Q&A South African Constitutional Court amaBhungane case

The Constitutional Court of South Africa declared that bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre is unlawful and invalid.

PI’s interventions contributed towards a historic decision from the Constitutional Court of South Africa, which ruled that bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre is unlawful and invalid. This decision held that secret and unchecked surveillance practices used by South African authorities must be explicitly stated in law so they can be considered and debated.

What’s the ruling all about?

The Constitutional Court of South Africa in a historic judgment declared that bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre is unlawful and invalid. Furthermore, the Constitutional Court found that the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA) 1) was deficient in failing to provide at least a post-notification procedure for subjects of interception; 2) failed to ensure the independence of the designated judge; 3) failed to provide appropriate safeguards when an order was granted ex parte; 4) lacked appropriate procedures to be followed when state officials examine, copy, share, sort through, use, destroy and/store data obtained from interceptions; and finally, 5) failed to prescribe special procedures for cases when the subject of surveillance was either a practising lawyer or a journalist.

How did we get here?

The case was brought by amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism NPC, and its managing partner, Sam Sole, after evidence came to light that the latter had been a target of government surveillance under the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA). In its legal action, amaBhungane challenged several aspects of the RICA legislation, including bulk surveillance powers.

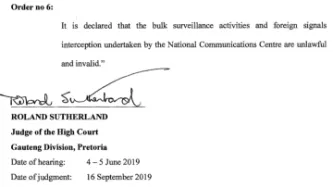

In 2019, the High Court sided with the claimants, ruling that bulk surveillance carried out by intelligence agencies under RICA was unlawful. The High Court judgment was appealed to South Africa’s Constitutional Court.

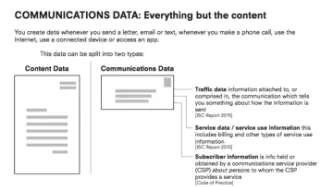

Following up on our joint submission before the High Court, Privacy International submitted an amicus curiae before the Constitutional Court that provided evidence that mandatory blanket retention of all users' communications data – information about when, where, how and with whom they communicate – violates international human rights law and it is therefore unconstitutional. It further supported that indiscriminate bulk interception of foreign signals – which translates to all internet traffic passing through South Africa – also infringes the right to privacy. R2K provides additional arguments regarding the notification of interception and the independence of the judges authorisation an interception, as necessary requirements for any interception of personal electronic communications to be lawful.

Wait - how do intelligence agencies come about this mass data in the first place?

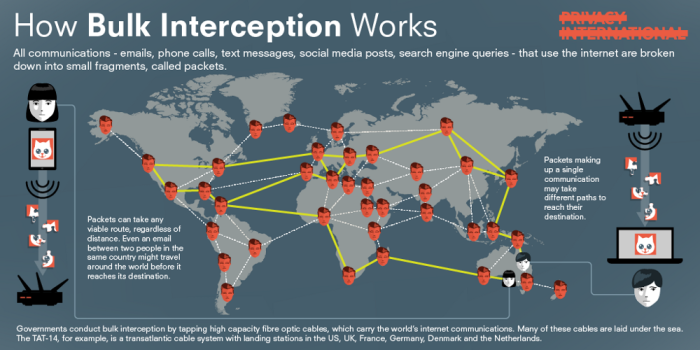

How does bulk interception work?

The internet is basically a massive network of connected computers speaking to one another. To read this webpage, for example, your device has to ‘ask’ Privacy International’s server to show you this content, which it typically sends along telecoms cables (though depending on your network, sometimes satellites). Of course, you could be reading this anywhere in the world: in that case, this internet traffic is likely travelling along international underwater cables at lightspeed - indeed, because of the way the internet works, sometimes it might be quicker for this internet traffic to travel across several continents, even if you’re reading this in the UK which is where PI is based! Because a lot of the online services people use are also based in the US (think Amazon or Google), it means that if someone in South Africa, or indeed anywhere else in the world, were to visit a US website or app to use them, their traffic would also travel along these international cables. What this means is that a huge proportion of global internet traffic is travelling along these submarine cables.

