When Local Authorities aren't your Friends

UK Local Authorities are looking at people’s social media accounts as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation tactics.

- A significant number of local authorities are now using 'overt' social media monitoring as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation activities. This substantially out-paces the use of 'covert' social media monitoring

- If you don't have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

- There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making.

- Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

It is common for families with no recourse to public funds who attempt to access support from local authorities to have their social media monitored as part of a ‘Child in Need’ assessment.

This practice appears to be part of a proactive strategy on the part of local authorities to discredit vulnerable families in order to refuse support. In our experience, information on social media accounts is often wildly misinterpreted by local authorities who make serious and unfounded allegations against our clients.

In some cases, local authorities will go so far as to use such information to make accusations of fraud and withhold urgently needed support from families who are living in extreme poverty.

This practice often leaves families too afraid to pursue their request for support, which puts them at greater risk of destitution, exploitation, and abuse.

Eve Dickson, Project 17

SUMMARY

Since 2011, the UK Chief Surveillance Commissioner, the regulator responsible for oversight of surveillance powers used by local authorities, has raised concerns about local authorities using the internet as a surveillance tool. By 2017, such was the concern that Lord Judge wrote to every local authority suggesting that they conduct an internal audit of the use of social media sites and the internet for investigative purposes.

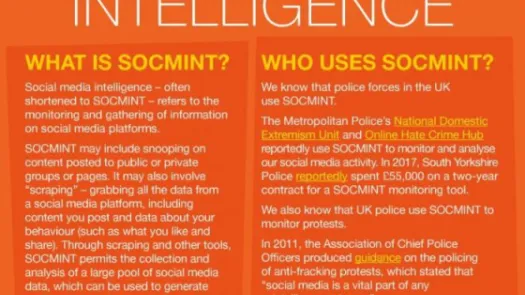

Social media platforms are a vast trove of information about individuals, including their personal preferences, political and religious views, physical and mental health and the identity of their friends and families. Social media monitoring refers to the techniques and technologies that allow the monitoring and gathering of information on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

The Surveillance Commissioner’s Guidance defines overt social media monitoring as looking at ‘open source’ data, being publicly available data and data where privacy settings are available but not applied. This may include:

- List of other uses with whom an indiviudal shares a connection (friends/followers);

- Users’s public posts: audio, images, video content, messages

- Likes, shared posts and events

“Repetitive examination/monitoring of public posts as part of an investigation” constitutes instead ‘covert’ monitoring and “must be subject to assessment and may be classed as Directed Surveillance as defined by RIPA.”

What PI found out

In October 2019 Privacy International sent a Freedom of Information request to every Local Authority in Great Britain asking not only about whether they had conducted an audit, but sought to uncover the extent to which ‘overt’ social media monitoring in particular was being used and for what Local Authority functions.

We have analysed 136 responses to our Freedom of Information requests, being those that had been received by November 2019. All responses are publicly available on the platform What Do They Know. In this report we include excerpts from the responses we received to better illustrate the use of these practices.

Our investigation has found that:

- A significant number of local authorities are now using ‘overt’ social media monitoring as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation activities. This substantially out-paces the use of ‘covert’ social media monitoring

- If you don’t have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

- There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making.

- Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

1. A significant number of local authorities are now using ‘overt’ social media monitoring and this substantially out-paces the use of ‘covert’ social media monitoring

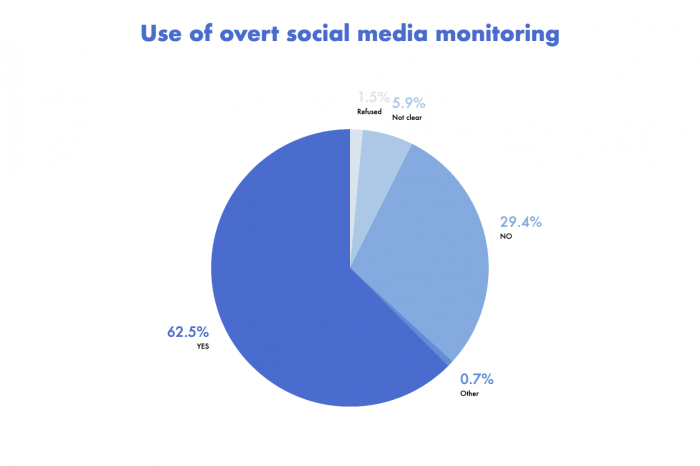

We reviewed responses to our FOIA request from 136 Local Authorities and found out that:

