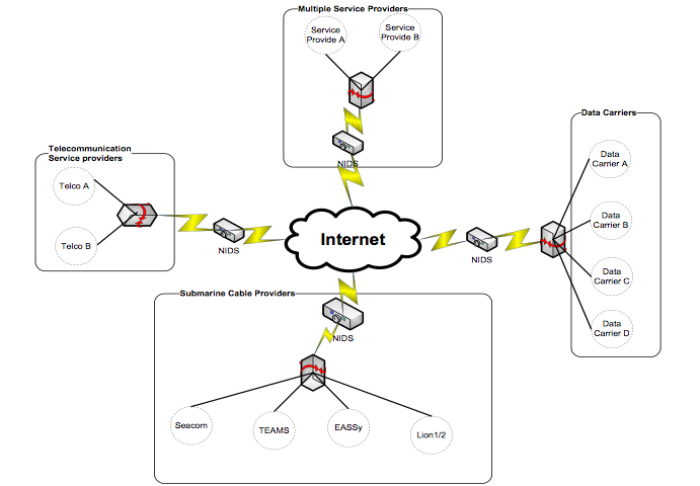

Particularly problematic, however, is the potential scale of monitoring that can be conducted, as well as the lack of transparency about what exactly will be visible and to whom. The NIDS/NIPDS is a monitoring centre housed under the KE-CIRT/CC with “screens with multiple dashboards for recording of various incidents/alerts of possible attack.” NIDS/NIPDS probes would be deployed at the critical nodes of Kenya’s internet backbone: at the Kenya Internet Exchange, at the submarine fibre optic cable landing sites, at the internet service providers and data carriers.

NIDS would be deployed at the ‘critical nodes’ of Kenya’s internet backbone to monitor internet traffic. (“Concept Paper: National Intrusion Detection System (NIDS)”, October 2014). Obtained by Privacy International.

Yet the system is not limited to monitoring broad flows of incoming and outgoing internet traffic in Kenya to detect anomalous patterns. The project appears clearly interested in monitoring content.

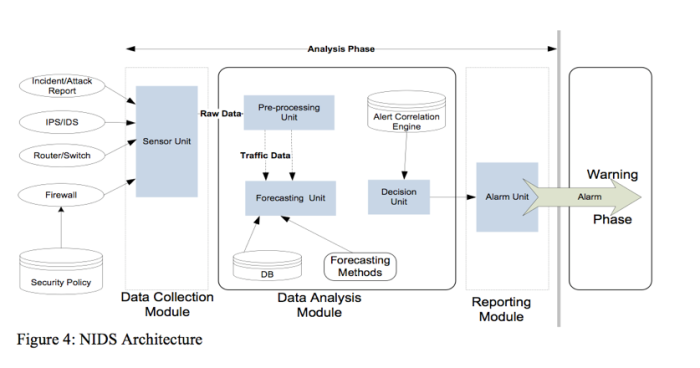

The precise contours of the project are unclear – much of what the probes would be able to collect depends on how they are configured. Certain elements, however, are particularly concerning. As the diagram below demonstrates, sensors collecting ‘raw (internet) data’ would be trained to detect anomalous incidents such as malware, for example, by comparison with a database of known incidents using forecasting methods. The identification of incidents would then result in an alarm being issued. However, given that raw traffic data is being processed, it is unclear what restrictions, if any, would prevent communications or other personal data from being swept up and analysed.

One of the main issues with NIDS/NIPDS is that it is unnecessary to centralise such a system. There are other, theoretically less privacy-invasive methods to ensure Kenya’s cybersecurity – for example, requiring the ISPs, data carriers etc. to install their own cybersecurity intrusion prevention and detection systems at the entry points of their infrastructure that would comply with Communications Authority technical requirements. This would maintain the integrity of the operators’ infrastructure. Instead, what these documents demonstrate, is a plan to deploy a centralised, nationwide infrastructure under the control of the KE-CIRT/CC which is itself run by seconded law enforcement and intelligence officers. This effectively concentrates responsibility for cybersecurity around government agencies, particularly (as noted above) the NIS, which has a demonstrated history of exceeding its legitimate mandate.

NIDS/NIPDS architecture. (“Concept Paper: National Intrusion Detection System (NIDS)”, October 2014). Obtained by Privacy International.

Furthermore, the shortlist of potential suppliers gives a good sense of the government’s thinking on what the NIDS/NIPDS should be able to do, and this is weighted towards surveillance. The list includes several companies well known for surveillance technologies for the massive automated collection of communications data and content: Israeli firms Verint, Septier, and Elta, a division of Israel Aerospace Industries. American firm Palantir, which was also considered for the contract, sells products allowing analysts to crunch large amounts of data to identify individuals and events of interest and their networks. Another proposed American firm FireEye is best known for its tools for malware analysis, but it also sells data centres and platforms and internet monitoring technologies. All of these companies sell technologies which can potentially be used to monitor individuals’ communications and three of the five (with the exception of Palantir and FireEye) are primarily known for the lawful interception technologies they sell.

One component of the NIPDS project, at least, is specifically designed to monitor social media content. Privacy International can confirm that a “media monitoring and management” system was provided by Israeli firm Webintpro following a contract signed in November 2016 with the Communications Authority. Though Privacy International first reported this contract in Privacy International’s March 2017 investigation, according to tender information, the project cost 1.04 billion Kenya shillings (around 7 million USD). Given that this is just one component of the larger NIPDS project, it is likely that the NIPDS is a significant infrastructure project with national scope.

Finally, the Communication Authority’s Director of Information Technology states in the document that procurement of the NIDS/NIPDS would be restricted, i.e. not through a public tender and competitive bidding, as would normally be the case for large-scale civilian infrastructure projects. Instead the project is classed as a “security” project, according to the concept paper. This makes effective scrutiny of the project, its capacities and implications, nearly impossible. The Communications Authority did not reply to repeated requests for comment.

Cyber Security Or Surveillance?

Three documents collectively present Kenya’s cybersecurity vision and strategy. The National Cyber Security Strategy was published in 2014, drafted by the Ministry of ICT. Around the same time, the 2014-2017 National ICT Masterplan was published by a government-assigned taskforce made up of academia, industry and government actors. A draft 2016 National ICT Policy is also currently being circulated, but there is no indication of when it will be approved.

The prominent role of intelligence and law enforcement in Kenya’s cybersecurity initiatives, particularly NEWS, NIPDS and the KE-CIRT strongly suggests the Government of Kenya has steered towards interpreting cyber security as an opportunity for increased surveillance. Good cybersecurity means protecting individuals, protecting devices and protecting networks. Privacy International believes this should form the basis of any cyber security strategy and implementation. Secrecy does not equal security. More transparency is needed around these initiatives, if they are supposed to keep individuals safe.