Spanish elections under the new data protection law: use of personal data by political parties?

This image was found here.

Spain is holding a national general election on April 28 (its third in four years). Four weeks later Spaniards will again go to the polls to vote in the European Parliament elections. At Privacy International we are working to investigate and challenge the exploitation of people’s data in the electoral cycle including in political campaigns. This includes looking at the legal frameworks governing the use of data by political parties and their digital campaigns.

The elections in Spain are the first taking place in the country since Spain updated its national data protection act in December 2018, in accordance with the new General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), which has resulted in increased scrutiny of the use of data by political parties.

A legal loophole for political parties

The new Spanish data protection law (which implements the derogations of, and applies together with, GDPR) has been the subject of controversy due to provisions concerning the use of personal data related to political opinions - a special category of personal data according to GDPR, and thus subject to a high level of protection. In particular, the Spanish implementation of GDPR includes an amendment to electoral law that allows political parties to collect and use personal data relating to people’s political opinions for their political activities during the electoral period. This includes personal data from websites and publicly available sources. Furthermore, the amendment permits political parties, coalitions and electoral groups to send political propaganda via email, social media, phone messaging apps and other digital media. These provisions provide an exemption, that negates the need for political parties to seek individuals’ explicit consent leading to concerns around data exploitation. Exemptions in data protection law for political parties in the UK and Romanian laws have also raised concerns.

Challenging the loophole – the AEPD and Ombudsman take action

The legal office of the Spanish Data Protection Agency (“AEPD”) issued a first opinion on the law in December 2018. In this report, the AEPD argued for a very restrictive interpretation of the amendment. In March 2019, after a period of public consultations, the AEPD published a circular establishing the criteria with which it will evaluate the legality of campaign activities undertaken by political parties regarding the collection and use of personal data related to political opinion and the distribution of electoral propaganda to voters through digital means. In this circular the AEPD: establishes that the data processing relying on this exemption must be limited to the period of the electoral campaign and to purposes relevant to the campaign; prohibits the sharing of data with third parties; forbids the use of big data analytics to infer political opinion that has not been freely and explicitly shared; restricts the data collection to public sources available to anyone (thus excluding data shared with a limited number of people, e.g., “friends only” in social media); and deems unacceptable the inference of political ideology through the elaboration of individual profiles as well as the microtargeting of voters. Whilst there is a clear intention to protect the use of personal data as part of the democratic process, questions have also been raised as to how these requirements will be implemented in practice, for example, in relation to legitimate political speech and the absence of a clear definition of microtargeting.

In parallel, the Spanish Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo) has submitted an appeal to the Constitutional Court claiming that the amendment creates legal uncertainty and violates various articles of the Spanish Constitution, including those that protect the rights to ideological freedom and political participation.

Political parties have reacted to these developments with concern, particularly given the AEPD’s warning that it could fine parties with up to 20 million euro for data protection violations. News reports indicate that several parties pulled their Facebook advertising due to uncertainties around the legality of political ads.

The implementation of the Spanish AEPD’s guidance, any subsequent enforcement and the outcome of the Ombudsman’s case will have implications for the use of data in political campaigning in Spain and further afield.

How parties communicate with voters and what they say they do with their data

In this context, we have looked at what political parties in Spain say about their use of personal data and how they use social media to reach voters. Our scope is restricted to the five main nation-wide parties, namely: Partido Socialista Obrero Español (“PSOE”), Partido Popular (“PP”), Ciudadanos (“C’s”), Unidas Podemos (”Podemos”) and VOX. The review is also limited in terms of depth: without access to the backend IT systems used by parties it is not possible to determine the full extent of their data collection and processing practices, for example, whether they purchase datasets from data brokers to enrich their own databases, whether they use big data analytics to infer political ideology and elaborate detailed individual profiles for voters, and whether they use those profiles for (micro)targeting their messages and conducting campaign activities. Despite these limitations, our review sheds some light on digital campaigning by political parties in Spain, highlighting commonalities and differences in their approach.

