Country case-study: sexual and reproductive rights in Argentina

This country case-study was informed by research carried out by Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia Y Género (ELA)

- There are legal, judicial and administrative barriers that create unwarranted obstacles and delays in the access to legal abortion services, that especially affect poor, rural, indigenous women, girls and adolescents, and those with disabilities

- There is a significant presence of foreign anti-reproductive rights organisations in Argentina and their funding of local organisations is expected to be much bigger.

- There are information, geographical, institutional, and economic barriers that constrain people's access to modern contraception

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

4. What are the concerns regarding the use of technology by anti-reproductive rights organisations?

5. What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence?

This research was commissioned as part of Privacy International’s global research into data exploitative technologies used to curtail women’s access to reproductive rights.

Read about Privacy International’s Reproductive Rights and Privacy Project here and our research findings here.

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

Even though abortion is legal in certain cases in Argentina, different types of barriers restrict the access to legal abortions, contribute to insecure practices and impose a stigma on the women that need an abortion and on the health professionals that seek to guarantee the practice[1]. These barriers interact and deepen even more the difficulties experienced in the access to legal abortion services[2].

Legal barriers

Since 1921, article 86 of the Argentine Criminal Code establishes 3 exceptions to the criminalisation of abortion: 1) danger to life; 2) danger to health; 3) pregnancy resulting from sexual violence. However, there is a gap between the regulatory framework and the effective implementation of these rights.

In order to end the prosecution, hindering and/or delaying of the access to legal abortions, in 2012 the Supreme Court of Justice of Argentina issued the ruling “F., A.L.”[3]. In this ruling the court recognized non-punishable abortion as a women's right; defined that the legal indication on rape extends to any woman, adolescent or girl; argued that a sworn statement in the health service is sufficient for the access to abortion for rape (and a police report is not required); considered that the “judicial permission” to obtain a non-punishable abortion is unnecessary; and provided that the State, both national and provincial, should adopt measures to guarantee access to legal abortion[4].

Despite the legal framework in place and the historic F., A.L. ruling, neglect and violations still persist and block the access to these reproductive health services. One of the main barriers continues to be the inconsistent implementation of the country’s legal abortion framework at the provincial level[5]. As Argentina is a federal country and the health services are regulated per province, the access to legal abortion remains very unequal between provinces. In 2019, progress has been made with the first legal abortion protocol with a ministerial resolution[6] to which nine jurisdictions already adhered[7]. However, six jurisdictions still do not have protocols in place to guarantee the access to these services[8].

On the other hand, excessive prosecution of health practices continue being a main barrier that delays and hinders the access to legal abortion[9]. This is a strategy that is promoted by opposition groups, who also take legal actions against women, health professionals and the Argentine State. Almost every positive development with regard to abortion regulation is met with legal actions by groups opposed to reproductive rights, for example their legal actions against the previous mentioned abortion protocol of 2019[10]. Although these actions are often unsuccessful, they do delay the positive developments and impede the access to these services. The criminalisation and prosecution of abortion negatively impacts the access to legal abortions. as it prevents women from going to health care services and exposes them to illegal and, in some cases, unsafe practices[11].

These legal, judicial and administrative barriers create unwarranted obstacles and delays in the access to legal abortion services, that especially affect poor, rural, indigenous women, girls and adolescents, and those with disabilities[12].

Economic barriers

In Argentina, there should be universal and free access to legal abortions as it is a legal health practice, however, due to the stigma, lack of knowledge and the institutional barriers in place, in practice it is not a universally accessible health procedure. This situation disproportionately affects the poorest women, adolescents and girls, since those with more resources will be able to access to safe abortion care in private clinics[13].

The inclusion of abortions in the Compulsory Medical Plan (PMO, for its acronym in Spanish) is a legal request that has been made by civil society organisations for years. As the current government is preparing a bill to legalise abortion (the Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy bill), there are expectations that they will include this claim[14]. This is seen as a means to naturalise the practice and remove its stigma.

Information barriers

Accessibility to abortion requires the production of information on abortion services at all levels[15]. Due to its federal composition, in Argentina it is the federal state and the provincial states that participate in the production of official information on the health system through different registry systems. However, the official registry system does not account all the legal abortions that are provided in the country, these omissions and deficiencies in the registry system impact the quality of the health policies as there is little information on the existing abortion demands and needs. The inequalities and injustices that characterize the access to legal abortion at the subnational level and at the different health systems of the country are made invisible through these registration failures[16].

On the other hand, information barriers also influence the information given to women in sexual and reproductive health counselling and in the areas of information provision and sex education. In these cases, the lack of guarantees on the provision of complete information is reinforced with the intentional concealment of information or the provision of false information, as is done by opposition-minded health professionals or organisations.

Geographical barriers

The obligation to provide legal abortion services implies the guarantee of availability and accessibility throughout the country, with special care to the most geographically marginalized populations[17]. However, as already shown in the previous sections, abortion services are very unequally distributed and available throughout the country. Due to Argentina’s federal composition, its decentralisation of health services and the uneven political commitment of the provincial governments, especially women in poor, rural and conservative areas face severe barriers in their access to abortion. On the one hand, there are less facilities that provide legal abortions, and on the other hand, the opposition groups and opposition actors often have a larger presence and more influence in the politics and society of these areas through which they impede the practice and its access[18].

Social barriers

In Argentina, religious actors and institutions continue to have a large influence in the local, provincial and national governments. And also in society, religion remains very present: in a recent study 66% of the survey respondents defined themselves as Catholics[19]. This religious presence influences how abortion is treated socially. Although the parliamentary abortion debate in 2018 triggered the social decriminalization of abortion[20], where the subject was openly discussed in politics, TV shows and families, there still exists a strong stigma and related social pressures. This social abortion stigma is the main social barrier women face when seeking interruption of pregnancy[21], it defines where and when women accede to abortion attention and care[22].

Institutional barriers

Conscientious objection is frequently practised in Argentine health institutions and sometimes even occurs across the entire department or establishment, resulting in one of the main institutional barriers to legal abortion services[23]. It also contributes to the abortion stigma and fuels the idea that abortion is illegal[24]. Professionals who work in hostile environments and provide abortions do not speak openly about their work. This silence is part of the stigma and perpetuates the stereotype that abortion is something deviant or unusual[25].

Another institutional barrier is the restricted access to abortion medications. In Argentina, the production and marketing of mifepristone is not authorized and there is restricted access to misoprostol. After several requests from civil society and health professionals, in 2018 the National Institution for the Administration of Medicines, Food and Medical Technology (ANMAT, for its acronym in Spanish) authorized the production and marketing of misoprostol for obstetric and gynaecological use, and enabled the sale in Pharmacies under medical prescription, in addition to Health institutions[26].

However, in 2019 opposition groups impeded the sale of misoprostol in pharmacies through legal actions. Asociación para la Promoción de Derechos Civiles (“Association for the Promotion of Civil Rights”) and Civil Association Portal de Belén requested a precautionary measure before the Federal Administrative Court No. 11. This court partially upheld their request, as they suspended the sale of misoprostol in pharmacies, however, the associations’ request to nullify the 2015 abortion protocol was rejected[27].