In South Africa, these major cables carry internet traffic into and out of the country - and it’s them which the intelligence agencies are tapping. But instead of tapping them as they might with a phone line (ie wiretapping someone’s calls if there’s some specific suspicion that that person is engaging in criminal activity) they’re collecting it all - the internet traffic of millions of people. This is what’s known as ‘bulk interception’.

This kind of collection amounts to mass surveillance. For more information on how bulk interception works see here.

What is data retention?

Whether it’s your local supermarket, your phone service provider or a ride-hailing app, these days companies hold huge amounts of data about you. Human rights requires governments to protect your privacy. Among other obligations, companies are asked to keep the length of time data is stored to a strict legal minimum. That’s a wise protection. Because the longer data is kept, the more likely it is that it can be abused, lost, stolen, shared, used to profile and even track you. Some governments, including the South African one, have (unwisely) forced companies to keep hold of your data for much longer. This is called mandatory data retention.

When such data retention is general and indiscriminate, it means that sensitive data will be kept, even though you’re not suspected of any crime. Basically, it’s a form of mass surveillance. Like other mass surveillance, this means we’re all treated as suspects. In a democracy, the principle is meant to be ‘no suspicion, no surveillance’. The police and other state bodies already have massive powers. General and indiscriminate data retention is a step too far, and a disproportionate threat to our privacy.

Why is this judgment relevant?

Even after the Snowden disclosures, governments refused to acknowledge the existence of these programmes, which could potentially put each and every one of us under the microscope of state surveillance. This judgment will influence not only the developments in South Africa but sets a precedent for other countries to follow: now we have a resounding proof that these practices exist, and a strong judicial statement that such practices interfere with our privacy and should be explicitly and clearly regulated. It constitutes a positive step towards transparency and regulation.

We have analysed the relevance of this case here.

So is it all good news?

The Constitutional Court declared that the mass surveillance regime in South Africa was unlawful and invalid because such intrusive powers could not be read into other provisions or be construed as implied by the law. The Constitutional Court held that the broad terms of the National Strategic Intelligence Act are not suffice to justify the bulk surveillance regime. The Court was not persuaded by the South African intelligence authorities’ plea that other states have similar practices.

It was not necessary for the Constitutional Court to decide whether a law permitting bulk interception would be constitutionally compliant, as it concluded that there was no such law to begin with. However, the High Court made it pre-emptively clear in its ruling that it would not automatically accept the constitutionality of any such law, declaring that the need for clarity was especially acute “when the claimed power is so demonstrably at odds with the Constitutional norm that guarantees privacy.” The Constitutional Court, which highlighted the unique relevance of the right to privacy in light of South Africa’s history, furthermore didn’t exclude the possibility for such a case to arise in the future.

Ok, so what happens next?

Extending the two-year period given by the High Court, the Constitutional Court gave three years for Parliament to cure the constitutional defects it identified in RICA.

Until that Parliamentary review takes place, temporary provisions - referred to as ‘interim relief’ - inserted into RICA by the High Court and approved by the Constitutional Court will apply regarding post-surveillance notification and surveillance of lawyers and journalists.

In the meantime in Europe…

In Europe, on 6 October 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union, EU’s highest court, found that the UK, French and Belgian mass surveillance regimes must be brought within EU law and respect privacy, even in the context of national security. All three cases, one of which was brought by PI, have returned to national level putting the surveillance regimes under further judicial scrutiny. We are still waiting for the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights to pronounce on the legality of bulk interception in the United Kingdom.

In a landmark judicial review ruling handed down in January 2021, the English High Court echoed the South African Constitutional Court’s reasoning: legislation cannot be interpreted as having intended to override fundamental rights in the absence of explicit, clear language.

Got it. How can I help?

Having strong laws and technology which protect privacy is incredibly important, but the most important thing is that people are aware of the issues and are able to influence powerful companies and governments. You can read more about the case.

To keep up to date on the case and all our work, you can sign up to our mailing list here - don’t worry, you can choose the topics you are most interested in… and we take proper care of your data!

As we are a charity with limited funds, any support you can give us through a donation would be most appreciated - you can do so here.

To reiterate however, to really ensure that we don’t sleepwalk into a world of ubiquitous state and corporate surveillance, it is essential that people put pressure on governments and corporations - so if there’s one thing you can do, it’s make your voice heard!