Social media engagement with voters

In terms of social media engagement all parties use roughly the same platforms, though they differ in the emphasis on one or another platform as well as in their success engaging followers. Table 1 shows the number of followers that each party has attracted (as of 10 April 2019) in the platforms where they are present.

|

|

|

|

|

YouTube |

Telegram |

Flickr |

|

|

PSOE |

165 K |

662 K |

44 K |

16 K |

3,2 K |

< 1 K |

< 1 K |

|

PP |

199 K |

700 K |

60 K |

13 K |

2,4 K |

< 1 K |

1,9 K |

|

C’s |

332 K |

510 K |

76 K |

38 K |

2,5 K |

< 1 K |

4 K |

|

Podemos |

1231 K |

1360 K |

113 K |

79 K |

8,9 K |

< 1 K |

- |

|

VOX |

287 K |

224 K |

234 K |

115 K |

9,4 K |

< 1 K |

< 1 K |

Table 1: Thousands (K) of followers per party and per media platform (10 April 2019)

As we can see in the table, Facebook and Twitter are the platforms through which parties are able to reach the largest number of voters, followed by Instagram and YouTube. Other media such as Telegram or LinkedIn allows them to reach a comparatively much smaller number of people. Even though they all list Flickr as one of the platforms where they are present, they at best have a few hundred followers in that platform. In addition to the media included in Table 1, Podemos boasts more than half million voters subscribed to their web participation portal and 15 K followers on Reddit.

Depending on the platform considered, Podemos and VOX dominate in terms of social media following. While they represent opposites in terms of ideology, both are usually characterized as populist movements situated farthest from the center of the political spectrum – with Podemos being a left-wing party and VOX a right-wing party. Both are also the newest of the five parties considered. Podemos was founded in 2014 and obtained representation for the first time in the past European Parliament Elections. Podemos is currently the third force by number of MPs in the Spanish Parliament. VOX was founded in 2013 but did not succeed in obtaining representation until the regional Andalusian elections of 2018. They currently hold no seats in the Spanish Parliament but are expected to obtain significant representation in the upcoming April election.

In contrast, traditional parties with a long history of institutional representation, notably PSOE and PP, attract significantly less following in social media and trail the other three parties in all platforms except for Twitter, where they are the second and third force after Podemos.

While the social media platforms included in Table 1 reveal the number of followers for the considered parties, other digital media are less transparent. In particular, it is not possible to know the number of voters that receive information from parties via WhatsApp or specific party apps.

|

|

WhatsApp Personal |

WhatsApp Broadcast |

App |

|

PSOE |

- |

- |

miPSOE |

|

PP |

Yes |

Yes |

Mensajeria PP |

|

C’s |

Yes |

? |

- |

|

Podemos |

- |

Yes |

- |

|

VOX |

- |

Yes |

- |

Table 2: use of mobile phone apps to communicate with voters.

Concerns have been raised with the use of WhatsApp for political campaigning, including by political parties, most recently India.

