Data Exploitation and Democratic Societies

Image Source: "Voting Key" by CreditDebitPro is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Democratic society is under threat from a range of players exploiting our data in ways which are often hidden and unaccountable. These actors are manifold: traditional political parties (from the whole political spectrum), organisations or individuals pushing particular political agendas, foreign actors aiming at interfering with national democratic processes, and the industries that provide products that facilitate the actions of the others (from public facing ones, such as social media platforms and internet search engines, to the less publicly known, such as data brokers, ad tech companies and what has been termed the 'influence industry').

Personal data plays a fundamental role in this emerging way of influencing democratic processes. Through the amassing and processing of vast amounts of data, individuals are profiled based on their stated or inferred political views, preferences, and characteristics. These profiles are then used to target individuals with news, disinformation, political messages, and many other forms of content aimed at influencing and potentially manipulating their views.

Data is also becoming integral to the ways in which we vote - from the creation of vast voter registration databases, sometimes including biometric data, to reliance on electronic voting. Such voting processes are often implemented without sufficient consideration for their considerable privacy and security implications.

In attempting to understand and control this increasingly prevalent data exploitation, other actors - including governments, regulators and civil society - are beginning to push for more transparency and accountability regarding how data is used in political processes. While generally positive, this push may have some drawbacks. Many of the efforts so far have focused on regulating content, e.g. demanding the taking down of political or issue-based content, requiring the introduction of fact checking, curbing anonymous posting. Relatively less attention has been paid to measures to prevent the exploitation of personal data to distribute such content in the digital space.

It is therefore more important than ever for us to consider the way in which data is used in the context of modern democratic societies. Left unchecked, such exploitation is highly privacy invasive, raises important security questions, and has the potential to undermine faith in the democratic process, including in relation to transparency, fairness and accountability.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

Data Exploitation and Elections

Nowhere is the increasingly data intensive nature of the electoral cycle more prevalent than in political campaigning. Around the world, political campaigns at all levels have become sophisticated data operations. As the amount of data and the ways it is used increase, so do the risks for data exploitation. This has consequences for the right to privacy and data protection, but also other rights including freedom of expression, association and political participation.

Data driven campaigning has been at the core of recent elections and referenda around the world. Campaigns rely on data to facilitate a number of decisions: where to hold rallies, on which States or constituencies to focus, which campaign messages to promote in each area or to each constituency, and how to target supporters (and people 'like' them), undecided voters, and non-supporters.

Back in 2017, Privacy International looked at the use of data in campaigning in the Kenyan elections, and the role of a US-based digital media company. Since then, the use (and exploitation) of data in campaigning has become ever more acute and pervasive. For example, the use of data for profiling and targeting in political campaigning has come under scrutiny in recent elections in France, Germany and Italy. In the UK, the Information Commissioner's Officer has opened multiple investigations into data use during the Brexit referendum.

Whilst the use of data in political campaigning is not new, the scale and granularity of data, the accessibility and speed of the profiling and targeting which it facilitates, and the potential power to sway or suppress voters through that data is. The actors, tools, and techniques involved - who is using data, where are they getting it, and what are they doing with it - vary depending on the context from country to country and campaign to campaign and even within a campaign. The sources and types of data used in political campaigning are multiple. Political parties and campaigns gain access to data from electoral roll/voter registration records. They also have data on members and supporters, as well as data from canvassing and use of social media, apps, online tracking, surveys, and competitions. Then there is commercial data, that can be tapped into - through data brokers, platforms, and the wider online advertising ecosystem. Tactical Tech has identified over 300 organisations around the world as working with political parties on data-driven campaigning. Data can be exploited through a range of mediums to build profiles and to disseminate messages in a targeted manner, ranging from the use of text messages (SMS), to calls, to messaging apps (e.g. Whatsapp), to search results (e.g. through AdWords), to campaign apps, to ad-supported platforms (e.g. Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram) and websites, to television. A vast range of factors may play a role in the political content you see, including where you've been (e.g. geotargeting - geofencing, beacons), what you've been doing (online and offline) what this says about your personality (e.g. psychometric profiling), and what messages people (like you) with particular traits have been most susceptible too (e.g. A/B testing).