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

In 2019, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) published a report that states that 66% of Argentine women between the ages of 15 and 48 use modern contraception[28]. In Argentina, access to contraception methods is regulated by law No. 25,673 (2002) on sexual health and responsible procreation. This law and law No. 26,130, on surgical contraception, establish free access in public and private hospitals and health centres, to the following contraception methods included in the Mandatory Medical Programme (PMO, for its acronym in Spanish): condoms, pills, injectables, IUDs, emergency contraception and surgical contraception (tubal ligation and vasectomy)[29].

The National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation, created as a result of Law No. 25,673, is responsible for the implementation and construction of public policies on sexual and reproductive health. Its objectives are the promotion and guarantee of information, guidance, methods and services. The Program promotes the provision of high quality information by all health institutions and also provides contraception methods to the provinces to be distributed in health centres free of charge and with appropriate advice[30].

Argentina thus has a strong set of norms and public policies to guarantee the access to modern contraception methods. However, barriers to the access to modern contraception still exist and they are mainly related to barriers enforced by anti-reproductive rights actors and the challenges imposed by Argentina’s federal composition and health system.

Legal barriers

A barrier in the implementation of the regulatory framework on sexual and reproductive health has been the legal actions from opposition groups. Since their creation, the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation and the National Ministry of Health have faced multiple legal actions against the free distribution of hormonal and emergency contraception and other services, brought by various actors and before different (provincial) courts[31].

An example of such legal actions is the action of protection presented by the civil association Mujeres por la Vida (“Women for Life”) in 2008, accompanied by Portal de Belén, against the Province of Córdoba, to prohibit the provision of the morning-after pill as a contraceptive method[32]. After more than a decade, the ruling is still pending. In 2011, Mujeres por la Vida also filed an action of protection against the National Ministry of Health, arguing that the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation was unconstitutional, as it supposedly nullified the constitutional rights of parents, with respect to their children’s education and provision of family planning services[33]. The claims were rejected in two instances. More recently, the inclusion of hormonal treatments for trans people was also met with an action of protection by Partido Demócrata Cristiano (“Christian Democratic Party”) and the anti-rights lawyer Ernesto Lamuedra, against the National Ministry of Health, arguing that it is unconstitutional and it injures, alters and threatens the rights and guarantees of children[34].

Although not always successful, these legal actions interfere with the access and availability of the reproductive services.

Information barriers

One of the main barriers to the access to contraception methods is the lack of knowledge about the right to and the existence of these services[35]. Although provincial and national governments actively inform on sexual and reproductive services, information barriers continue to influence the information that women receive. Anti-reproductive rights actors actively generate stigma, conceal information or provide false information.

Comprehensive sex education is crucial for the reduction of these information barriers. In 2006, the Comprehensive Sexual Education Law No. 26,150 was approved, which universalises the obligation of this education in all public and private educational institutions[36]. This law created the National Comprehensive Sexual Education Program with, among others, the objective to ensure the transmission of relevant, accurate, reliable and up to date information on the different aspects involved in comprehensive sexual education[37]. It also established that the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology would define Curricular Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexual Education and disseminate it to all of its jurisdictions. Between 2009 and 2010, educational materials with a gender perspective were developed and distributed to all jurisdictions, but also nowadays this distribution of information continues through provincial actions and face-to-face training of teachers[38].

However, its effective implementation remains a problem. According to information from the Ministry of National Education, 75% of the adolescents in the last two years of high school indicate that the school does not offer them topics that are of interest to them, such as the contents of comprehensive sex education[39]. In Argentina there is public and private education. The private education often responds to some belief system (there are private Catholic, Jewish, and Evangelical schools) and even though the obligations imposed by the Ministry of Education also apply in these cases, they adapt their sex education classes to their own interests. The Federation of Religious Educational Associations of Argentina (FAERA) for example has stated that the State must be “highly respectful” of the different convictions and educational institutional ideologies, without imposing “ideologies”[40].

In the legislative abortion debate in 2018, both pro-reproductive rights and opposition actors and politicians argued for the importance of a better implementation of this education and it looked like a consensus was reached. Shortly after some progress was made: in 2018 a Resolution by the Federal Education Council, No. 340/18, was issues with the objective of effectively enforcing the Law. However, after the defeat of the abortion bill and with the resurgence of the anti-reproductive rights movements, a strong movement surged against comprehensive sexual education[41]. The most prominent actor behind this is the “con mis hijos no te metas” (“do not mess with my children”) campaign. There are several organisations associated[42] with this campaign that persuades teachers from giving comprehensive sex education throughout the country, with official Facebook pages for the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and all of the provinces[43].

Geographical barriers

The creation of the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation in 2003 represented an important boost to the removal of geographical barriers to the sexual and reproductive health services. The Program purchases the necessary supplies, among other things the contraception methods, which then are distributed to the provincial programs[44]. Given that the provinces are directly responsible for health management, the implementation of the program made it possible to increase the free availability of contraception supplies throughout the national territory and to coordinate and support provincial initiatives[45]. There are sexual and reproductive health counselling services in health centres and hospitals, specially designed so that trained staff can give personalized advice to women, girls and adolescents. These counselling services, among other things, seek to increase and improve the access to information, contraceptive methods, and health care services[46]. Although this distribution system has improved the access to contraception methods and the services are more widely available, there are still geographical barriers for poor women, girls and adolescents who live in rural and isolated areas and have to travel to be able to make use of these services.

Institutional barriers

As indicated in the previous sections, the availability of sexual and reproductive health services has improved greatly with the implementation of the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation. However, the persistent and arbitrary use of conscientious objection regarding sexual and reproductive health has constituted a significant barrier to these services in health institutions[47]. The law underpinning the creation of the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation allows “confessional institutions” to not prescribe or supply the common and widespread contraception methods. In many hospitals and primary care centres, professionals deny abortion care because of personal beliefs, religious beliefs, professional ignorance and/or prejudices, but they do not pre-emptively define and classify themselves as “objectors of conscience”, so women, girls and adolescents are not aware until their first consult at these services or with these professionals[48].

Economic barriers

The draft budget for the 2019 financial year showed an increase of 69% of the budget assigned to the National Program for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation[49], however it is feared that there was a significant under-execution of the budget as research shows that in June 2019 only 13.7% of the budget had been executed[50]. The true execution of these items is still being monitored by civil society and feminist organisations.

On the other hand, although modern contraception is included in the Mandatory Medical Programme (PMO, for its acronym in Spanish) and should enjoy free access, economical barriers still persist. There are strong indications that its coverage is insufficient: almost 13 years after the National Program was implemented, only half or a little more of the women who use these methods or services receive them for free[51]. In the public services, the proportion of free use also varies between the different types of methods[52]. Many health insurance companies or prepaid private health systems deny the free use to their users, arguing that the plan does not contemplate it, or directly not informing them about this right[53].