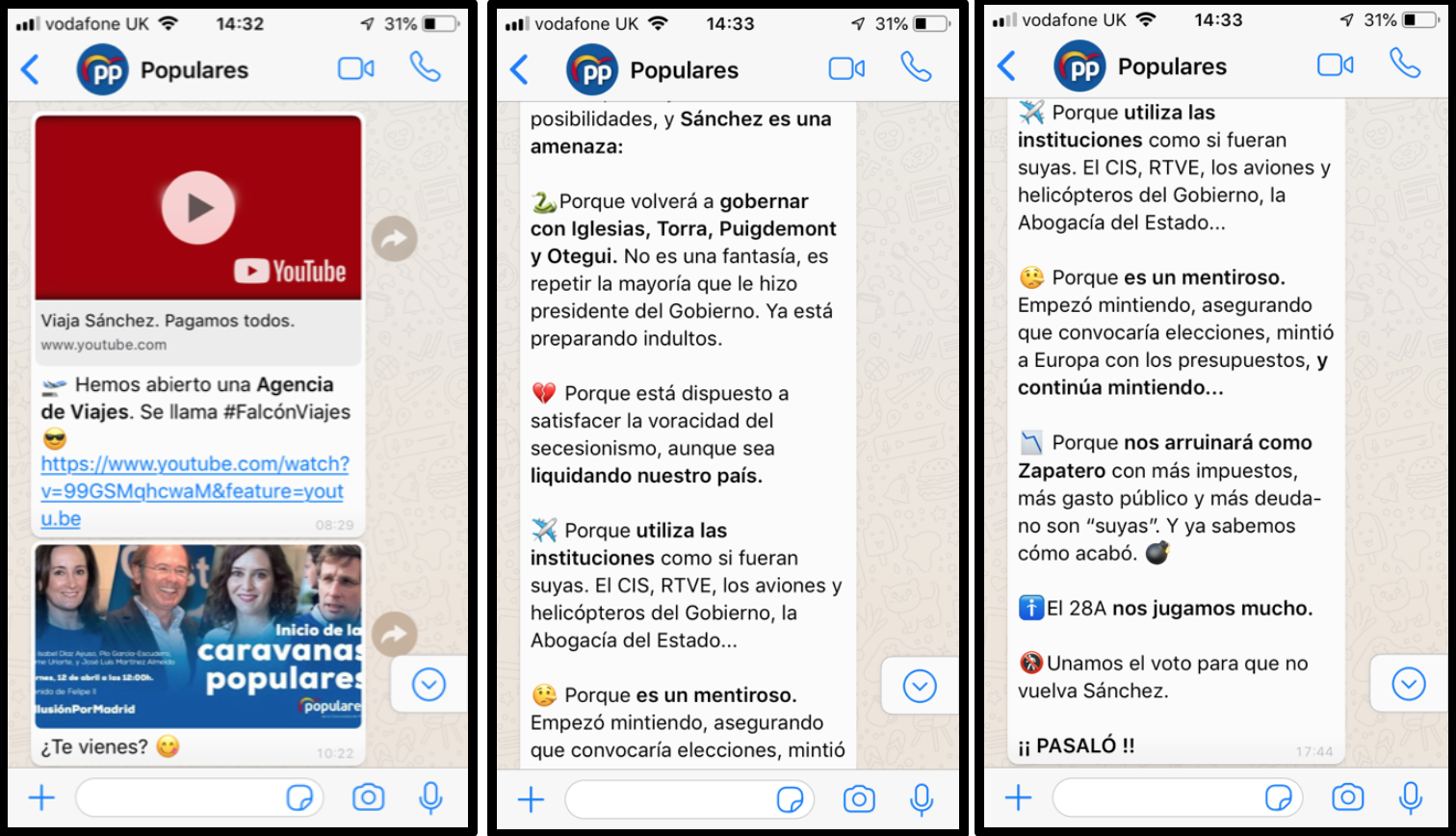

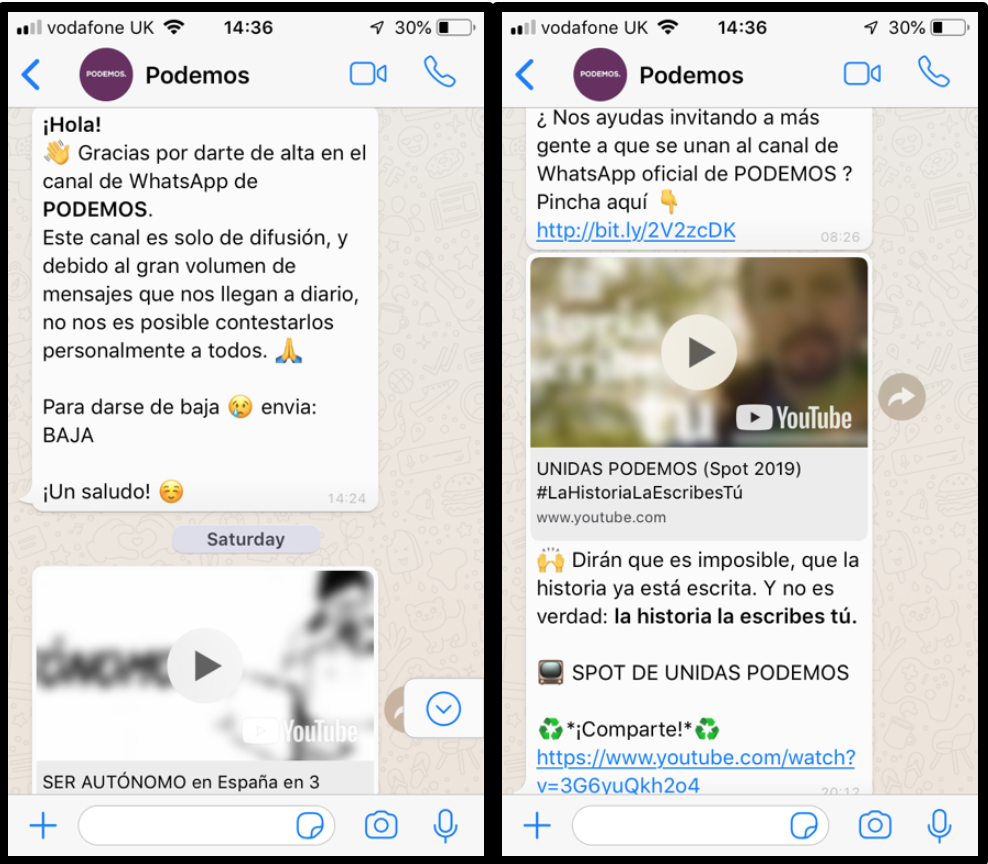

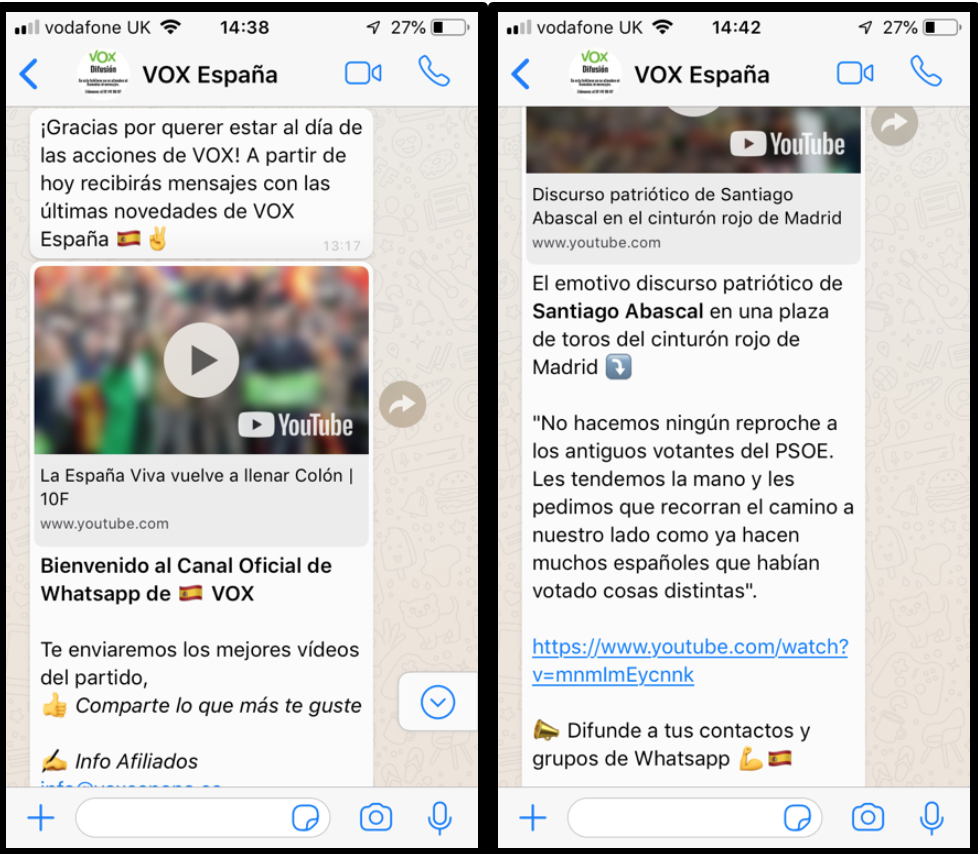

As shown in Table 2, four of the five parties use WhatsApp as a means to communicate with voters and disseminate campaign information. We subscribed to their WhatsApp channels and found two distinct modes of operation: direct personal communication and dissemination of information via broadcast. Even though there are webpages indicating that there is a WhatsApp number that voters can use to communicate with the PSOE party, the links are broken or give a webpage error, thus we did not include them within this analysis.

