Electoral advertising, big data and privacy in Peru

The 2020 congressional elections in Peru were different in many ways. For the first time, rules that prohibit parties and candidates from advertising on radio and television through paid ads have been applied.

- In Peru there are no rules that force candidates to be transparent with the spending and advertising guidelines they place on the internet, only general rules for reporting their campaign expenses.

- Unfortunately, almost no Peruvian candidate in the last elections chose to register their advertising as political on Facebook and make their expenses transparent.

This piece was written by PI Partner Hiperderecho's Executive Director Miguel Morachimo and originally appeared here. Image from here.

The recent congressional elections in Peru have been different in many ways. This is primarily because the rules that prohibit parties and candidates from advertising on radio and television through paid ads have been applied for the first time. That has led the effort and expenditure on electoral advertising to be focused on alternative platforms, from printed flyers to websites and social networks. Although these measures sought to “balance” the presence of candidates in the media through advertising, there has been little reflection on how online political advertising works and its shortcomings. Looking ahead to the 2021 election campaign, there are several things happening in this space that deserve special attention.

Around the world, the use of social networks by political actors has been subject to evaluation and change. For example, in 2019 Twitter announced a ban on political ads. For its part, although Facebook does allow this type of advertising on its platforms, in many countries it requires advertisers to comply with special rules. Thus, for example, a political ad in the United States or Brazil will necessarily show the amount spent, the demographic scope of the message, and the identity of the natural or legal person paying it. In addition, such information will be archived for several years in the Facebook’s Ad Library. In the same way, Google also allows political ads ---the publication of political ads under certain rules (eg prohibited remarketing or segmentation by proximity) and also publishes detailed information on advertising spends made by political candidates in the United States, India, and the European Union .

In Peru, however, there are no rules that force candidates to be transparent with the spending and advertising guidelines they place on the internet, only general rules for reporting their campaign expenses. When political advertising was allowed on television and radio, broadcasting companies were required to submit reports to the electoral authority about their income from political content. However, despite the absence of mandatory reporting, companies such as Facebook have made very detailed voluntary transparency tools available to candidates worldwide that allow them to clearly communicate the content, audience, origin and expense in online advertising, which are available in Peru.

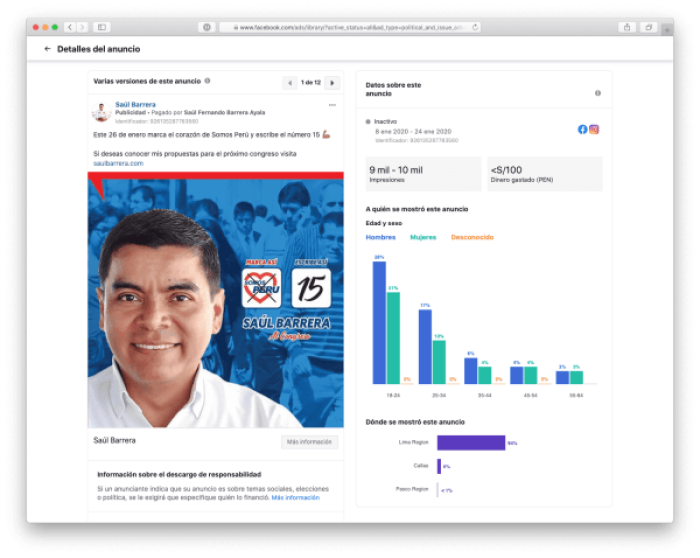

An example of voluntary disclosure.