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

In Argentina, there are several official programs whose main objectives revolve around offering correct and scientific based information in order to promote prevention (whether it is about unwanted pregnancies, STDs, contraception, and also about gender based violence, equality, stereotypes and sexual identity). Since 2006, Argentina has had the Comprehensive Sexual Education Law (Law No. 26,150)[54], the main objective of which is to guarantee comprehensive sexual education (ESI, for its acronym in Spanish) for all children and adolescents. On the other hand, since 2017 the Pan ENIA[55] (for its acronym in Spanish, which translates to “National Plan for the Prevention of Unintentional Pregnancy in Adolescence”) has been activated, this Plan involves the execution of different campaigns and dissemination of information through their website and social networks in order to prevent unintended pregnancies. Both programs have school age minors as their main audience.

For the implementation of these programs, special teams were formed (made up by members of the national ministries of Health and of Education as well as experts on the subject) who were in charge of preparing the materials. Despite the existence of both programs, multiple barriers can be identified, ranging from the lack of interest of some schools in using these contents (there are secular schools that refuse to offer sex education) to conflicts with the provincial ministries for imposing these classes.

According to a report[56] published in March 2020 by UNFPA “in 2017, 704,609 boys and girls were born, of which 13% (94,079) were sons or daughters of adolescents under 20 years old and 2,493 of girls under the age of 15”. Pregnancy in adolescence generates costs for the Argentine State of approximately $32 billion pesos per year.

During the legislative debate on the legalisation of abortion, comprehensive sex education became a fundamental point of discussion. Those who were against the law argued that the state should guarantee prevention and education to society (starting with adolescents) in order to eliminate the abortion needs. They were also promoting a change in the legislation and the content of the ESI in order to remove the misnamed “gender ideology” and obtain more conservative and biologic content. They also intended to remove the abortion information. In this way, the classes the children and adolescents would receive would be based only on prevention of STDs in heterosexual relationships. During these debates, these groups tried to cast doubts[57] on the effectiveness of birth control methods and also the unspoken longterm consequences (they imposed the idea that the birth control pill or the day after pill could cause cancer).

Also during the debate, some members of these groups presented their ideas before the legislators. One of them was Dr. Abel Albino who argued that “the prophylactic does not offer protection from anything, because the AIDS virus goes through porcelain”[58]. After this declaration, the statement of Albino was rejected by medical organisations and NGOs dedicated to health. The then Minister of Health, Adolfo Rubinstein, repudiated the declarations by Albino and explained on different media outlets that Albino’s declarations “are very dangerous because they can lead people to believe that condoms are not an effective method”[59].

Different campaigns to provide the correct information started in order to control damage over what Albino said. On one hand, different NGOs such as Fundación Huesped (an NGO that works with HIV)[60], Fundación FEIM (an NGO for women's rights), Casa Fusa (an NGO for sexual and reproductive health care) and Amnesty International Argentina repudiated the declarations and issued statements to counter the declarations. The ENIA Plan led to a communication campaign with posters on the streets, images for social media and videos[61]. One of the most important condoms manufacturers (Tulipán) also took the opportunity to create an ad campaign about the declaration. They produced images for social media and posters for the public road that read: “They are not made of porcelain. Ours are of latex”[62].

During the debate we heard different arguments presented by groups opposed to reproductive rights that later were replicated. Among them were[63]:

- The assurance that life begins at conception: It was claimed that human life begins at the moment of conception and that, therefore, the State should look after the embryo's or the fetus’ life which deserves to be protected by law. This argument was used by several doctors who affirmed this was a medical absolute.

- Abortion as a cause of maternal death: They tried to deny the numbers and the scientific methods used to collect them and also minimise the amount of deaths caused by unsafe abortions.

- Post-abortion syndrome: these groups manifested that this so-called syndrome has been proven to exist and to have serious consequences on women’s mental health, even when the World Health Organisation (WHO) does not recognise the existence of “post-abortion stress”.

Most of these people used “scientific” sources to endorse their arguments. But upon investigating these sources, we found that most of them were related to academic centres identified with a religious affiliation to demonstrate that abortion has no impact on maternal mortality. On the other hand, even though these groups mention throughout the debate that Sexual Education was essential, conservative movements in Argentina grew stronger and raised barriers to the implementation of ESI and to the access to sexual and reproductive services[64].

After the debate, there was an emergence of strong anti-rights groups especially mobilized around the slogan “Con mis hijos no te metas” (“Do not mess with my children”). These campaigns were based on confronting “gender ideology” and promoting “Yes to Comprehensive Sex Education, no to indoctrination.” During this, they organised marches (generally in front of the National Congress) and also digital campaigns.

On their Facebook page, the Fundación Más Vida, constantly posted photos of dismembered foetuses or other types of grotesque and gruesome as examples of the “horrors of abortions”.

Some examples:

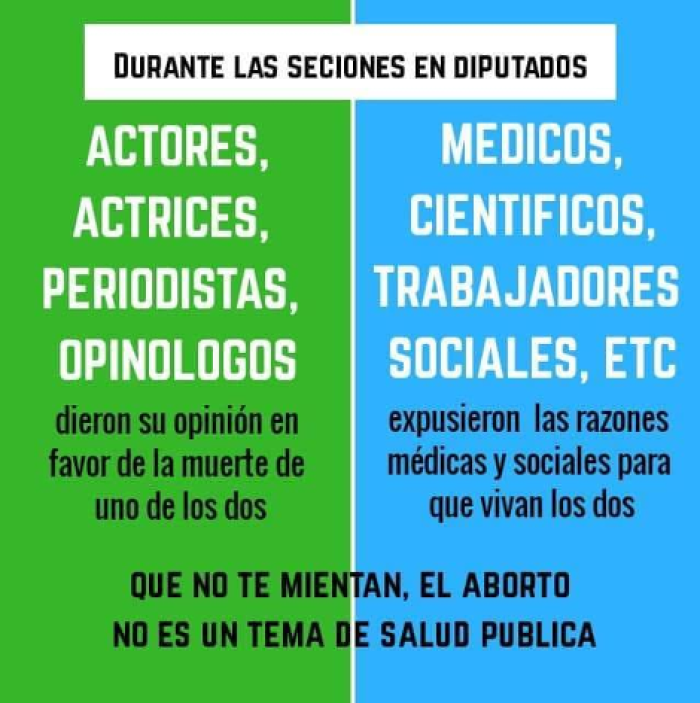

In this image they wrote in the green side (pro-reproductive rights) that the people who spoke at the Congress were: “Actors, actresses, journalists and opinion makers gave their opinion regarding the death of one of them two [referencing the mother and the baby]”, while on the light-blue side (anti-reproductive rights) the people who talked were “Doctors, scientists, social workers presented the medical and social reasons for them both to live [referencing the mother and the baby]”. Underneath it says, “Don’t be lied to, abortion is not a topic of public health”.

This image was used to call for a march on March 7, 2018, while the debate on abortion was on course. It says “I need you. Your help can save me”. The hashtag means “Move To The Congress” (this is a word game between the word “Movida” Move, and “Vida”, Life. Cannot be translated to English). At the bottom it says “With your presence we can stop abortion”.