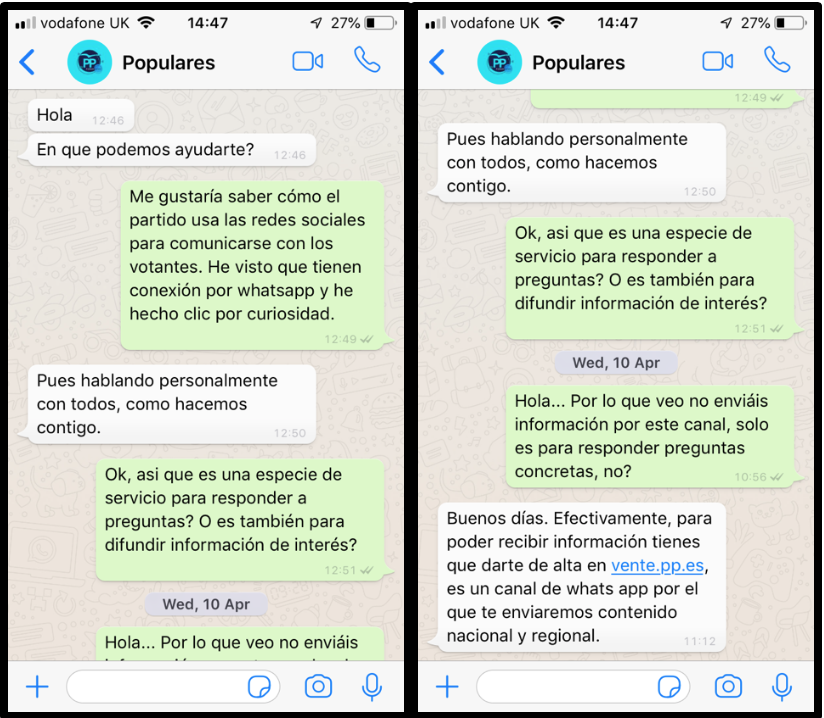

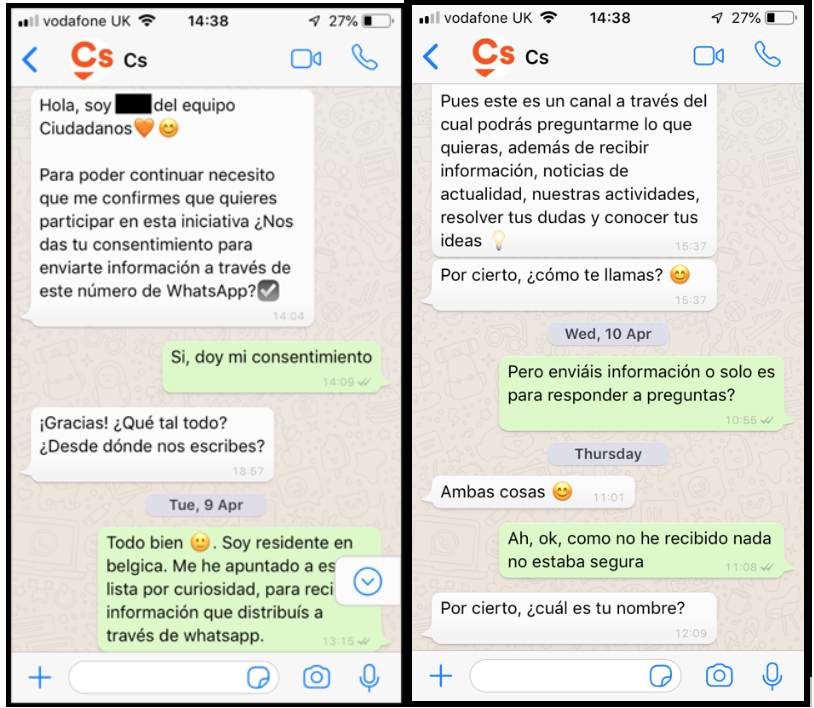

The two parties using WhatsApp as a means of personal communication are PP and Ciudadanos. Upon adding their number and sending an initial message, a person from the party responds.

In the case of PP, the response was a “Hello, how can we help you?” message. We asked about the type of service offered via the channel and they informed us that it was meant to speak personally with voters and answer any questions that they might have. No broadcast information is disseminated via that number. The PP has however a second WhatsApp channel with a different number that is used to broadcast information, tailored to the region of the voter, which is asked during signup.

The welcome message of Ciudadanos included a request for explicit consent in order to continue communication. Once having given consent, the person at the other end continued the conversation with questions involving personal details, such as asking for our location and (insistently) name. Even though they responded to our question about the purpose of the channel saying that it is used to receive broadcast information about their campaign activities, we did not see any such information beyond the personal conversation.

From what we observed, Podemos and VOX use WhatsApp only as a means to broadcast information, with Podemos explicitly indicating in the welcome message that they are not able to follow up on personal messages due to the large volume. PP primarily broadcasts messages with links to YouTube videos that either promote their own candidates or attack their rivals, while the messages we received from VOX and Podemos focused on their own candidates and electoral proposals without mentioning rivals. All three parties encourage their followers to forward the messages to their own contacts.