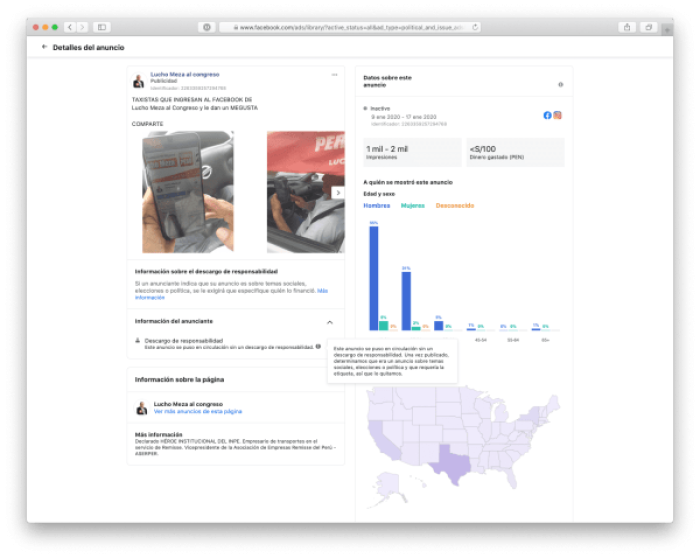

Unfortunately, almost no Peruvian candidate in the last elections chose to register their advertising as political on Facebook and make their expenses transparent. Of the 2325 candidates for Congress who ran last weekend, the only ones who have used Facebook tools to provide information about their political ads were Saúl Barrera (Somos Perú, Lima), Silvia Chucchucan (Somos Perú, Cajamarca), Gerald Cuba (Contigo, Arequipa) and Dennys Cuba (Juntos por el Perú, Junín). A separate case was that of some candidates who, voluntarily or accidentally, targeted their advertising towards Facebook users outside Peru, such as Peruvians abroad. By breaking the transparency rules of countries such as the United States, their advertising was taken out of circulation.

An example of advertising detected and removed by Facebook because it was targeted to users outside Peru.

Having more information on how candidates advertise online is not only important for monitoring campaign expenses. Unlike advertising through other means, doing it on the internet involves specifically defining the audience to which you want to direct your messages: where they live, how old they are, what they like, or what groups they belong to. This is something that many candidates could deduce or approximate through opinion polls and focus groups. But in our country, this is also facilitated by the Organic Law of Elections, which since its approval in 1997 grants political parties, independent groups and alliances the right to receive a complete copy of the voter registry of their district, city or of the entire country from RENIEC.

Normally, the electoral roll includes many personal data about people, such as names and surnames, unique identification code of those registered, photographs, digitized signatures, district, province and department, as well polling station number and declaration of disability. The only information that is part of the Register but is not considered public or delivered to the parties is the voters’ address and fingerprints, thanks to a 2016 amendment to the Organic Law of Elections. This change was confirmed recently by the General Directorate of Data Protection, the Peruvian authority on the protection of personal data, in response to a query made by the National Jury of Elections.

In June 2018, the same General Directorate for Data Protection decided on how and for what purposes political parties should use the information of the register. In a nutshell, it noted that it should only be used to verify errors such as the inclusion of deceased citizens, those enrolled more than once, or those who are disqualified from voting. Although the Law itself does not establish limitations or conditions for parties to use this information, the Data Protection Authority derives these rules from the general principles of the Data Protection Law. A few weeks ago, Hiperderecho contacted RENIEC directly to find out what data was delivered to the parties, in what format, and to whom it had been recently delivered. They responded that the Register sent to the parties included information on the voters’ names, surnames, ID number, district, province, department and polling station. This information is freely given to all political parties with valid registration before the National Election Jury in a sealed envelope CD, in PDF format and in a password file. In fact, RENIEC itself has devoted a section of its website to list the parties that have requested this information since 2014. More than a few have obtained this information year after year, even outside election periods.

What could a party do with the digitized information of the Electoral Register? For a marketing or data specialist, an authentic database of this type and size can be a very powerful campaign tool. It could be combined with other commercially or publicly available databases, such as those of the census or of the risk centers, and begin to generate types of voters, understand their sensitivities, determine their socio-economic profile and, based on these findings, create advertising that was only visible to young women in Arequipa, for business owners in Piura, or for high school students in Huancayo. It could also be cross referenced with information already available on social networks or internet profiles and identify common patterns among voters that serve to create publicity targeted to those groups. Since it is very difficult to keep track of information once it is shared, we do not have a mechanism to ensure that the parties are not exploiting this information for their interests and using it beyond the purposes indicated by the electoral legislation. All we can do is report when that information has already been exploited, if we can detect it.

In this scenario, the use of advertising transparency tools such as those of Facebook is more relevant than ever: it allows us to understand which messages the candidates choose to advertise, to which audiences in terms of gender, age, and location, and how much they spend to do so. We do not know if Peruvian politics have already entered the big data era and the exploitation of personal data, but unfortunately there seem to be conditions for this to happen soon.