The image of the foetus was used by this and other organisations throughout the debate.

4. How is the use of technology influencing the reproductive rights space?

The legislative debate on abortion in 2018 in Argentina generated a massive mobilization for women's rights, however, the debate also stirred up violence against the women who expressed themselves in favor of legalisation: “both in public and on social media, women were exposed to assaults, threats, insults and stigmatizing statements.” As a result, Amnesty International has investigated[65] the conditions under which the abortion debate in 2018 has been developed on social media in Argentina[66].

Social media has been an invaluable channel to amplify voices, connect and coordinate strategies during the legislative debate on abortion. “According to the survey carried out by Amnesty International, 28% of women across the country participated in the debate on the legalisation of abortion on social media in 2018, 58% said they agree with the legalisation of abortion.”

Several interviewees referred to the use of Twitter as a complementary platform to the social mobilisations. Twitter became a space to articulate with other actors and sectors of society and a place for political amplification and dissemination of messages. However, the open and public nature of these interactions also mean that the platform can be used to send violent and abusive content. Unlike other social networks, Twitter allows a more public (or less restricted), easy and fast circulation of content.

“According to the survey carried out by Amnesty International, one in three women has suffered violence on social networks in Argentina. Of these, 26% of women victims of violence or abuse on social networks received direct and/or indirect threats of psychological or sexual violence. 59% stated that they were subjected to sexual and misogynistic messages, while 34% received messages with abusive language or comments in general. During the debate over the legalisation of abortion, respondents warned that abusive language increased by 42%; psychological threats of sexual violence, 12%; racist comments, 14%; and homophobic or transphobic comments, 15%. Some of the respondents also stated the impact that this type of violence had on their physical and psychological health. 36% had panic attacks, stress or anxiety and 35% loss of self-esteem or confidence. 34% reported having been afraid of going out and 33% identified having gone through a period of psychological isolation.”

Amnesty International also analysed the type of messages and discourses that fomented forms of violence or hatred. In general, the most relevant grievances refer to murder: “women who promoted the normative change are accused of being murderers and abortion is designated as murder”. Many of the terms comprised violent content. This type of violent discourse was higher in specific cases: the circulation and distribution of violent discourse was not even, but especially focused on some victims.

A report by Mariana Carbajal[67] tells the story of a young woman who in search of information regarding an unwanted pregnancy, arrived at an opposition-led centre. In this centre, the people in charge used intimidation to try to persuade her from terminating the pregnancy.

According to the report, the woman (code name Sabrina) googled “I’m pregnant and I don’t want to continue the pregnancy”. She found a website that offered “some tranquillity”. She got in contact with the people from this organisation who offered an appointment in the following two days.

When Sabrina arrived at the given address (she went with a friend who is a feminist activist), she was asked for her personal data such as her address, ID and phone number, which she gave. This personal information was used later to get in touch with the woman, mainly by calling her to her cell phone to know whether she carried on with the pregnancy or not. She was asked by a man and a woman to enter a different room, alone, and then she was given anti-abortion pamphlets and information. They gave her false information on the dangers of misoprostol and also told her that an abortion was a traumatic experience that would “hunt her forever”.

Sabrina and her friend left the place. She then was able to get in contact with people who eventually helped her with her decision.

According to the report, Sabrina found the website with a simple Google search. She opened one of the first links that appeared and it took her to a Facebook page called Asistencia para la mujer (“Assistance for women”) which showed pictures of women (always fracing away from the camera). The Facebook site had images with phrases such as: “If you have an unwanted pregnancy, don't let fear condition you. Always ask for professional help to ensure your well-being. Write us by private message…” and a cell number (women get in contact via WhatsApp messages). In the Information section of the page, the team behind that site identified itself saying: “We are a professional team that has been accompanying and assisting women over 20 years old. We provide personalized assistance with highly complex equipment…”

The report ends with information on the existence of an “anti-rights network” in Argentina, that seek women with unwanted pregnancies and try to persuade them from having an abortion. The methods they use are attractive and deceiving Facebook pages and a phone number. Once the women arrive at the given address, they show them all type of anti-abortion information and pictures.

What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence in your country? From where do they originate or obtain funding?

In Argentina, dozens of organisations opposed to reproductive rights are actively carrying out a strategy to restrict the access to sexual and reproductive rights, through a wide range of actions: from political advocacy work, legal actions, community work, “help” centres, mobilisations to communication campaigns, in the streets, in the media and on social media[68]. However, there is a clear lack of transparency regarding their connections with other organisations and their funding. With regard to the connections between different organisations, Argentine anti-rights organisations and networks don’t inform very openly about this.

Cuidar la Vida (“Take Care of Life”) is a network that consists mainly of anti-reproductive rights communicators, they pretend to have a regional focus, however their videos, notes and actions are mainly focused on abortion in Argentina. Its website has a section on the different organisations that form part of the network, however, it is only accessible with a log-in. What their website does reveal, is that the videos are uploaded by different organisations or people[69]. On the other hand, Unidad Pro-Vida (“Pro-life Unit”) is a network that includes a wide range of actors and organisations, from the educational, health, business, legal and communication sector, political parties to the even so called anti-choice “feminists”. On the homepage of their website, Unidad Provida has a list with the logos of the organisations that adhered to the network. But on their website they inform very little about specific activities between certain organisations, their references mostly are more general. However, in certain blogs they mention collaborations, such as a protest that they organised with Marcha por la Vida (“March for Life”)[70]. Another network with a greater presence of evangelical groups is + Vida (“More Life”), they don't specify on their website which organisations form part of the network nor the activities they have collaborated on with other organisations. However, on Citizen Go there is evidence of a collaboration with different national organisations that adhered to a “pro-life” march and also some other Latin American organisations[71].

When reviewing the websites of these Argentine anti-rights networks, it’s evident that they often don’t specify which organisations have collaborated on certain activities, nor the funding they have received for it, they rather speak in more general terms (“we have organised...” or “various organisations…”[72]). This lack of information on the links between organisations, complicates the transparency and accountability of these actors and organisations.

In the parliamentary debate on abortion in 2018, one of the anti-reproductive rights discourse strategies was to “cast doubts as regards the interest behind the actions of pro-choice civil society organisations and to inquire about their funding”. In an attempt to discredit speakers and organisations in favor of legalisation, they argued that the pro-choice actors “received financial support from international organisations and foundations that want to impose an imperialist and population control policy in Argentina.” The Argentine media reproduced these questions and inquiries about the pro-choice movement, however, the origins of the funding of the opposition movement was not met with the same interest.[73]

Nonetheless, one foreign organisation with large anti-reproductive rights presence in Argentina is Heartbeat International (HI). This organisation is one of the largest crisis pregnancy centres networks in the United States, and grants funds to Latin American affiliated members, for the development of “crisis pregnancy centres” aimed at persuading women to not interrupt their pregnancies. HI offers its affiliates a range of tools to improve their online presence and extend their reach, inlcuding attracting women that are looking for abortion information to their websites.[74].