This collection, generation and use of data happens at all times, however, not just during the course of electoral campaigns.

While individuals are targeted as potential voters at key democratic moments, such as political elections and referenda, they are also increasingly targeted outside formal electoral campaigning periods. This targeting may, for example, seek to influence their political views more broadly, or demand they support or oppose a political issue, such as a draft law or a key policy vote in Parliament.

For example, the UAE and Saudi Arabia used online advertising and social media campaigns to seek to influence US policy on Qatar. Exxon Mobile, a US oil company, has spent millions on ads promoting oil production and opposing regulation.

There might not be obvious links between the way the data is used politically, for example in an effort to influence or create division, and a political party manifesto commitment or support or opposition to a referendum.

And political parties are just one of many actors involved. There are many other actors that play a role (whether intentional or unintentional) in political campaigning (including through influencing and nudging), but do not have a direct relationship with or are not affiliated with a particular party or candidate, often raising questions including in relation to finance. For example, during the UK's Brexit referendum, advertisements appeared from apparent 'grassroots' groups, which actually had a large lobbying company behind them.

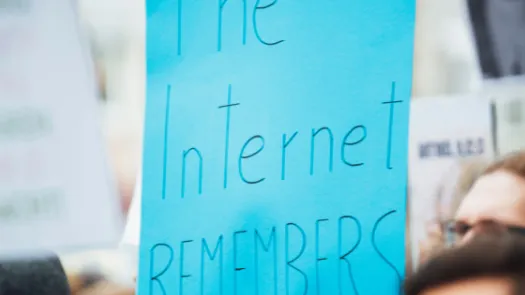

What is clear is that there a serious lack of transparency about who is using this data, where they are getting it and how they are using it. This exacerbates the issues of fairness and accountability. Too often the laws that are meant to protect people's data and regulate the electoral process are not enforced, out of date, or non-existent in the digital data-driven campaign environment, which leads to inherent risks and threats to democracy.

Lack of Transparency

The data exploitation just described is often shrouded in secrecy. Certain actors, including online platforms and social media companies, have begun proposing voluntary ways to increase transparency, particularly with regard to "political advertisements."

At present, people using these platforms are not able to completely understand why they are targeted with any ad, much less a political ad. How ads are targeted at users is incredibly complex and can involve targeting parameters and tools provided by platforms, or data compiled by advertisers and their sources, such as data brokers. What is especially difficult for most users to understand is how data from disparate sources is linked, and how data can be used to profile them in ways that can be incredibly sensitive. These companies' business models necessitate the collection and exploitation of data in ways that are opaque, not only to profile and target people with advertisements, but also to keep their valuable attention on the platform.

Because all advertisements have the potential to be political in nature, steps to increase transparency must be applied broadly and uniformly across advertising platforms and networks, and not limited to ads bought by often self-identified political actors or narrow definitions of "political issues". The steps that certain companies have so far taken to increase transparency are therefore insufficient, including because they often apply only to "political" or "issue" advertisements, as defined by the companies, and reveal too little about how those ads are targeted.

To improve transparency, the European Union developed a code of practice on disinformation aimed at online platforms, leading social networks, advertisers, and advertising industry. It has been signed by Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Mozilla as well as by some national online advertisement trade associations. The code contains a range of commitments mostly focussed on improving transparency of political and issue-based ads, and on limiting techniques such as the malicious use of bots and fake accounts. However, the implementation of this code by the main companies has been patchy.

Companies are also not sufficiently addressing other ways in which data can be exploited to influence elections, including through the promotion of content that is not explicitly identified as an ad.

Data Abuses and Breaches in Electoral Processes

Democratic elections are complex processes that require sophisticated legal and institutional frameworks. Their functioning demands the collection and processing of personal data. Increasingly governments are creating databases which store a vast array of personal information about voters, sometimes including biometric data.