- 62.5% of Local Authorities are using ‘overt’ social media monitoring

- 31% of Local Authorities are using ‘covert’ social media monitoring

- 23.1% of Local Authorities who aren’t using ‘overt’ social media monitoring still have a policy/guidance on carrying out this type of surveillance

“The use of the internet as an investigative method is now becoming routine.”

London Borough of Ealing RIPA Policy and Guidance

Colchester’s ‘Use of Social Media in Investigations Policy and Procedure 2018/19’ says:

Social Media has become a significant part of many people’s lives. By its very nature, Social Media accumulates a sizable amount of information about a person’s life, from daily routines to specific events. Their accessibility on mobile devices can also mean that a person’s precise location at a given time may also be recorded whenever they interact with a form of Social Media on their devices. All of this means that incredibly detailed information can be obtained about a person and their activities.

Social Media can therefore be a very useful tool when investigating alleged offences with a view to bringing a prosecution in the courts. The use of information gathered from the various different forms of Social Media available can go some way to proving or disproving such things as whether a statement made by a defendant, or an allegation made by a complainant, is truthful or not. However, there is a danger that the use of Social Media can be abused, which would have an adverse effect, damaging potential prosecutions and eve leave the Council open to complaints or criminal charges itself.

2. If you don’t have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

The respect given to an individual’s privacy by local authorities, in relation to what individuals say and do online, appears to be based on the arbitrary distinction of privacy settings.

If you have applied access controls then you have a ‘reasonable expectation of privacy’ in relation to your social media posts. But if you do not apply privacy settings the data may be considered open source and overt social media monitoring can take place without any authorisation.

This distinction is supported by the Home Office guidance and guidance from the Regulator (Investigatory Powers Commissioner).

Where privacy settings are available but not applied the data may be considered open source and an authorisation is not usually required. The fact that an individual is not told about “surveillance” does not make it covert. Notice the words in the definition of covert; “unaware that it is or maybe taking place.” If an Officer decides to browse a suspect’s public blog, website or “open” Facebook page, this will not be regarded as covert.”

Blaenau Gwent Country Borough Council Guidance

This arbitrary distinction is flawed and unsophisticated. If you don’t know how to check your privacy settings or use social media platforms that have no settings, your information is likely to be treated as ‘open source’ and local authorities can look at it for ‘intelligence gathering’ and ‘investigations’ without you ever knowing.

Cheshire West and Cheshire state that:

“Some users will not set any privacy settings at all meaning that the information they post is publicly available. Individuals that operate with no, or limited, privacy settings do so at their own risk…

This puts the onus on individuals to understand and check their privacy settings, and fails to recognise that:

- Privacy settings vary from platform to platform and also change constantly over time in a way that requires constant vigilance of users to maintain a privacy status quo.

- People share vastly more personal information about themselves, their friends and their networks than they would if a local authority requested this type of information.

- Control of what data about you is made public on social media is not simply a matter of easy voluntary choice. For example, in 2018 a Facebook bug changed 14 million people’s privacy settings.

As noted by authors Lilian Edwards and Lachlan Urquhart, privacy settings constantly change and can apply differently to different content. In addition, social media sites are motivated by making user content as public as possible and thus difficult for an individual to protect. individuals may share without necessarily being aware who can access their information and how it is used. We further note they may differ depending on other factors such as jurisdiction and device used.

… contrary to popular belief, control of what data about you is public on social media is not simply a matter of easy voluntary choice. Accordingly, the common retort – if you didn’t want people to read it, why did you make it public? – is not in fact a sensible question to ask. We would argue this contributes strongly to an argument that material placed on “open” social media can still carry with it reasonable expectations of privacy.