At the time of writing, the Heartbeat International Worldwide Directory mentions 34 centres in Argentina from which 21 are affiliates. 20 of the affiliated centres are part of La Merced Vida (in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and the Province of Buenos Aires, Tucumán, Salta, Córdoba and Mendoza) and one affiliated centre is called Salva Una Vida (“Save a life”, in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires). The relationship between HI and the other 13 non-affiliated organisations remains unclear[75].

Another foreign organisation with anti-reproductive rights presence in Argentina is Human Life International (HLI), they have two affiliated organisations in Argentina: Acción por La Vida y La Familia & Profamilia[76]. The exact connection between these local organisations and HLI remains unclear, as does the funding they receive. However, research carried out by The Guardian revealed that HLI channelled over 1.3 million dollars between 2010 and 2015 to anti-reproductive rights partners in Latin America and the Caribbean[77]. Although there is an obvious lack of transparency on the funding, it is likely that HLI gives foreign support to opposition organisations in Argentina.

Ultimately, the organisation Frente Joven (“Young Front”) is another organisation with foreign ties in Argentina. It is a regional youth movement (Argentina, Peru, Ecuador and Paraguay) with conservative and fundamentalist views, and a wide range of activities: from campaigns, community activities to national, regional and international advocacy work[78]. They supposedly receive funds from Alliance Defending Freedom, World Youth Alliance, Hans Seidel Young Leaders Foundation, International Human Rights Group and the Lions Club (Paraguay).

This summary is surely only the tip of the iceberg, the presence of foreign organisations opposed to reproductive rights in Argentina and their funding of local organisations is expected to be much bigger.

Testimony

ELA spoke with representatives from frontline organisations and asked them the following questions:

- What forms of technology do you see deployed in the provision or restriction of reproductive health services or information in your country?

- What foreign or national organisations are actively fighting against implementing reproductive rights that are recognised within human rights law including access to modern contraception, safe abortion, and medically-based reproductive health information in your country?

- What instances of misinformation in reproductive health services have you witnessed, such as online ads, non-medical websites, or other tactics.

- What instances of informal or formalised non-consensual data sharing have you witnessed?

Testimony 1

Name: Damián Levy

Profession: Doctor (Tocogynecologist) and member of the Advocacy Committee of REDAAS - Access to Safe Abortion Network Argentina

Location: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and the Province of Buenos Aires

“In Argentina, phone calls, websites, Facebook and WhatsApp are the main forms of technology used in the provision or restriction of reproductive health services and information”.

Responding to the second question, Damián answered: “An organisation that is very active here is Portal de Belén, and I have also heard of unwanted pregnancy, women's assistance or women's help centres [that are active in Argentina] and an organisation from abroad [with presence in Argentina] is Heartbeat International”.

“The patients that I have attended informed me that when they called the numbers they found online [of organisations opposed to reproductive rights], they ask them to come to the so-called friendly practices where they later threaten and intimidate them to continue with the pregnancy, giving them false information about our current legal framework and the scientifically-based procedures that exist to date, medications or MVA [Manual Vacuum Aspiration], scaring and persuading them to continue the pregnancy”.

“Another method [from the opposition organisations] is to make contact via WhatsApp, they give them a code from Mercado Pago [an online payment system] and say that after the deposit they will send the [abortion] pills, which they never do”.

With regard to the final question, Damián responded that “An article with my name was published without my consent, and also a post on Twitter also without my consent. Both from anti-rights groups”. When asked how that made him feel, he responded “Look, when I first saw it I got angry and annoyed that they lie and modify data and distort information. Everything you see that they published is a lie. After those feelings, I continued my work the same way, with the conviction that it is the right way to do things, and I had no more situations of that kind.”

Testimony 2

Name: Mariana Romero

Profesion: Medical investigator, executive director of CEDES - Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad (“Center for the Study of State and Society”) & founding member of the coordinating group of REDAAS - Access to Safe Abortion Network Argentina

Location: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

“There are many channels [of information], in different formats, brochures, videos, talks, short books, movies, and by different organisations. not all are good, not all respond to the needs of different groups, not all have a gender or rights perspective.”

“Regarding the restriction, it usually is not very explicit: from the omission of the State to have public campaigns to not giving information on the right to abortion to a woman victim of rape. Then there are the more explicit strategies of anti-rights groups, which work more on content, messages... Disseminate information but with an opposite perspective, under the guise of providing accompaniment for women, so that they continue their pregnancy or promote myths about contraception or abortion with medications.”

With regard to the second question, national organisations Mariana knows of are “Más Vida, Fundación Vida en Familia, ACIERA, Red Nacional de acompañamiento a la mujer con embarazo vulnerable [“National Network of support for women with vulnerable pregnancy”], organisations that form part of Cuidar la Vida, JUCUM [For its acronym in Spanish, “Youth With a Mission”] and Grávida.”

There are several instances of misinformation in reproductive health services that Mariana has witnessed, such as “The presentations in the 2018 debate on the IVE bill [For its acronym in Spanish, “Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy” Bill] in Argentina, but also in brochures for women, videos, TV programs, participatory workshops with women and websites or helplines for pregnant women.”

With regard to the instances of informal or formalised non-consensual data sharing, there are cases where anti-rights actors “shared clinical stories without omitting personal data, news in newspapers, emails referring to a situation where the women's name and last name are indicated.”

Testimony 3

Name: Ingrid Beck

Profession: Feminist journalist and communicator. Writer and founder of Revista Barcelona

Location: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

“The main network to distribute false information is WhatsApp. Followed by the rest of the social media. The list would be WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter. Essentially they use them to raise doubts and false information about human rights defenders, spread anti-science discourse, anti-scientific evidence, and conservative and reactionary discourse. I think that all those messages come from false news that have no scientific sources or simply fake news that could not even be credible, but as they get replies or are distributed, they become credible.

Sometimes they are built in a way that looks like they are real and other times they are absolutely crazy, but because they work with the confirmation bias they make that news credible”.

“Anti-rights groups also have their own media or make alliances with some big real media. And these media outlets mix fake news with real news. With which, what they do is confuse. They also attack those who promote sexual and reproductive rights. They attack different defenders in an organised manner with the clear objective of disciplining and threatening them. They say threats, offences, insults, though these threats in general do not become reality”. When asked which organisation she could identify, Ingrid said: “It is difficult for me to identify organisations. But I do know of the existence of the Unidad Pro-Vida [“Pro-life Unit”] that brings together many civil society organisations and some evangelical and very conservative Churches of the Catholic Church. There is a hub there. There are also some communicators with many followers and very good personal marketing like Agustin Laje or Mariano Obarrio. Opinion leaders, and I think some messages get distributed from them. But it seems to me that they also respond to some organisations that we have not yet identified. Media centres. And there are some messages that clearly come from other countries, such as the “Con mis hijos no te metas” [“Don’t mess with my children”] campaign and the supposed gender ideology messages that come from other countries. These are not campaigns that were born here in Argentina, but were imported during the abortion debate and now they continue. Right now with the Covid-19 they are imposing anti-science speeches.”