If not properly regulated, these databases may undermine the democratic processes they ostensibly support. For instance, unrestrained sale of the data contained in these databases might exacerbate the profiling concerns articulated above. Insufficiently secure databases might also be subject to breaches or leaks of personal information, which might discourage voters from registering in the first place and could lead to other harms such as identity theft.

For example, in March 2016, the personal information of over 55 million registered Filipino voters were leaked following a breach on the Commission on Elections' (COMELEC's) database. The investigation of the national data protection authority concluded that there was a security breach that provided access to the COMELEC database that contained both personal and sensitive information, and other information such as passport information and tax identification numbers. The report identified the lack of a clear data governance policy, vulnerabilities in the website, and failure to monitor regularly for security breaches as main causes of the breach. Similarly, in 2015, the personal information of over 93 million voters in Mexico, including home addresses, were openly published on the internet after being taken from a poorly secured government database.

As another example, in Kenya during the 2017 presidential election, there were reports that Kenyans received unsolicited texts messages from political candidates asking the receiver to vote for them. These messages referenced individual voter registration information such as constituency and polling station, which had been collected for Kenya's biometric voter register. There are concerns that this database has been shared by Kenya's electoral commission (IEBC) with third parties, without the consent of the individual voters, and that telecoms companies may have shared subscriber information, also without consent, in order to allow this microtargeting to happen. It is not clear who the registration database was shared with and therefore which company, if any, were responsible for this microtargeting. Privacy International's partner, the Centre for Intellectual Property and Technology Law (CPIT) at Strathmore University, Kenya, researched whether the 2017 voter register was shared with third parties, and if so, with whom, finding more questions than answers.

Similarly, increased reliance on technical solutions, such as e-voting, raise the risks of abuse and specific challenges related to the protection of anonymity of voters. For example, in Switzerland researchers found technical flaws in the electronic voting system that could enable outsiders to replace legitimate votes with fraudulent ones.

WHAT IS THE SOLUTION?

Privacy International would like to see stronger enforcement of existing laws and adoption of new regulations to limit the exploitation of data that affects democratic processes. These would need to balance the legitimate interest of political actors to communicate with the public and the right of individuals to be free of unauthorised, opaque targeting.

First, we need a review of existing laws.

Our research suggests that national laws and regulations are often not fit for purpose. There are many laws and regulatory frameworks that are relevant in this space: from electoral law, to political campaign financing, from data protection to audio-visual media rules regarding the broadcasting of political messages.

These laws are often not adequately regulating online data-driven campaign practices. They do not always address the technical and privacy concerns of modern electoral systems that rely on electronic voting and voter databases. And when laws are relevant, they are often not being enforced effectively.

Data protection and electoral laws need to be examined closely in order to address the use of data in electoral campaigns from a comprehensive perspective. For example, data protection law should regulate profiling and not include loopholes that can be exploited in political campaigning. Electoral laws should be reviewed to ensure they apply to digital campaigns in the same way as they might to the print and broadcasting context. There should also be full, timely, detailed transparency of digital campaign financing. Where these frameworks fall short, they should be amended and enhanced.

Second, we need an approach that fosters collaboration and interaction across different actors involved in this field, from election officials, to data protection authorities, from election monitors, to civil society.

As noted recently by European institutions, this is a complex, multifaceted area, with many actors and many interests. It will not be possible for one single regulator, no matter how well resourced, to address all of these aspects.

Third, we need to make sure those actors who can affect change received the support they require, including:

- Empowering regulators to provide clear guidance, take action and enforce the law, having the ability to conduct their work without external pressure and with the ability to request information from all involved parties: political parties, campaign groups, companies, other private actors, and other government actors involved in the electoral cycle. Regulators must be given the necessary resources (financial and capacity) to take such action.

- Capacitating all parties involved in regulating political campaigning, including national electoral commissions and electoral monitoring bodies, on these issues according to their roles, including the type of technologies and methods deployed for campaigning, applicable privacy and electoral law, and on good practices as to how to exercise their powers.

- Supporting civil society and public interest actors seeking to scrutinise, monitor and expose data exploitation in the electoral context.