…privacy settings vary from platform to platform and also change constantly over time in a way that requires constant vigilance of users to maintain a privacy status quo. Different privacy settings, and different changes, apply to different types of content e.g. posts, comments, groups, photos, friends list etc. On most sites, as with Facebook, the overwhelming motivation is to make as much material as possible public to maximise growth of audience and collection of data for marketing revenue. Hence it is well known that many are deluded in their belief that they have adequately protected their privacy via code controls. Indeed Madejski, Johnson and Bellovin found that in a small study of 65 university students, every one had incorrectly managed some of their Facebook privacy settings, thus displaying some personal data to unwanted eyes.

Lilian Edwards and Lachlan Urquhart, ‘Privacy in Public Spaces: What Expectations of Privacy do we have in Social Media Intelligence'

Repeated viewing

In addition to the relevance of privacy settings, when social media monitoring of ‘open source’ data involves repeated viewing of an individual’s social media, authorisation is required and the regulator’s guidance, which has influenced local authority guidance, states that it should be treated as ‘covert’ rather than ‘overt’ social media monitoring.

Casual (one-off) examination of public posts on social networks as part of investigations undertaken is allowable with no additional RIPA consideration. Repetitive examination/monitoring of public posts as part of an investigation must be subject to assessment and may be classed as Directed Surveillance as defined by RIPA.

Arun District Council Guidance on the Use of Social Media in Investigations

Yet there is a lack of constitency as to what constitutes repeat viewing, thus ‘covert’ and what is ‘overt’. Can ‘overt’ include:

- Downloading audio and video or taking screenshots of text, status updates and photographs (Cheshire West and Chester);

- Spending three weeks googling or otherwise monitoring a person’s name (Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council)

- Visiting a social media platform twice (rather than one-off) (Lincoln City Council)

3. There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making

We asked local authorities if they were able to state how regularly social media monitoring is used and if so to provide figures. We reviewed responses to our FOIA request from 136 local authorities and examined the responses of those local authorities who stated that they use overt social media monitoring:

- The majority of local authorities who conduct ‘overt’ social media monitoring do not monitor i.e. audit this use of ‘overt’ social media monitoring.

- In most cases of ‘overt’ social media monitoring, there is rarely any form of authorisation and there is an absense of accountability.

- There is no guidance or requirement from the Investigatory Powers Commissioner (the regulator) to the local authorities requiring them to track and audit the use of overt social media monitoring.

- 60% of local authorities who use ‘overt’ social media monitoring do not provide training for staff.

The responses to the question which sought to find out whether local authorities were reviewing the use of over social media monitoring were confusing, whcih makes it difficult to draw out any clear satistics from the replies.

‘Overt’ social media monitoring appears to be used on an ad hoc basis, and even in the few cases where there many be initial authorisation, there is an absence of assessment about whether the use was effective. This means that local authorities are using this surveillance tool without any proper way to assess whether it improves rather than undermines the quality of decision making.

Accountability and legitimacy

Decision making by local authorities can have serious consequences for individuals.

Yet local authorities are not able to reliably state whether overt social media monitoring, based on the arbitrary distrinction of an individuals’ privacy settings, is effective in investigations and intelligence gathering. They cannot assess how correct they are on deciding integrity of motive of an individual based on social media output; they cannot judge whether they are adept in relation to new forms of online behaviour, norms and languages.

There has been an absence of public and parliamentary debate on this tactic and fundamental issues such as the legitimate aim of such activities and whether it is necessary and proportionate. This must take place as a matter of urgency given that a number of local authorities have indicated an expansion of their use of overt social media monitoring.

In addition, overt social media monitoring should not continue unless local authorities, supported by the Investigatory Powers Commission, have processes and procedures to first seek internal authorisation to conduct overt social media monitoring (notably a few currently do); and secondly to be able to monitor effectively and centrally audit (at the local level) the use of overt social media monitoring.

We are concerned that not enough consideration has been given to the inherent lack of data integrity, authenticity, veracity or the social context of conversations that may take place on social media. Leading to potential misinterpretation and reliance upon misleading ‘evidence’.

These risks may become more pronounced if and when local authorities move to using social media analytics tools in their investigations, rather than manual checks on an individual’s Facebook posts.

4. Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

We found that Local Authorities are using ‘overt’ social media monitoring in the following areas:

- Recovery of unpaid Council Tax arrears

- Debt recovery

- Regulatory Services/Trading standards e.g. allegation of advertising illegal goods

- Neighbourhood Services

- Licensing

- Corporate Anti-Fraud teams / Revenues and benefits

- Environmental investigations

- Children’s social care

- Monitoring protests and demonstrations

The various use cases outlined above should be seen as part of a broader apparatus being deployed, where social media monitoring plays a role. Privacy International’s work ‘When Big Brother Pays Your Benefits ’ examines the use of technology as a magic cure-all to socio-economic and political issues.

Newly established or reformed social protection programmes have gradually become founded and reliant on the collection and processing of vast amounts of personal data and increasingly the models for decision-making include data exploitation and components of automated decision-making and profiling.

While social media monitoring by local authorities in Great Britain, at present, involves a manual check of individuals social media such as their Facebook page, as the use of such monitoring increases and is used in a wide variety of areas in which local authorities are active, so too will the prospect of automating such checks and monitoring. In turn, such practices lead invariably to automated decision-making, profiling and the inherent risks of such practices. This will be at the cost of individuals privacy, dignity and autonomy.

Therefore, is it vital that the collection and processing of personal data obtained from social media as part of local authority investigations and intelligence gathering, are strictly necessary and proportionate to make a fair assessment of an individual. There neds to be effective oversight of use of social media monitoring both overt and covert to ensure that particular groups of people are not disproportionately affected, and where violations of guidance and policies do occur, they are effectively investigated and sanctioned.

We further note that for example Oldham Council uses social media monitoring in relation to protests and demonstrations and to identify a groups’ activities. The unregulated use of social media monitoring negatively affects the right of freedom of peaceful assembly. It has a chilling effect on individuals wishing to organise online, as well as using social media platforms to organise and promote peaceful assemblies.

Conclusion

We live in an age where our communications and interactions with individuals, friends, organisations, governments and political groups take place on social media. It has provided an opportunity for the instantaneous transfer and publication of our identities, views, interactions, and emotions. The growing intrusion by government authorities’ risks impacting what people say online , leading to self-censorship, with the potential deleterious effect on free speech, and other fundamental rights.

We have seen the way it is already being used to monitor recipients of welfare benefits, as part of immigration enforcement mechanisms as well as to crack down on civil society.

We may have nothing to hide, but if we know our local authority is looking at our Facebook, we are likely to self-censor. The impact is a reframing of social media platforms, users and data in terms of intelligence gathering and criminality.

Whilst we may be living much of our lives onto social media sites, we provide information, however innocuous, that we are unlikely to share with local authorities when asked directly, unless we are given proper reason and opportunity to object.

As Local Authorities seize on the opportunity to use this treasure trove of information about individuals, their use of social media is set to rise and in the future we are likely to see more sophisticated tools used to analyse this data, automate decision-making, generate profiles and assumptions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Investigatory Powers Commissioner:

- The IPCO should call for guidance setting out guidelines, with concrete examples, by which local authorities may assess:

- What constitutes a legitimate aim for local authorities to rely on in order to conduct overt social media monitoring

- In what circumstances overt social media monitoring is just and proportionate to these legitimate aims

- Whether repeated or persistent viewing constitutes directed surveillance

To the local authorities:

- Local Authorities should refrain from using social media monitoring, and should avoid it entirely where they do not have a clear, publicly accessible policy regulating this activity

Where exceptionally used:

-

Local authorities should use social media monitoring only if and when in compliance with their legal obligations, including data protection and human rights.

-

Every time a local authority employee views a social media platform, this should be recorded in an internal log including, but not limited to, the following information:

- Date/time of viewing, including duration of viewing of a single page

- Reason/justification for viewing and/or relevance to internal investigation

- Information obtained from social platform

- Why it was considered that the viewing was necessary

- Pages saved and where saved to

-

Local authorities should develop internal policies creating audit mechanisms, including:

- The availability of a designated staff member to address queries regarding the prospective use of social media monitoring, as well as her/his contact details;

- A designated officer to review the internal log at regular intervals, with the power to issue internal recommendations