Regarding the third question, Ingrid mentioned: “I can think of one example of something they did, I think it was during the abortion debate in Argentina. When Myriam Bregman was a legislator from the City of Buenos Aires they published a story that said that she had presented an amendment to the Legislature to stop saying that power plugs were male or female. It was absolutely delusional news, but it spread so widely that Bregman finally had to step out and declare that this was not true. So the capture of a WhatsApp message became a news story. What also happens is that some of that news is raised by the serious media and then transformed into real news”

“When Marisa Graham was appointed Ombudsperson of Children and Adolescents, there was an organised attack by anti-rights groups, on Twitter especially. The attack showed that it was absolutely premeditated, prepared. They were accounts that were inactive and activated at that time, accounts that had been used for the last time to create some anti-Chavista Trending Topic. These messages clearly came from an organisation or a call centre. There are some people, there are some original messages from people, and then the rest are accounts created to generate a Trending Topic and discipline, which I think is the goal as well.”

“Also, when the abortion debate was over, they had taken a fake image of Mafalda with the light blue scarf and said that Quino was anti-rights. Quino's relatives had to come out to clarify that it was not true and that Mafalda was in favour of women's rights. We also know that what is fixed in society is the first premise and the denial often fixes the premise rather than denying it. There was another news message that went quite viral that had to do with the last National Meeting of Women that said that the feminists had burned the cathedral and a dog. It was false, they used pictures of other things. They built fake news. Another news article, which spread worldwide and was replicated here by a site called El disenso, from the province of Cordoba, a website that is known to publish fake information, particularly against feminists and the Ni una menos movement, and they have a lot of replica, was that vaccines were being made with the remains of abortion fetuses. It was a horrible combination of anti-vaccines and anti-abortion discourses.”

Ingrid also mentioned regarding the opinion makers: “Laje published a book and tours the world and Latin America transmitting the anti-rights message. They also have many young followers. One tends to think that these thoughts come from older people and the truth is that they do not, they cross all ages. Laje's followers are almost all young men. So they get into action, into real life and they are distributing their messages everywhere. In northern Argentina they have many followers and it is not just Albino who is going to give talks, they have their own anti-rights representatives everywhere, in governments, in the judiciary. I give the example of Laje because he is an opinion leader who emerged from social networks.”

“There is something that seems central to me and that is that they are a threat to democracy and we can see it clearly now, also in the midst of a pandemic, where the representatives of the great politics share this anti-science discourse. People like Mexican president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, Brasilian president Jair Bolsonaro or US president Donald Trump, who is also an influencer on social media.”

Testimony 4

Name: Juan Pablo Poli

Profession: Sociologist, member of the Red Nacional de jóvenes para la salud sexual y reproductiva (“National Youth Network for Sexual and Reproductive Rights”)

Location: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

“The subject of technology is a great pending topic. This is what we have been asking for for a long time, incorporating new technologies and the new means and forms of communication for the adolescents for the provision of information. For example, if you enter the page of the Ministry of Health, you will find information about contraceptive methods for example, but not in a friendly, dynamic, simple, didactic way, within reach. And also it happens that in many important websites or websites of organisations with certain relevance there is a lot of erroneous information. What circulates on the web in general is false information or is information that reproduces a myth or a stereotype or a certain misconception or old information. So the topic of information on the web is an issue.”

“I don't know if the problem is so much information restriction as misinformation distribution. I do not think that today it is so feasible to restrict information. If you search for some topic, you’ll find information, but you can find erroneous information. You can search for information about the Legal Termination of Pregnancy, and you’ll find different things. You can find fairly good information and lousy information from anti-rights groups. But restricting information today is almost impossible with all the means out there. But there is a lot of misinformation on the part of people and of groups that do not do it with bad intention but are victims of general misinformation and trying to help, fall into errors or erroneous information. Then there are the groups that are moved by interests and resources, which are the most dangerous ones I think. They are purposely misinforming with a very clear objective”.

Regarding the second question, Juan Pablo says: “The first one that comes to mind is the church, which is the most influential organisation in the world and that has risen up with these family issues, against sexual and reproductive rights. Later, to a lesser extent, other civil society organisations or social organisations have appeared, such as the entire Con mis hijos no te metas (“Do not mess with my children”) movement, which has been widely disseminated in Latin America and especially South America. And thirdly, something that also worries me a lot is that some of those sectors have penetrated so deeply into the political organisation and party structure of some countries. And this we have seen here. Here in the last presidential election there were parties created and their platform and their action is to be against the legalisation of abortion. Nothing more than that. And there are legislators who have been elected from that platform as if their only task is to legislate on the legalisation of abortion. And they have a considerable percentage of votes, it does not matter if only at the provincial level and nothing more. That worries me a lot.”

Regarding the disinformation, Juan Pablo says: “One sometimes comes across platforms or official pages with grave errors. And sometimes it is not so much the error in the information but an error in the perspective. some websites are still very binary, very heteronormative, very machista [“macho”] even on these issues, which is unforgivable. There are thousands of instances of disinformation, because, for example, in social networks one can say what they want and especially in this time when people share things without properly reading them. Added to the natural disinformation that people have because these topics are generally not discussed in homes, or in families, or in society in general, or in the media. So it is very counterproductive. And then the anti-rights groups have been able to exploit social media exponentially, perhaps even better than pro-choice groups. Their handling of social media and communication is really impressive. They are very cunning.”

According to him other instances are: “the interpersonal disinformation, that of myths, the information that is passed and transmitted and achieves a level of consensus that takes it for granted but is not based on any real or scientific concept. I teach many workshops on reproductive health and rights, contraception, and about the subject of contraception there are a thousand myths and they are transmitted among friends, siblings and so on. So I think you also have to interfere with that transmission, which is basically giving good information. The problem is that not everyone has access to truthful information.”

“Another point regarding perspective, is medical consultations. In general, doctors, gynaecologists or generalist practitioners, have quite machista [“macho”] perspectives or adult centred perspectives that don't work with youngsters. I know this from friends who tell me that they are going to be treated and still give little information or do not explain about the contraceptive methods they could use. Medical training is still a long way from progress.

The teachers too. It is very common that they come across questions from their students who do not know how to answer, due to the same lack of information. But sometimes with the good intention of responding, they reproduce the same myths and concerns that young people have. Caused by the same fact of not having the correct information. I think there are many areas of disinformation.”

1. REDAAS. (2018). Argumentos para el debate sobre aborto en Argentina. Buenos Aires, March 3, 2018.

2. Ramón Michel, A. (2009). Aproximación al fenómeno de inaccesibilidad del aborto no punible.

3. Argentine Supreme Court of Justice, case “F.A.L. s/ medida autosatisfactiva,” File N.º 259/2010, Volume: 46, Letter: F, Judgment of March 13th, 2012.

4. Ramón Michel, A. & Ariza Navarrete, S. (2018). La legalidad del aborto en Argentina. N°9 collection of documents REDAAS. REDAAS. Buenos Aires, 2018.

