New Privacy International report reveals dangerous lack of oversight of secret global surveillance networks

A major new report published today by Privacy International has identified alarming weaknesses in the oversight arrangements that are supposed to govern the sharing of intelligence between state intelligence agencies.

'Secret Global Surveillance Networks: Intelligence Sharing Between Governments and the Need for Safeguards' is based on an international collaborative investigation carried out by 40 NGOs in 42 countries.

Previously undisclosed documents obtained by PI via litigation in the US under Freedom of Information laws shed further light on the ‘Five Eyes’ surveillance network. The documents reveal that the US conducts surveillance while based in secret facilities in partner countries, parts of which are not even accessible to the host countries' own governments - including their oversight bodies. They further reveal that Five Eyes sharing arrangements were amended and enhanced throughout the 2000s.

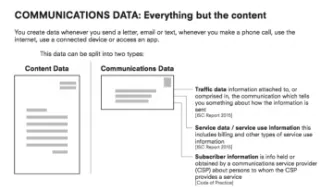

Intelligence sharing has evolved dramatically with the rise of new surveillance technologies, enabling multiple governments to collect, store and share vast troves of personal information, including data collected via mass surveillance techniques.

It is essential that appropriate legal safeguards and oversight mechanisms exist to regulate these practices. Safeguards designed in the era of phone wiretapping cannot be used in the era of mass surveillance, where governments are increasingly collecting enormous amounts of digital information on many people, including people of no interest to the intelligence agencies. The secrecy shrouding intelligence sharing practices and arrangements cannot continue.

Secret surveillance networks

Governments share intelligence in various ways. Pursuant to an intelligence sharing arrangement, a government might, amongst other things:

· Access “raw” (i.e. unanalysed) information, such as internet traffic intercepted in bulk from fibre optic cables by another government;

· Access information stored in databases held by another government or jointly managed with another government;

· Receive the results of another government’s analysis of information, for example, in the form of an intelligence report.

In September 2017, Privacy International – in partnership with 40 national civil society organisations – wrote to oversight bodies in 42 countries as part of a project to increase transparency around intelligence sharing and to encourage oversight bodies to scrutinise the law and practice of intelligence sharing in their respective countries. Over the past few months, we have received responses from oversight bodies in 21 countries.

PI's research and the responses reveal that:

• Most countries around the world lack domestic legislation to regulate intelligence sharing. Based on our research, only one country has introduced specific legislation to explicitly regulate intelligence sharing;

• Oversight bodies in nine out of 21 countries responded that intelligence agencies have no clear legal obligation to inform them of the intelligence sharing arrangements into which they enter. Only the oversight body of one country indicated that the intelligence agencies are required by law to provide them access to intelligence sharing arrangements.

• Oversight bodies in nine out of 21 countries responded that they have full or broad access to information about intelligence sharing activities. One oversight body indicated that it was prohibited from accessing such information and several others left ambiguous the level of access that they have.

• None of the oversight bodies indicated that they have powers to authorise decisions to share intelligence, either at a general level, or in specific circumstances. In many of those countries, the process to authorise intelligence sharing appears to bypass any independent authority.

The findings have significant implications for human rights. As discussed in the report, intelligence sharing constitutes an interference with the right to privacy and must therefore be subject to safeguards well-established in international human rights law, including adequate oversight. Without appropriate safeguards, states can use intelligence sharing as a way to outsource surveillance, bypassing domestic constraints on their surveillance activities. Unregulated intelligence sharing can also contribute to or facilitate serious human rights abuses, such as unlawful arrest or detention, or torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

In the report, PI makes a series of urgent recommendations to legislative bodies, executives, intelligence agencies, and oversight bodies, and calls for the establishment, through primary legislation, of publicly accessible legal frameworks governing intelligence sharing, and for increased powers for oversight bodies to ensure intelligence sharing arrangements comply with international and domestic law.

New Disclosures

In December 2017, in response to PI litigation, the US State Department disclosed records relating to Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap. Pine Gap is a base located in Alice Springs in Australia and is jointly operated by the US and Australia. From Pine Gap, the US controls satellites across several continents, which can conduct surveillance of wireless communications, like those transmitted via mobile phones, radios and satellite uplinks. The intelligence gathered supports both intelligence activities and military operations, including drone strikes. The disclosure includes what appears to be a 1985 State Department cable, which summarises public reporting and discussion of Pine Gap, including a handwritten note confirming that there was an area of the facility where Australian nationals are not permitted entry.

The State Department also disclosed records suggesting that the intelligence sharing agreement between the Five Eyes (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the US) was amended and enhanced in the 2000s, although the details of any such agreement remain firmly outside of public view and public scrutiny.

The NSA also disclosed new appendices to the intelligence sharing agreement between the Five Eyes. These records date from 1959-61 and update our understanding of the agreement by several years but nonetheless remain decades out of date.

Our report comes following a 2017 YouGov poll commissioned by Privacy International about intelligence sharing arrangements between the UK and US, which found that 78% of Britons think Trump will use his surveillance powers for personal gain, with over half having no trust (54%) that Trump will only use surveillance for legitimate purposes. It also found that 73% of Britons think the UK government should explain what safeguards exist against Donald Trump misusing data about British people.