Party Apps

The use of bespoke apps by political parties, has been flagged in recent campaigns, including in France and Germany.

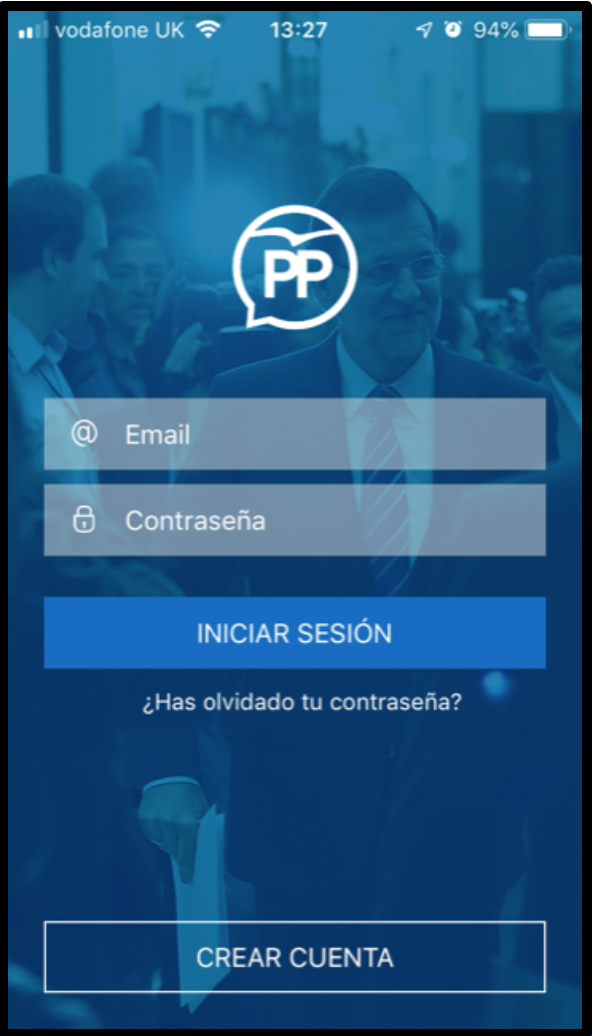

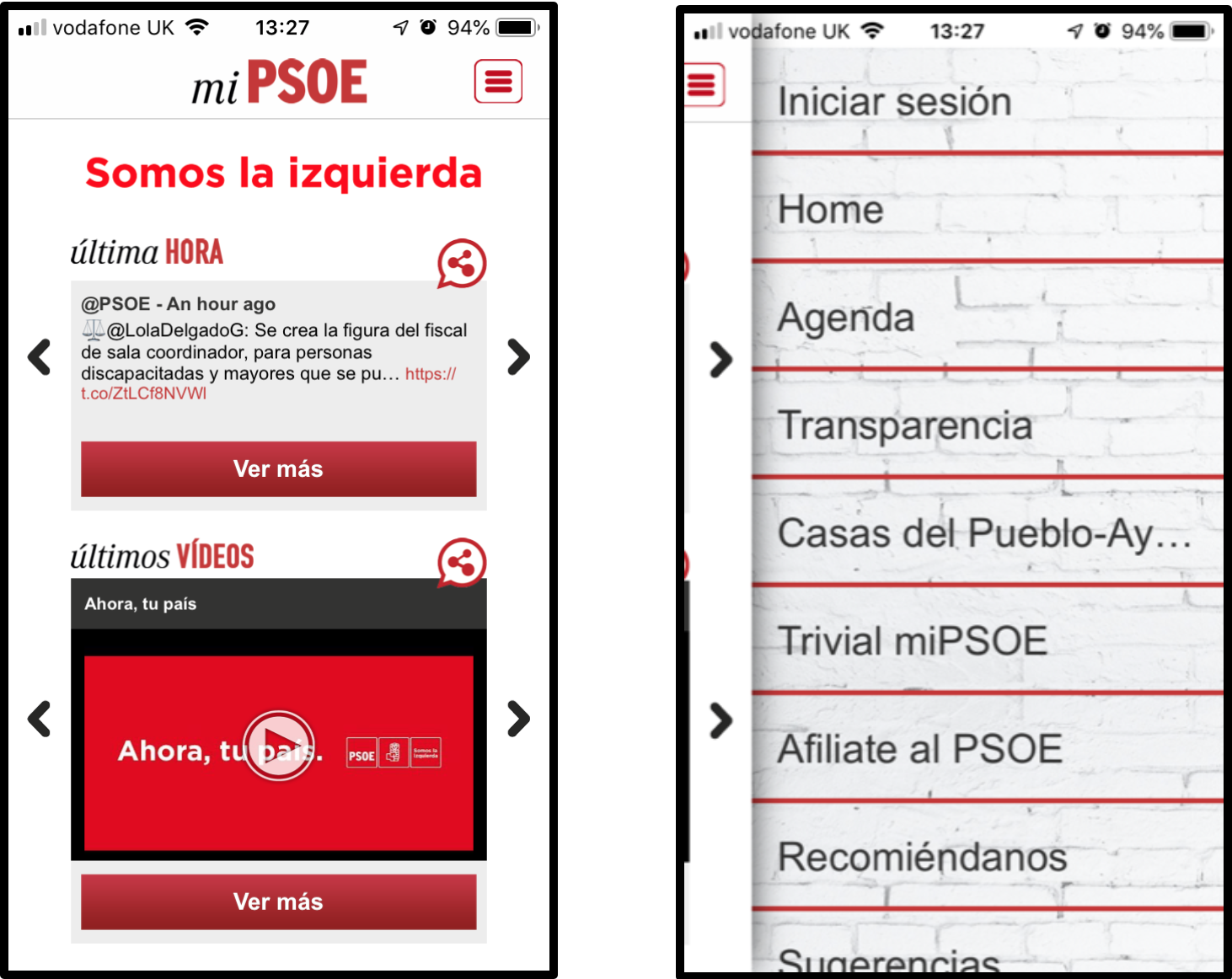

In terms of specific party apps in Spain, as far as we are aware only PSOE and PP have them. The PP app is only usable with an account that requires email registration and appears to be intended for use by party members to coordinate their campaign efforts. The app description indicates that the party needs to approve participation in the app.

The PSOE app is closer to a mobile version of the website and open to non-members. It does not require registration for most of its functionalities, which include accessing information about news, events, party headquarter locations, a trivia game (with e.g., questions about the history of socialism or their political program), and a means to contact the party or send suggestions.

Stated data practices

Besides investigating the parties’ social media engagement, we also checked their claims regarding the processing of personal data (as stated in their privacy and cookie policies), as well as the information they request from individuals that want to register as supporters or members of the party.

The privacy and cookie policies of all five studied parties are disappointingly vague, providing little detail on the sources of data as well as third parties with whom data are shared – despite these being important requirements of the right to information under GDPR.

PSOE’s privacy policy includes open-ended statements mentioning “other companies for mass sending of communications”, companies that perform “statistical, opinion polls or sociological analysis”, and companies that provide “logistics, IT services, call centers” services to the party.

PP’s privacy policy claims that the party is the only recipient of data – while the non-comprehensive cookie policy admits to sharing data with Google and DoubleClick. Information as to the sources of data is also absent.