5. Leone, C. & Reingold, R. (2018). Overcoming barriers to legal abortion in Argentina. O’Neill Institute. Available at: https://oneill.law.georgetown.edu/overcoming-barriers-to-legal-abortion-in-argentina/

6. Página 12. (2019). El texto completo de la resolución del Protocolo ILE publicada en el Boletín Oficial. El País. Available at: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/236351-el-texto-completo-de-la-resolucion-del-protocolo-ile-publica

7. Province of Buenos Aires, Entre Ríos, Jujuy, La Pampa, La Rioja, Misiones, San Luis, Santa Fe & Tierra del Fuego. See annex 1.

8. Corrientes, Formosa, San Juan, Santiago del Estero, Tucumán & Mendoza. See annex 1.

9. Ramón Michel, A. & Ariza Navarrete, S. (2018). La legalidad del aborto en Argentina. N°9 collection of documents REDAAS. REDAAS. Buenos Aires, 2018.

10. See the action of protection presented against the protocol: http://scw.pjn.gov.ar/scw/viewer.seam?id=0wCCienzB94A2BIJfHuTmX5f%2BkcTeMTXIb%2FGxFDysgQ%3D&tipoDoc=despacho&cid=5176105

11. Abogados Y Abogadas del NOA en Derechos Humanos y Estudios Sociales (ANDHES), et al. (2018). Presentación internacional. Acceso al aborto en la Argentina.

12. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

13. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

14. Bistagnino, P. (2020). Proyecto de aborto legal: las 5 incógnitas sobre las que están puestos todos los ojos. Infobae, Sociedad. Available at: https://www.infobae.com/sociedad/2020/03/03/proyecto-de-aborto-legal-las-5-incognitas-sobre-las-que-estan-puestos-todos-los-ojos/

15. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

16. Abogados Y Abogadas del NOA en Derechos Humanos y Estudios Sociales (ANDHES) et al. (2018). Presentación internacional. Acceso al aborto en la Argentina.

17. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

18. As can be seen on the website of Gravida they have several “help centres” in more conservative and often poorer areas of the country. The same can be concluded from the centres that La Merced Vida has according to the Heartbeat International directory.

19. Campana, M. (2020). Políticas Antigénero en América Latina: Argentina. Observatorio de Sexualidad y Política (SPW).

20. Karstanje, M., Ferrari, N. & Verón, Z. (2019). Post-truth and Setbacks. An Analysis of Anti-choice Groups’ Discourse Strategies during the Legislative Debate on Abortion in Argentina. REDAAS. December 2019.

21.Salomé Fernández Vázquez, S. & Brown, J. (2019). From stigma to pride: health professionals and abortion policies in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27:3, p. 65-74.

22.Drovetta, R., I. (2018). Profesionales de la salud y el estigma del aborto en Argentina. El caso de la “Red de profesionales de la salud por el derecho a decidir”.

23. In Argentina, the freedom of conscience is translated in articles 14 and 19 of the National Constitution (CN), which guarantee freedom of religion and conscience, and actions that do not harm third parties. We also find this right guaranteed in human rights covenants with constitutional rank, in accordance with article 75, paragraph 22 of the National Constitution. With regard to the conscientious objection of health professionals, law No. 26,130, which establishes the regime for surgical methods of contraception, is the first law at national level that recognises the right to conscientious objection of health professionals, however only in cases of surgical contraception (such as tubal ligation and vasectomy). At the provincial level, various provincial sexual and reproductive health regulations have included conscientious objection in their legal framework. However, there are limits and requirements in place regarding when and how it can be used (as started in the “F., A.L.” ruling and the national abortion protocol). See more (in Spanish): http://www.salud.gob.ar/dels/entradas/la-objecion-de-conciencia.

24. Drovetta, R., I. (2018). Profesionales de la salud y el estigma del aborto en Argentina. El caso de la “Red de profesionales de la salud por el derecho a decidir”

25. Ramón Michel, A. & Ariza Navarrete, S. (2019). Usos imprevistos y respuestas a la objeción de conciencia en el aborto legal. REDAAS & Ipas, Buenos Aires, 2019.

26. Luchetti, G. & Ramón Michel, A. (2019). Misoprostol. Un medicamento esencial. N°10 collection of documentos REDAAS. REDAAS. Buenos Aires, august 2019.

27. Vallejos, S. (2019). Aborto: suspenden la venta en farmacias de misoprostol para pacientes. La Nación, Sociedad. Available at: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/sociedad/aborto-suspenden-venta-farmacias-misoprostol-pacientes-nid2313393

28. Unidiversidad. (2019). Seis de cada diez argentinas usa anticonceptivos modernos. Sociedad. Available at: http://www.unidiversidad.com.ar/seis-de-cada-diez-argentinas-usa-anticonceptivos-modernos

29. Argentina.gob.ar. (2020). Métodos anticonceptivos. Available at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/saludsexual/metodos-anticonceptivos

30. Huésped. (2020). Acceso a Métodos Anticonceptivos. Available at: https://www.huesped.org.ar/informacion/derechos-sexuales-y-reproductivos/tus-derechos/acceso-a-metodos-anticonceptivos/

31. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

32.Romero, M., E. (2019). La causa por la píldora del día después espera fallo del TSJ desde hace 10 años. Perfil, february 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.perfil.com/noticias/cordoba/la-causa-por-la-pildora-del-dia-despues-espera-fallo-del-tsj-desde-hace-10-anos.phtml

33. Idem.

34. See the action of protection of Partido Demócrata Cristiano and Ernesto Lamuedra, received on november 25, 2019 (in Spanish): http://scw.pjn.gov.ar/scw/viewer.seam?id=7X5uDgMxp9CG6e0debIxrbn3jE7DghIXn65%2BAiakSEU%3D&tipoDoc=despacho&cid=5176105

35. Bianco, M. (2015). Atención y costo de la salud sexual y reproductiva en Argentina. FEIM. Buenos Aires, december 2015.

36. Idem.

37. See law No. 26,150 (in Spanish): https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/ley26150.pdf

38. Argentina.gob.ar. (2020). Elaboración de materiales educativos. Available at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/educacion/esi/historia/materiales.

39. Diario Digital Femenino. (2019). ¿Cuál es el estado de implementación de la ESI a casi 13 años de la sanción de la ley 26.150? Available at: https://diariofemenino.com.ar/cual-es-el-estado-de-implementacion-de-la-esi/

40. InfoCatólica. (2018). Escuelas católicas rechazan proyectos de «educación sexual integral» en Argentina. Available at: https://www.infocatolica.com/?t=noticia&cod=33136

41. Karstanje, M., Ferrari, N. & Verón, Z. (2019). Post-truth and Setbacks. An Analysis of Anti-choice Groups’ Discourse Strategies during the Legislative Debate on Abortion in Argentina. REDAAS. December 2019

42. Salvemos Las Dos Vidas (“Let's Save The Two Lives”), La Ola Celeste (“The Light Blue Wave”), Docentes Por La Vida Y La Familia (“Teachers for Life and the Family”) & Somos Más Argentina (“We are More Argentina”).