Fourth, actors who are exploiting data must be held to account:

- Political parties and campaign groups must fully comply with data protection and campaigning/ electoral laws, be accountable for all the campaigning they do both directly and indirectly, and subject that work to close public supervision.

- Companies in the campaigning ecosystem need to be transparent and accountable with regard to the services and products they offer to political parties around the world, and the methods used to obtain and process personal data.

- Companies should also implement best practices across all jurisdictions, not only in those that have legislated or enforced them.

Fifth, companies should expand the scope of their ads transparency efforts to include all advertisements bought on their platforms. Companies should provide users with a straightforward and simple way to understand why they are targeted with an ad, including information such as what the intended audience of the ad was and what the actual audience was. Transparency efforts should be rolled out globally, and must take into consideration regional and local contexts. Such efforts should not be applied in a mechanical or generalist way. Privacy International also believes that there may be a legitimate need to protect political anonymity - such as for civil society working on sensitive issues in certain countries. These nuances must be considered in companies' transparency efforts.

To fully address concerns about targeted advertising, more information should be made easily available to users. Companies should provide information related to microtargeting - if multiple versions of an ad were created, how ad audiences were created, what segments or interests were selected, what data was used by an advertiser to reach the audience or if the audience was generated via a lookalike advertising feature. This sort of information should be understandable to users.

Additionally, it is important for researchers to be able to monitor and study political and issue-based advertising.

Political parties and campaign groups likewise play a role in ads transparency. Political parties should be proactive and take steps to provide transparency to their constituents as to where they are advertising, who they are targeting, and on what topics they are advertising.

Finally, companies should comply with and support strong regulation to protect privacy. Companies may need to make significant changes in the ways in which they permit targeting of individuals with political ads, with many such practices likely to fall short of modern data protection laws, such as the EU's General Data Protection Regulation. While increased transparency is welcome, it cannot stop there.

WHAT PI IS DOING

In 2017, PI revealed how two highly problematic and inflammatory political campaigns were created by a US-based data analytics company on behalf of Kenyan President Kenyatta’s re-election campaign. Our investigation, which was released prior to the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal, showed how data companies are able and willing to insert themselves into national politics around the world.

Also in 2017, PI challenged an exemption in the UK's new data protection regime which may be used to facilitate data exploitation. We wrote to the UK's main political parties seeking assurances that they would not rely on this loophole.

In 2018, PI investigated seven data analytics and data broker companies to understand how the companies profile people and where the companies get the data to do so. A number of these companies have been linked to political parties and campaigns. Our investigation showed how it is currently impossible to understand the sources and use of such data, and resulted in PI filing regulatory complaints against all companies. We are in ongoing conversations with the relevant regulators regarding those complaints.

Also in 2018, the Guardian newspaper revealed that Cambridge Analytica - company purporting to facilitate digital campaigning - was able to harvest data from Facebook. By Facebook's own design, companies like Cambridge Analytica were able to amass data on users' friends. In the case of Cambridge Analytica, they were able to amass data on 87 million people, the vast majority of whom had never interacted with Cambridge Analytica in the first place. PI was quick to develop policy objectives, key questions for Facebook to answer, and to engage our global network of partner organisations to respond. We worked closely with media organisations to ensure that this story received sufficient attention.

In 2019, PI is:

- Taking stock and learning from our own past experience and that of others (for example, experiences in France, Italy and Germany)

- Continuing to pressure actors within the adveristing space, including ad tech companies and data brokers (for example, we continue to pursue these complaints)

- Working with partners (for example, earlier this year we joined with Mozilla and other civil society organisations to write to Facebook)

- Reviewing legal frameworks and identifying: what works, what doesn't, what needs enforcement, what needs to be strengthened (for example, assessing the effectiveness of the measures taken by the EU around the European Parliament elections in May 2019)

- Developing policy recommendations and advocating for their adoption (for example, engaging with election monitor organisations to support their assessment of the data protection aspects of the national electoral legal frameworks)

- Demanding relevant actors - government and corporate - comply with their commitments and the law

- Fighting for people to be able to understand when they are being shown an ad and why

- Challenging data monopolies