Ciudadanos states that they use LocalStorage in addition to normal cookies and they name Google, YouTube and DoubleClick as third parties that include cookies in their page. No information is provided about which behavioral data is collected from visitors to the site, how it is processed or with whom it is shared.

Podemos mentions various third parties with whom data is shared, such as banks, tax authorities, election authorities and (unnamed) IT companies that act as data processors. In terms of sources of data, besides saying that users themselves provide information by filling out forms in the website, it mentions “companies that provide internet and telecommunication services” without further specifics.

Finally, VOX’s cookie policy that does not provide much detail. In terms of third parties with whom the data is shared, besides VOX employees and official institutions they open-endedly refer to “others who might also need access to the data” without providing specific names or purposes for the data sharing.

In summary, none of the five parties included in our study provides a detailed list of data sources and third parties with whom they share data. None explicitly mention profiling nor how they use social media to target people. This leaves a number of questions unanswered. For example: Do they purchase commercial datasets from data brokers? Do they link data obtained directly from voters (e.g., via cookies or filled out forms) with data obtained from third parties? Do they use identifiers such as cookies, email or phone number to target and re-target advertising?

What next?

It remains to be seen how each of the parties use of personal data via social media and their wider data practices in the run up to the elections comply with the requirements set out in the AEPD’s circular. Further transparency from the political parties and scrutiny from the AEPD is required if they are to be made a reality.