43. See more at the #ConMisHijosNoTeMetas website: https://conmishijosnotemetas.com.ar

44. Bianco, M. (2015). Atención y costo de la salud sexual y reproductiva en Argentina. FEIM. Buenos Aires, december 2015.

45. Ramos, S., Bergallo, P., Romero, M. & Arias Feijoó, J. (2009). “El acceso al aborto permitido por la ley: un tema pendiente de la política de derechos humanos en la Argentina”, en Derechos humanos en Argentina. Informe 2009. Buenos Aires, 2009. P. 451-491.

46. Argentina.gob.ar. (2020). Métodos anticonceptivos. Available at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/saludsexual/metodos-anticonceptivos

47. Abogados Y Abogadas del NOA en Derechos Humanos y Estudios Sociales (ANDHES), et al. (2018). Presentación internacional. Acceso al aborto en la Argentina.

48. Bianco, M. (2015). Atención y costo de la salud sexual y reproductiva en Argentina. FEIM. Buenos Aires, December 2015.

49. ELA - Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género. (2018). Análisis del proyecto de presupuesto 2019 desde una perspectiva de género: avances y retrocesos para la igualdad.

50. IDEP SALUD. (2019). Subejecución del presupuesto nacional de salud 2019. Un instrumento más del ajuste. Available at: http://idepsalud.org/subejecucion-del-presupuesto-nacional-de-salud-2019-un-instrumento-mas-del-ajuste/

51. Bianco, M. (2015). Atención y costo de la salud sexual y reproductiva en Argentina. FEIM. Buenos Aires, December 2015.

52. Idem.

53. UNO Entre Ríos. (2019). Numerosas obras sociales evaden la entrega gratuita de anticonceptivos. Section La Provincia. Available at: https://www.unoentrerios.com.ar/la-provincia/numerosas-obras-sociales-evaden-la-entrega-gratuita-anticonceptivos-n1755160.html

54. Law number 26.150, Programa Nacional de Educación Sexual Integral (In English, National Program of Comprehensive Sexual Education). Available at: http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/120000-124999/121222/norma.htm.

55. Official website of the Plan ENIA: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/planenia.

56. UNFPA (2020). Consecuencias socioeconómicas del embarazo en la adolescencia en Argentina. March, 2020. Available at: https://argentina.unfpa.org/es/Consecuencias-socioeconomicas-del-embarazo-en-la-adolescencia-en-Argentina

57. REDAAS. (2019). From Clandestinity to Congress. An Analysis of the debate on the legalization of abortion in Argentina. June, 2019.

58. Exposition by Abel Albino at the Senate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7dUgw6fZLA&t=2555s (in Spanish, quote at time 42:00). Also: Gonzalez, A. (2018). Por qué Abel Albino habló de la porcelana en sus falsos dichos sobre el HIV. Perfil, Section Sociedad, July 26th, 2018. Available at: https://www.perfil.com/noticias/sociedad/por-que-abel-albino-hablo-de-la-porcelana-en-sus-falsos-dichos-sobre-el-hiv.phtml

59. Infobae. (2018). El ministro de Salud de la Nación repudió a Abel Albino: “Dijo disparates y barbaridades temerarias”. Section Política, July 26th, 2018. Available at: https://www.infobae.com/politica/2018/07/26/el-ministro-de-salud-de-la-nacion-repudio-a-abel-albino-dijo-disparates-y-barbaridades-temerarias/

60. Filo.news. (2018). El repudio de la Fundación Huésped ante los dichos de Abel Albino. Section Actualidad, July 25th, 2018. Available at: https://www.filo.news/actualidad/El-repudio-de-la-Fundacion-Huesped-ante-los-dichos-de-Abel-Albino-20180725-0054.html

61. Institutional video of the National Plan for the Prevention of Unintended Pregnancy in Adolescence: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gl-Temz2HKA&t=1s

62. Infocielo. (2018). “Doctor, no se preocupe…”: la ingeniosa respuesta de una marca de preservativos a Abel Albino. Section Sociedad, July 26th, 2018. Available at: https://infocielo.com/nota/94016/doctor_no_se_preocupe_hellip_la_ingeniosa_respuesta_de_una_marca_de_preservativos_a_abel_albino/

63. REDAAS. (2019). From Clandestinity to Congress. An Analysis of the debate on the legalization of abortion in Argentina. June, 2019.

64. Karstanje, M., Ferrari, N. & Verón, Z. (2019). Post-truth and Setbacks. An Analysis of Anti-choice Groups’ Discourse Strategies during the Legislative Debate on Abortion in Argentina. REDAAS. December, 2019

65. Corazones verdes: violencia online contra las mujeres durante el debate por la legalización del aborto available at: https://amnistia.org.ar/corazonesverdes/files/2019/11/corazones_verdes_violencia_online.pdf

66. Amnesty International conducted a survey on online violence against women in Argentina. Based on 1,200 women, ages 18 to 55, surveyed across the country. They also conducted a qualitative analysis with an in depth study of the testimonies of 18 women, - including legislators, activists, actresses, journalists and writers - who have had a leading role in the debate on abortion in Argentina. Finally, a quantitative analysis of a wide selection of conversations and interactions was carried out on Twitter: 332,112 tweets and 24 profiles were selected that exhibited significant activity during the public debate on abortion in 2018.

67. Una visita a una página antiderechos camuflad available at: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/220128-una-visita-a-una-pagina-antiderechos-camuflada

68. To learn more about the social media presence of the anti-choice organisations, see annex 2 - Twitter accounts of some anti-choice groups.

69. For example: Buena Data (“Good Data”), Radio #VozPorLaVida (“Radio #VoiceForLife”); Marcha por la Vida (“March for Life”) & Médicos por la Vida (“Doctors for Life”).

70. See more (in Spanish): https://www.unidadprovida.org/post/marcha-a-olivos

71. See more (in Spanish): https://www.citizengo.org/es-ar/177847-marcha-virtual-por-vida?utm_source=tw&utm_medium=social&utm_content=typage&tcid=67992769

72. See for example (in Spanish): https://cuidarlavida.org/news/organizaciones-repudian-el-bozal-legal-aplicado-a-medico

73. Karstanje, M., Ferrari, N. & Verón, Z. (2019). Post-truth and Setbacks. An Analysis of Anti-choice Groups’ Discourse Strategies during the Legislative Debate on Abortion in Argentina. REDAAS. December, 2019

74. Carbajal, M. (2019). Los anti derechos usan big data. Página 12, Sociedad. Available at: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/208961-los-antiderechos-usan-big-data

75. In-house study of the Heartbeat International Worldwide Directory: https://www.heartbeatinternational.org/worldwide-directory

76. In-house study of the Spanish website of Human Life International (“Vida Humana Internacional”): http://vidahumana.org/bk-vhi/organizaciones-afiliadas/item/54-argentina

77. Guardian. (2017). US groups pour millions into anti-abortion campaign in Latin America and Caribbean. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/oct/26/us-groups-pour-millions-into-anti-abortion-campaign-in-latin-america-and-caribbean

78. In-house study of the website and social media from the organisation